by Mark R. DeLong

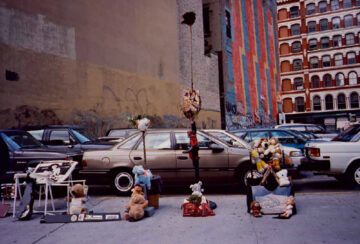

In January five years ago, amidst the turmoil and isolation of a world pandemic, I decided it was time to do a month-long art project. I was newly “retired” (a word that I then disdained and avoided using), and I was intrigued by a project that poet Bernadette Mayer took on when she was in her twenties and living in New York. In July 1971, she took up her 35 mm camera and exposed a 36-shot roll of film every day, processing the film at night, and through it all wrote daily in her free poetic prose. She called her project Memory and it became a gallery exhibition at 98 Greene Street in February 1972—all 1,116 photos with more than six hours of audio narration. In May 2020, nearly fifty years after young Bernadette took her photographs and wrote her words, Memory was issued in book form by Siglio Press.

I wondered whether Memory could serve as a model or at least an inspiration for a project in January 2021. I had my doubts for many reasons, and I knew that having the energy of a twenty-year-old was useful for Mayer back in 1971. My reservations notwithstanding, I decided to apply the “Memory Model” for project I named “Second Act—Re:Tooling.” Maybe I could “use the disciplined, thirty-six exposure method to lay open some matters that might otherwise be obscured from ‘normal’ sight of the everyday,” I wrote a couple days before launch. “I wanted the photography and the writing to, well, focus and direct attentions to new and lurking realities of my new situation.”

It was a good month-long project but not a work of art by any measure, and I rarely achieved thirty-six digital photos in a day—a fact that surprised me a little, given how little effort my digital cameras required. From the first, I treated the month of writing and photo-taking as a data gathering effort—useful in the future perhaps—but not nearly “fully cooked” when the project ended on January 31, 2021. Read more »

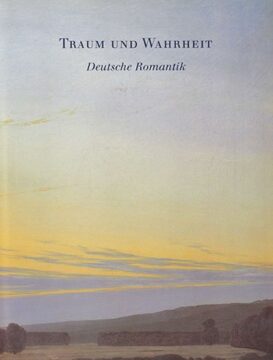

The first time I became aware of Friedrich, many years ago, I was in Zurich to meet an elderly Jungian psychoanalyst—my head stuffed with theoretical questions and eerie dreams with soundtracks by Scriabin. Walking down the Bahnhofstrasse, I passed a bookstore window displaying a stunning art book with the elegant title Traum und Wahrheit (Dream and Truth) and a simple subtitle: Deutsche Romantik. I didn’t yet speak German, but I knew enough to be interested. The book was too heavy for my luggage. I bought it anyway and had it shipped.

The first time I became aware of Friedrich, many years ago, I was in Zurich to meet an elderly Jungian psychoanalyst—my head stuffed with theoretical questions and eerie dreams with soundtracks by Scriabin. Walking down the Bahnhofstrasse, I passed a bookstore window displaying a stunning art book with the elegant title Traum und Wahrheit (Dream and Truth) and a simple subtitle: Deutsche Romantik. I didn’t yet speak German, but I knew enough to be interested. The book was too heavy for my luggage. I bought it anyway and had it shipped. What lured my eye to the cover as I passed by was a partial view from one of my now favorite Friedrich paintings, Das Große Gehege (The Great Enclosure)—a cool marshy landscape evoking real ones I would later see from train windows. How could just a corner of a painting have such power? It was the light, the late afternoon saturation of yellow, the black shadowed trees, and the hint of evening gloom already visible as gray on the horizon even though the sky above was still blue. I was captivated.

What lured my eye to the cover as I passed by was a partial view from one of my now favorite Friedrich paintings, Das Große Gehege (The Great Enclosure)—a cool marshy landscape evoking real ones I would later see from train windows. How could just a corner of a painting have such power? It was the light, the late afternoon saturation of yellow, the black shadowed trees, and the hint of evening gloom already visible as gray on the horizon even though the sky above was still blue. I was captivated.

