by Herbert Harris

I began my psychiatric training in 1990, the year that marked the start of a program called the “Decade of the Brain.” This was a well-funded, high-profile initiative to promote neuroscience research, and it succeeded spectacularly. New imaging techniques, molecular insights, and psychopharmacological discoveries transformed psychiatry into a vibrant biomedical science. The program brought thousands of careers, including my own, into the neurosciences.

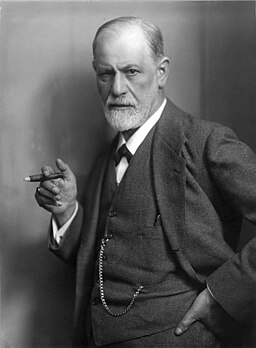

Despite its progress, the Decade of the Brain also widened an existing rift. This was the large gap between the psychoanalytic tradition and the biological sciences. The divide wasn’t new. Freud started with neurology but shifted to psychoanalysis when the brain sciences of his time couldn’t fully explain the complexities of the mind. For the first half of the 20th century, psychoanalysis was the main way to understand mental illness. Then, in the 1950s, new psychiatric drugs appeared: chlorpromazine for psychosis, lithium for mood disorders, and antidepressants for depression. For the first time, it seemed possible to treat mental illness by directly targeting the brain, rather than long-term therapy or institutional care.

By the time I was a resident, these diverging traditions had opened into a chasm. On one side was biological psychiatry, focused on neurotransmitters, neuroimaging, and cognitive-behavioral treatments, with outcomes that could be measured and tested. On the other side were psychoanalysis and its branches: attachment theory, object relations, and the investigation of unconscious conflicts through language, narrative, and symbolism. They had become separate languages, spoken within distinct professional communities, each wary of the other. There were occasional efforts at rapprochement, but little sustainable progress. By the end of the Decade of the Brain, reconciliation seemed almost impossible. I was fortunate to be in a training program that had a research track, allowing me to work in a lab, but I also had mentors who were distinguished analysts. It was like being in two different residencies.

Both have proven valuable over the years, but I never expected them to converge. However, today, circumstances appear to be shifting. A merging of neurobiology, computational neuroscience, and neuroimaging has created a new paradigm: active inference. For the first time, we can start to identify strong links between analytic models of the mind and biological models of the brain. Read more »

I moved to Berlin in 1984, but have rarely written about my experiences living in a foreign country; now that I think about it, it occurs to me that I lived here as though in exile those first few years, or rather as though I’d been banished, as though it hadn’t been my own free will to leave New York. It’s difficult to speak of the time before the Wall fell without falling into cliché—difficult to talk about the perception non-Germans had of the city, for decades, because in spite of the fascination Berlin inspired, it was steeped in the memory of industrialized murder and lingering fear and provoked a loathing that was, for some, quite visceral. Most of my earliest friends were foreigners, like myself; our fathers had served in World War II and were uncomfortable that their children had wound up in former enemy territory, but my Israeli and other Jewish friends had done the unthinkable: they’d moved to the land that had nearly extinguished them, learned to speak in the harsh consonants of the dreaded language, and betrayed their family and its unspeakable sufferings, or so their parents claimed. We were drawn to the stark reality of a walled-in, heavily guarded political enclave, long before the reunited German capital became an international magnet for start-ups and so-called creatives. We were the generation that had to justify itself for being here. It was hard not to be haunted by the city’s past, not to wonder how much of the human insanity that had taken place here was somehow imbedded in the soil—or if place is a thing entirely indifferent to us, the Earth entirely indifferent to the blood spilled on its battlegrounds.

I moved to Berlin in 1984, but have rarely written about my experiences living in a foreign country; now that I think about it, it occurs to me that I lived here as though in exile those first few years, or rather as though I’d been banished, as though it hadn’t been my own free will to leave New York. It’s difficult to speak of the time before the Wall fell without falling into cliché—difficult to talk about the perception non-Germans had of the city, for decades, because in spite of the fascination Berlin inspired, it was steeped in the memory of industrialized murder and lingering fear and provoked a loathing that was, for some, quite visceral. Most of my earliest friends were foreigners, like myself; our fathers had served in World War II and were uncomfortable that their children had wound up in former enemy territory, but my Israeli and other Jewish friends had done the unthinkable: they’d moved to the land that had nearly extinguished them, learned to speak in the harsh consonants of the dreaded language, and betrayed their family and its unspeakable sufferings, or so their parents claimed. We were drawn to the stark reality of a walled-in, heavily guarded political enclave, long before the reunited German capital became an international magnet for start-ups and so-called creatives. We were the generation that had to justify itself for being here. It was hard not to be haunted by the city’s past, not to wonder how much of the human insanity that had taken place here was somehow imbedded in the soil—or if place is a thing entirely indifferent to us, the Earth entirely indifferent to the blood spilled on its battlegrounds.