by Ashutosh Jogalekar

In every generation, young people find causes to champion. Today’s students rally against wars in foreign lands, the environmental record of large companies, the entanglement of Silicon Valley with the Pentagon and China, or the human rights policies of nations like China. These are important causes. In a free country like the United States, protest is not only permitted but celebrated as part of our civic DNA. In fact in a democracy it’s essential: one only has to think of how many petitions and protests were undertaken by women suffragists, by the temperance and the labor movements and by abolitionists to bring about change.

The question is never whether one has the right to protest. The question is how to protest well.

In recent years, I have watched demonstrations take forms that seem more interested in confrontation than persuasion: blocking officials and and other civilians from entering buildings, occupying offices, shouting down speakers, harassing bystanders on their way to work, even destroying property. These actions may satisfy the passions of the moment, but they rarely strengthen the cause. More often they alienate potential allies, harden the opposition, and give critics an excuse to dismiss the substance of the protest altogether. The tragedy is that the cause itself may be just, but the manner of advocacy makes it harder, not easier, for others to listen.

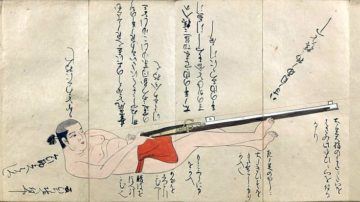

A historical parallel makes the case well. Read more »

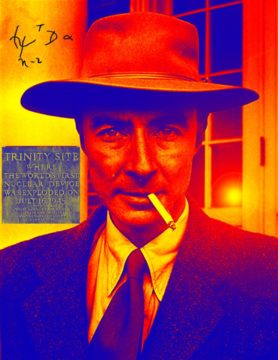

In October last year, Charles Oppenheimer and I wrote a

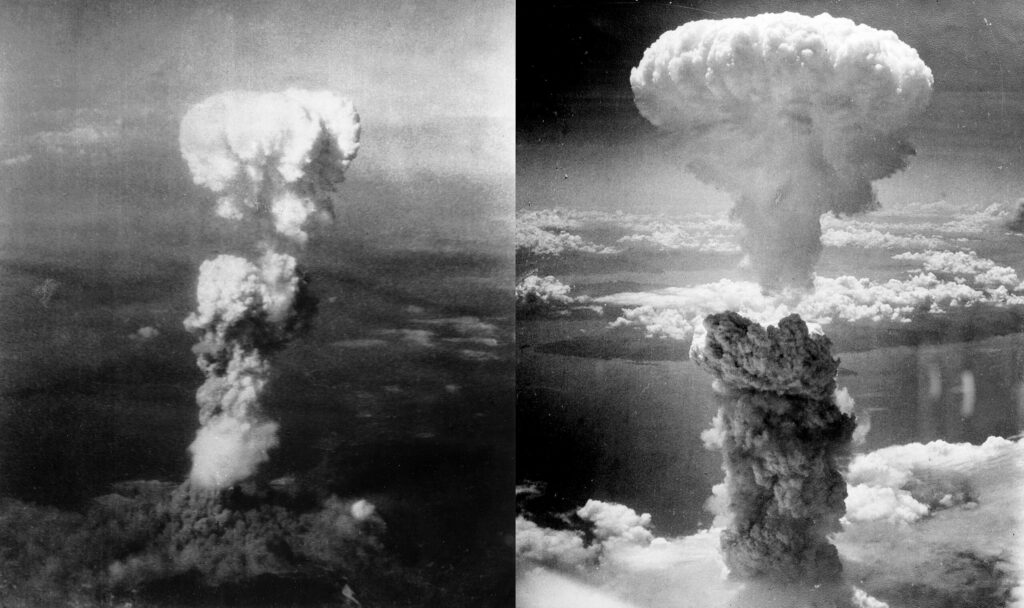

In October last year, Charles Oppenheimer and I wrote a  As the saying goes, if you believe only fascists guard borders, then you will ensure that only fascists will guard borders. The same principle applies to scientists working on nuclear weapons. If you believe that only Strangelovian warmongers work on nuclear weapons, you run the risk of ensuring that only such characters will do it.

As the saying goes, if you believe only fascists guard borders, then you will ensure that only fascists will guard borders. The same principle applies to scientists working on nuclear weapons. If you believe that only Strangelovian warmongers work on nuclear weapons, you run the risk of ensuring that only such characters will do it.