by David Kordahl

Government secrecy makes UFO claims impossible to verify—or disprove.

When I lived in Arizona, my next-door neighbor once told me that he had seen a time machine. These types of anecdotes are not uncommon in Arizona, out on the edge of the world. At the time, I was in graduate school for physics at Arizona State, and I presumed my neighbor was either lying or confused. He had seen the time machine, he told me, behind the door of a restricted area of his former employer, a defense contractor in Tucson. I nodded politely and let it slide, much as I would for the claims from our neighborhood Mormon missionaries or the 9/11 Truthers whose stand I passed daily on my walk to the cafeteria.

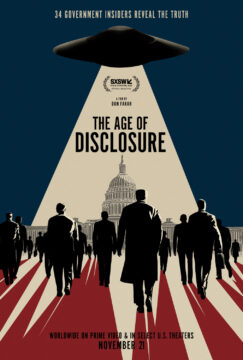

I was thinking about my old neighbor when I recently came across a clip of Joe Rogan speaking with Dan Farah, the director of a new documentary, The Age of Disclosure. If Farah is to be believed, my neighbor might indeed have seen something behind that door. The Age of Disclosure claims that crashed Unidentified Aerial Phenomena—and, yes, UAPs are just UFOs by another name—have been studied by defense contractors for some eight decades, and that failing to take them seriously poses a risk to national security.

Regular readers will know that UFOs and US government secrecy are both part of my beat here at 3QD, so I grabbed my tinfoil hat and pressed play.

The Age of Disclosure tells a story that, as many critics have noted, is by now pretty familiar, which doesn’t stop it from being pretty crazy. The vibe of the film owes much to conspiracy thrillers like The Parallax View or JFK, with frequent solemn shots of national monuments thrumming to a continuous soundtrack. A good deal of the runtime is filled by montages of dark-suited men saying things like “UAPs are real, they’re here, and they’re not human.” The movie’s poster tagline, “34 Government Insiders Reveal the Truth,” gives a good idea about what it offers: clips of military, intelligence, and congressional officials affirming, on the record and under their own names, that they think UFOs are a real concern. Read more »