by Herbert Harris

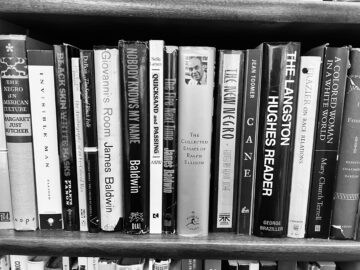

The greatest privilege of my childhood was growing up in a house where books had their own room.

My father’s library occupied the second floor, the only room without a window air-conditioning unit. On summer afternoons in Washington, DC, when the heat and humidity pressed down like a weight, the rest of the house hummed and rattled with machines straining to keep up. The air in the library stayed stubbornly still. It was the early 1970s, and I was on summer break after tenth grade, retreating there to find the peculiar solitude this room alone offered. Each book I opened sent up a cloud of dust that glittered in the angled sunlight. Shutting the door turned the room into a sauna, but in that quiet stillness, I didn’t mind. It felt like the price of admission to a different world.

The previous summer had unfolded differently. I had just finished ninth grade, where we surveyed the classics of English literature and retraced the decisive moments of Western civilization, reliving the deeds of its great men and women. I spent long afternoons in the library, sinking into those books as the heat pooled around me. I melted into a reclining chair and wandered through the past. That immersion had felt complete, even sufficient. But this summer, I arrived with a different appetite. I was growing skeptical of the Eurocentric narratives threaded through everything I was learning. I sensed there were other stories and vantage points, and I came looking for them.

I picked up the book I had been reading a few days earlier and turned to the page marked with an index card. I searched for the sentence I remembered, but at first the words slipped past me. James Baldwin was writing about a Swiss village, about children shouting “Neger” as he walked through the snow. Seeing the word on the page registered instantly, not as surprise but as recognition. I had learned early what it meant to be called that name in its American form. That knowledge had settled into my body long before I could articulate it. Read more »

It’s Monday, 1:45, and six men and I sit in a circle with our German-trained psychotherapist, an imperious woman who reminds us that she is here to help only if we get bogged down or offer guidance and that we men need to find our own way through our turmoil, which is the point of the group and the point of each of us paying $3000 per year. I’m fairly new, so before I speak, I’m seeking some level of comfort or commonality among us, and every week I come up short. I’m not yet adjusted and unsure what I should be adjusting to.

It’s Monday, 1:45, and six men and I sit in a circle with our German-trained psychotherapist, an imperious woman who reminds us that she is here to help only if we get bogged down or offer guidance and that we men need to find our own way through our turmoil, which is the point of the group and the point of each of us paying $3000 per year. I’m fairly new, so before I speak, I’m seeking some level of comfort or commonality among us, and every week I come up short. I’m not yet adjusted and unsure what I should be adjusting to.