by Gary Borjesson

It is the first week of the new year, a time traditionally given to reflecting on the year past and the year to come. Reviewing, summing things up—all those top 10 lists—and making resolutions. Having slowly gained more knowledge of what is stable in my disposition (for better and worse), I’m less tempted to dream of radical reinvention or even self-improvement. Depending on my mood, this can feel like self-acceptance or defeat.

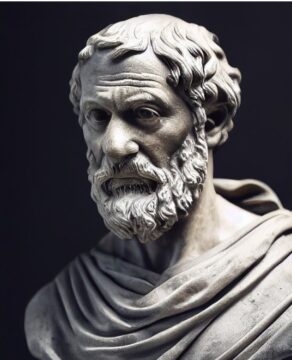

One way of describing the situation is to say that I’m getting to know what Carl Jung described as the archetypal aspects of my psyche. Jung acknowledged that his account is a paraphrase of Plato’s description of the psychic patterns that structure our experience. For Jung these emerge from the collective unconscious, a realm beyond immediate conscious awareness. Plato’s Socrates locates them in an analogous place, the Underworld. These archetypes guide our lives in some respects, but they’re not the only forces at work. For Socrates and Jung, we exercise our power to be truly self-determining through getting to know the patterns that guide our lives, but do not determine our fates.

In honor of the birth of a new year, I want to share the story Socrates tells at the end of the Republic, about how souls come to choose the lives into which they’ll be reborn. For those familiar with depth psychology, this myth of Er (as the story is called) will be strikingly resonant.

A friend once told me he’d spent years trying to make himself into a scholar, and by the world’s eyes he had succeeded. But it never felt like a fit to him. Eventually he realized that, whatever his conscious intentions, he had the instincts and desires of an artist. (His academic articles kept wanting to become stories!) Denying this part of himself had generated internal conflict. So, rather than work against his natural wiring, he started finding ways to be an artist in his work and life. Read more »

We’re living at a time when the glorification of independence and individualism is harming the world and others in it, as well as leading to an epidemic of loneliness. According to Jay Garfield, the root of suffering is in our self-alienation, and one symptom of our alienation is clinging to the notion that we are selves. “We are wired to misunderstand our own mode of existence,” he writes in his brief yet substantial 2022 book,

We’re living at a time when the glorification of independence and individualism is harming the world and others in it, as well as leading to an epidemic of loneliness. According to Jay Garfield, the root of suffering is in our self-alienation, and one symptom of our alienation is clinging to the notion that we are selves. “We are wired to misunderstand our own mode of existence,” he writes in his brief yet substantial 2022 book,  In my last

In my last

I have a confession to make: I ❤️ Seymour Glass. If you don’t know who that is, count yourself lucky and walk away now—come back in a few weeks when I’ll be discussing humiliating experiences at middle-school dances or whatever. (Obviously I am joking—as always, I desperately want you to finish reading this essay.)

I have a confession to make: I ❤️ Seymour Glass. If you don’t know who that is, count yourself lucky and walk away now—come back in a few weeks when I’ll be discussing humiliating experiences at middle-school dances or whatever. (Obviously I am joking—as always, I desperately want you to finish reading this essay.) Now that the hangover from New Year’s Eve is abating for many, and we might be freshly open to some self-improvement, consider a Buddhist view of using meditation to tackle addictions. I don’t just mean for substance abuse, but also for that incessant drive to check social media just once more before starting our day or before we finally lull ourselves to sleep by the light of our devices, or the drive to buy the store out of chocolates at boxing day sales. Not that there’s anything wrong with that on its own– it’s a sale after all–but when actions are compulsive instead of intentional, then this can be a different way of approaching the problem from the typical route. I’m not a mental health professional, but this is something I’ve finally tried with earnest and found helpful, but it took a very different understanding of it all to get just this far (which is still pretty far from where I’d like to be).

Now that the hangover from New Year’s Eve is abating for many, and we might be freshly open to some self-improvement, consider a Buddhist view of using meditation to tackle addictions. I don’t just mean for substance abuse, but also for that incessant drive to check social media just once more before starting our day or before we finally lull ourselves to sleep by the light of our devices, or the drive to buy the store out of chocolates at boxing day sales. Not that there’s anything wrong with that on its own– it’s a sale after all–but when actions are compulsive instead of intentional, then this can be a different way of approaching the problem from the typical route. I’m not a mental health professional, but this is something I’ve finally tried with earnest and found helpful, but it took a very different understanding of it all to get just this far (which is still pretty far from where I’d like to be).