by Barbara Fischkin

Eight weeks have passed since I wrote about my Cousin Bernie—and how, posthumously, he adds to my own memories of him. As readers may remember from my last offering, Cousin Bernie’s widow, Joan Hamilton Morris, sent me the pages of an incomplete memoir her late husband pecked out on a vintage typewriter in an adult education class he took after retiring as a university professor of psychology and mathematics.

If Cousin Bernie were alive today he would be 102. Those pages of memoir chapters, some more worn than others, remain in a place of honor, tucked into a corner of my own writing table. I feel that “Cousin Joanie,” as I call his widow, sent them to me for safekeeping—and for presentation to the world. Originally I thought I could do this in one or two chapters. A deeper read has revealed a surprising amount of insight. Here is my fourth take on my cousin, who fascinates me despite his evergreen persona as a nerdy, chubby, lost boy from Brooklyn. There will be a fifth offering and probably a sixth. If it seems Bernie is taking over my memoir, I am fine with this. I have written a lot about my mother’s side of the family. Now it is my father’s family’s turn. And what better way to bring them into the light, than through Cousin Bernie?

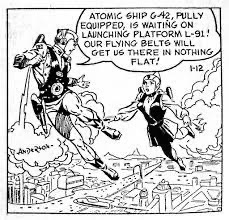

What follows is Cousin Bernie, Part Four. I’ve only edited it slightly, less so I think than his Adult Education teacher. So far, my minor editing has provoked no lightning bolts from the heavens. I have discovered another Bernie, a child who believed he could fly like his comic strip hero.

“I was eight years old, and my sister, Gertie, six. We had just been transplanted to Bridgeport, Connecticut from Brooklyn, New York. My father, a home painter and decorator, felt that he could do better in terms of finding work in a smaller city.

“Here, a whole new set of stimuli presented itself: A Benjamin Franklin stove in the kitchen, a gas water heater in the bathroom, which had to be lighted so we could bathe, and a coal bin on the back porch. There was a scuttle for bringing in coal for the stove. The Saturday Sabbath meal preparations—gefilte fish, stewed chicken and beef, challahs, cookies and pies—began as early as Wednesday night. The stove was banked and allowed to go out on Saturday night.

“We slept as the stove died down and, on Sunday mornings, my sister and I would climb into my parents’ big bed. Pop got up wearing his union suit, put on a robe, removed the ashes, kindled a new fire in the stove and came back to bed with us for my reading of the Sunday comics. My sister, Gertie, pointed to each speech bubble, as I read them. It seemed to me that Andy Gump’s nose or chin was strange looking. I disliked it when the bubbles were long. But it was here in the Sunday comics that I encountered the adventures of ‘Buck Rodgers in the Twenty-Fifth Century.’ Read more »

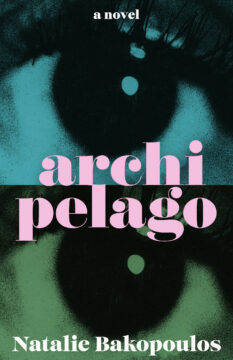

Natalie Bakopoulos: Thank you so much, Philip, for starting this conversation, and for these wonderful observations and connections. You’re absolutely right, I was indeed playing with the idea of “beginnings.” “Here in Greece,” the narrator says, “the rivers rarely have a single source: They spring from the mountains at several places.” I also wanted to think about the arbitrariness of origin and a way of thinking about belonging that wasn’t necessarily about “roots”—but instead rhizomes, as Edouard Glissant, and others, might say.

Natalie Bakopoulos: Thank you so much, Philip, for starting this conversation, and for these wonderful observations and connections. You’re absolutely right, I was indeed playing with the idea of “beginnings.” “Here in Greece,” the narrator says, “the rivers rarely have a single source: They spring from the mountains at several places.” I also wanted to think about the arbitrariness of origin and a way of thinking about belonging that wasn’t necessarily about “roots”—but instead rhizomes, as Edouard Glissant, and others, might say.

The wealthy and powerful have always used the narrative to their advantage. The narrative defines them as superior in some way, and thus deserving of their power and wealth. In ancient times, they might be descended from the Gods, or at least favored by them or otherwise connected to them, perhaps through special communicative powers that granted them insights into the will of the Gods or God. In modern capitalist societies, that narrative promotes a fantasy of merit. You are rich and/or powerful because you are better. You are more civilized, better educated, more intelligent, or blessed with an exceptional work ethic. These narratives cast wealth and/or power as not only justifiable, but deserved.

The wealthy and powerful have always used the narrative to their advantage. The narrative defines them as superior in some way, and thus deserving of their power and wealth. In ancient times, they might be descended from the Gods, or at least favored by them or otherwise connected to them, perhaps through special communicative powers that granted them insights into the will of the Gods or God. In modern capitalist societies, that narrative promotes a fantasy of merit. You are rich and/or powerful because you are better. You are more civilized, better educated, more intelligent, or blessed with an exceptional work ethic. These narratives cast wealth and/or power as not only justifiable, but deserved.

In

In

In a recent essay,

In a recent essay,

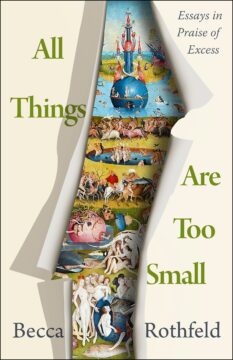

We’re living at a time when the glorification of independence and individualism is harming the world and others in it, as well as leading to an epidemic of loneliness. According to Jay Garfield, the root of suffering is in our self-alienation, and one symptom of our alienation is clinging to the notion that we are selves. “We are wired to misunderstand our own mode of existence,” he writes in his brief yet substantial 2022 book,

We’re living at a time when the glorification of independence and individualism is harming the world and others in it, as well as leading to an epidemic of loneliness. According to Jay Garfield, the root of suffering is in our self-alienation, and one symptom of our alienation is clinging to the notion that we are selves. “We are wired to misunderstand our own mode of existence,” he writes in his brief yet substantial 2022 book,

Uuriintuya Dagvasambuu (Mongolia). Woman in Ulaanbaatar: Dreams Carried by Wind, 2025.

Uuriintuya Dagvasambuu (Mongolia). Woman in Ulaanbaatar: Dreams Carried by Wind, 2025.