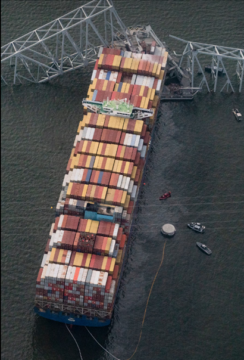

One of nature’s most endearing parlor tricks is the ripple effect. Drop a pebble into a lake and little waves will move out in concentric circles from the point of entry. It’s fun to watch, and lovely too, delivering a tiny aesthetic punch every time we see it. It’s also the well-worn metaphor for a certain kind of cause-and-effect, in which the effect part just keeps going and going. This metaphor is a perfect fit for one of the worst allisions in US maritime history, leading to the collapse of Baltimore’s Francis Scott Key Bridge after it was hit by the container ship MV Dali on the morning of March 26, 2024.

One of nature’s most endearing parlor tricks is the ripple effect. Drop a pebble into a lake and little waves will move out in concentric circles from the point of entry. It’s fun to watch, and lovely too, delivering a tiny aesthetic punch every time we see it. It’s also the well-worn metaphor for a certain kind of cause-and-effect, in which the effect part just keeps going and going. This metaphor is a perfect fit for one of the worst allisions in US maritime history, leading to the collapse of Baltimore’s Francis Scott Key Bridge after it was hit by the container ship MV Dali on the morning of March 26, 2024.

Consider again the wooden desk. It was once part of a tree, like the ones outside your window. It became a bit of furniture though a long process of growth, cutting, shaping buying and selling until it got to you. You sit before it as it has a use – a use value – but it was made, not to give you a platform for your coffee or laptop, but in order to make a profit: it has an exchange value, and so had a price. It is a commodity, the product of an entire economic system, capitalism, that got it to you. Someone laboured to make it and someone else, probably, profited by its sale. It has a history, a backstory.

Consider again the wooden desk. It was once part of a tree, like the ones outside your window. It became a bit of furniture though a long process of growth, cutting, shaping buying and selling until it got to you. You sit before it as it has a use – a use value – but it was made, not to give you a platform for your coffee or laptop, but in order to make a profit: it has an exchange value, and so had a price. It is a commodity, the product of an entire economic system, capitalism, that got it to you. Someone laboured to make it and someone else, probably, profited by its sale. It has a history, a backstory. All of this is the case, but none of it simply appears to the senses. Capitalism itself isn’t a thing, but that doesn’t make it less real. The idea that all that there really is amounts to things you can bump into or drop on your foot is the ‘common sense’ that operates as the ideology of everyday life: “this is your world and these are the facts”. But really, nothing is like that: there are no isolated facts, but rather a complex, twisted web of mediations: connections and negations that transform over time.

All of this is the case, but none of it simply appears to the senses. Capitalism itself isn’t a thing, but that doesn’t make it less real. The idea that all that there really is amounts to things you can bump into or drop on your foot is the ‘common sense’ that operates as the ideology of everyday life: “this is your world and these are the facts”. But really, nothing is like that: there are no isolated facts, but rather a complex, twisted web of mediations: connections and negations that transform over time.

A cinematographer would recognize this as a crane shot, or its replacement, the drone shot. This crane or drone doesn’t move. It defines the POV (point of view) of the painter, and shows how far his perspective can reach and how much he can cram into the in-between, that 2D surface which expands vertically with every higher angle of his POV, as in this crane shot from Gone with the Wind.

A cinematographer would recognize this as a crane shot, or its replacement, the drone shot. This crane or drone doesn’t move. It defines the POV (point of view) of the painter, and shows how far his perspective can reach and how much he can cram into the in-between, that 2D surface which expands vertically with every higher angle of his POV, as in this crane shot from Gone with the Wind.

They all want it: the ‘digital economy’ runs on it, extracting it, buying and selling our attention. We are solicited to click and scroll in order to satisfy fleeting interests, anticipations of brief pleasures, information to retain or forget. Information: streams of data, images, chat: not knowledge, which is something shaped to a human purpose. They gather it, we lose it, dispersed across platforms and screens through the day and far into the night. The nervous system, bombarded by stimuli, begins to experience the stressful day and night as one long flickering all-consuming series of virtual non events.

They all want it: the ‘digital economy’ runs on it, extracting it, buying and selling our attention. We are solicited to click and scroll in order to satisfy fleeting interests, anticipations of brief pleasures, information to retain or forget. Information: streams of data, images, chat: not knowledge, which is something shaped to a human purpose. They gather it, we lose it, dispersed across platforms and screens through the day and far into the night. The nervous system, bombarded by stimuli, begins to experience the stressful day and night as one long flickering all-consuming series of virtual non events.