by Barbara Fischkin

Eight weeks have passed since I wrote about my Cousin Bernie—and how, posthumously, he adds to my own memories of him. As readers may remember from my last offering, Cousin Bernie’s widow, Joan Hamilton Morris, sent me the pages of an incomplete memoir her late husband pecked out on a vintage typewriter in an adult education class he took after retiring as a university professor of psychology and mathematics.

If Cousin Bernie were alive today he would be 102. Those pages of memoir chapters, some more worn than others, remain in a place of honor, tucked into a corner of my own writing table. I feel that “Cousin Joanie,” as I call his widow, sent them to me for safekeeping—and for presentation to the world. Originally I thought I could do this in one or two chapters. A deeper read has revealed a surprising amount of insight. Here is my fourth take on my cousin, who fascinates me despite his evergreen persona as a nerdy, chubby, lost boy from Brooklyn. There will be a fifth offering and probably a sixth. If it seems Bernie is taking over my memoir, I am fine with this. I have written a lot about my mother’s side of the family. Now it is my father’s family’s turn. And what better way to bring them into the light, than through Cousin Bernie?

What follows is Cousin Bernie, Part Four. I’ve only edited it slightly, less so I think than his Adult Education teacher. So far, my minor editing has provoked no lightning bolts from the heavens. I have discovered another Bernie, a child who believed he could fly like his comic strip hero.

“I was eight years old, and my sister, Gertie, six. We had just been transplanted to Bridgeport, Connecticut from Brooklyn, New York. My father, a home painter and decorator, felt that he could do better in terms of finding work in a smaller city.

“Here, a whole new set of stimuli presented itself: A Benjamin Franklin stove in the kitchen, a gas water heater in the bathroom, which had to be lighted so we could bathe, and a coal bin on the back porch. There was a scuttle for bringing in coal for the stove. The Saturday Sabbath meal preparations—gefilte fish, stewed chicken and beef, challahs, cookies and pies—began as early as Wednesday night. The stove was banked and allowed to go out on Saturday night.

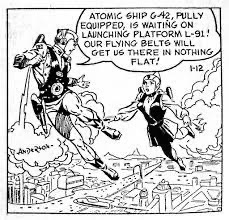

“We slept as the stove died down and, on Sunday mornings, my sister and I would climb into my parents’ big bed. Pop got up wearing his union suit, put on a robe, removed the ashes, kindled a new fire in the stove and came back to bed with us for my reading of the Sunday comics. My sister, Gertie, pointed to each speech bubble, as I read them. It seemed to me that Andy Gump’s nose or chin was strange looking. I disliked it when the bubbles were long. But it was here in the Sunday comics that I encountered the adventures of ‘Buck Rodgers in the Twenty-Fifth Century.’

Cousin Bernie as Buck Rogers

“‘C’mon,’” I said to my trusted corporal. (a.k.a. my baby sister, Gertie). ‘Put on that army belt and we’ll play.’

“Next to where we lived there was a one story, automobile garage where Mr. Samuels, a friend of my father’s, was the master mechanic. He had just wheeled the dolly out from under a car, sat up, reached for a cigar stub from his ash tray on the floor when he saw the troops (still only Gertie and myself) converging on him. Over the years, the two of us had accumulated three or four wide army belts, some with ammunition pockets. It was these that we were wearing that day. I don’t know if they were the same ones as Buck Rogers wore. But I liked to think so.

“‘Well, children,’ Mr. Samuels, the master mechanic, said. ‘What can I do for you today? Maybe sell you a new car?’

“‘I want to buy some cans of floating power to put in these belt pockets so maybe we can fly like Buck Rogers,’ said I.

“Floating power? Where did you hear of it?” he asked in an amused and somewhat puzzled manner. “Am I supposed to stock it?”

“In the ads they say that new cars have floating power.”

Mr. Samuels took a puff on his cigar. “Bernie, Gertie,” he said. “Those are just advertising words. You are supposed to feel that you are floating along in those cars. But really nobody can fly today, except on an airplane. Sorry, children, I have to get back to work.” Saying that, he placed his cigar stub back on the rim of the ashtray.

I don’t know about Gertie, but I was really shot-down. Since then I have been suspicious about advertising claims.”

Cousin Bernie Reflects On His First Attempt to Fly

(Or: Why Floating Power Was a Better Idea)

“In 1929 I was six years old and my sister Gertie was four. We lived on the top floor of a two-family brick house in a residential upper-middle class section of Brooklyn. On the back and sides of our house there were extensive concrete sidewalks. Here and there a square was left open for a growing tree. The concrete provided a flat surface for us to play on and for me to ride my tricycle.

Twenty feet or so from the back of our house, there was a one-story flat-roofed garage that belonged to the house on the next street over. The roof sloped slightly away from our yard and was surrounded by a low barrier on three sides, opening up to our backyard and yet another play area.

This back yard was an ideal place. Our mother could watch us from her second story kitchen window. Gertie usually set up a small table and chairs. Here, she and her girlfriend and their dolls could play house and drink tea from her tin tea set. My own friend and I rode our trikes from the sidewalks to the yard, often in time to untie the lunch or refreshments my mother would lower in a basket on a clothesline rope.

Television was years away. And while we had heard and seen radios, our family would not own one until the mid-thirties. We did see newspapers with illustrations, and heard much adult gossip. The talk of the day was about the “Lone Eagle,” Lucky Lindy and his 1927 crossing of the Atlantic. There was airmail. There were parachute drops from towers at amusement parks. There were stories and pictures of dare-devil aviators walking the wings of the flimsy barn-storming airplanes over open country. And, of course, as of the beginning of 1929, there was also Buck Rogers.

On one sunny, summer afternoon, I hatched a brilliant idea. All was in readiness. The girls were having their tea party. My young friend and I found this wooden ladder and climbed to the top of the flat garage roof. With my friend’s help, we managed to hoist up my trike. With line rope, we fastened a big black umbrella under its seat bar and to the handle bar.

The pilot was ready.

If parachutes could support a person in the air, then I should certainly descend through the air slowly and safely. The air was more important. What was needed was fast, rushing air and then uplift. Uplift! So, with my chum cheering me on, I drove my trike faster and faster and faster around the roof. I must have felt some fullness in the umbrella when I flew off the back of the garage roof.

Gertie and her friend and their dolls were still drinking tea. My chum had screamed at take-off time and my mother had her head outside the upstairs window.

My bike and I lay sideways on the concrete.

I extricated my hurt, bruised self from under the seat of the trike. Half of the large front wheel was bent at a right angle to the other half. The umbrella was upright. But it had turned inside out.

Phooey, I had failed to fly.

What was needed, of course, was a stronger umbrella and more uplift.”

——-

I do not know if Cousin Bernie tried to fly again, at least not without an airplane ticket in hand.

I do know that he must have had strength and wits comparable to Buck Rogers to survive the next part of his life, his mother’s descent into madness and her institutionalization for the rest of her life.

I will be presenting his writing on this, in my next offering, in November.