by Herbert Harris

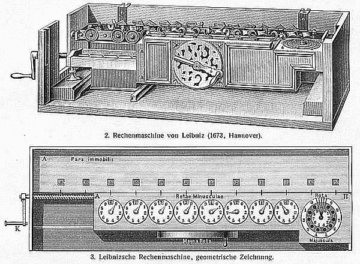

Is mathematics created or discovered? For over two thousand years, that question has puzzled philosophers and mathematicians alike. In Plato’s Meno, Socrates encourages an uneducated boy to “discover” a geometrical truth simply by answering a series of guided questions. To Plato, this demonstrated that mathematical knowledge is innate, that the soul recalls truths it has always known. The intuitionists of the early twentieth century, however, rejected this idea of eternal forms. For thinkers like Poincaré and Brouwer, mathematics was not revelation but construction: an activity of the human mind unfolding in time.

The debate continues today in an unexpected new arena. As artificial intelligences start to generate proofs, conjectures, and even entire branches of formal reasoning, we are prompted to ask again: what does it mean to do mathematics? Current systems excel at symbol manipulation and pattern matching, but are they truly thinking in any meaningful way, or just rearranging signs? The deeper question is how humans do mathematics. What happens in the brain when a mathematician recognizes a pattern, intuitively sees a relation, or invents a new kind of number?

In what follows, I’ll trace that question from ancient philosophy to modern neuroscience and then to the newest foundations of mathematics. We’ll see that mathematical invention may be the natural expression of the brain’s recursive, embodied intelligence, and that this perspective could transform how we think about both mathematics and AI. Read more »

Barring that reality, and knowing this would be an ongoing, lifelong issue, I got a tattoo on my Visa-paying forearm to remind myself that my actions affect the entire world. I borrowed Matisse’s

Barring that reality, and knowing this would be an ongoing, lifelong issue, I got a tattoo on my Visa-paying forearm to remind myself that my actions affect the entire world. I borrowed Matisse’s