by Rafaël Newman

At the University of Toronto one winter term in the mid-1980s I took an undergraduate course on classical philology. The instructor was Hugh Mason, a British-born Marxist who once reproved me for wearing a white dress shirt to give a presentation, something he maintained “only a fascist” would have done in his day. (My own politico-sartorial instructions, meanwhile, were issued by The Clash, who cautioned strongly against a wardrobe featuring the colors blue and brown unless one were already “working for the clampdown”). The course was spent for the most part learning about celebrated pioneers of the study of Greek and Latin—among them Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff, better known beyond the world of classical antiquity for his dispute with Nietzsche—; but there was also a unit on something called Proto-Indo-European.

PIE, as it is commonly abbreviated, is the hypothetical “mother” of the large, widespread family of tongues comprising Greek, Latin, English, French, and German, but also Russian, Farsi, Lithuanian, Albanian, and Hindi, among many others. Their linguistic ancestor can only be theorized, following the discoveries of British colonial philologists in 18th-century India who compared Sanskrit with Ancient Greek: because there are no written records of languages spoken longer ago than a few millennia.

A putative PIE vocabulary, we learned from Professor Mason, must thus be reconstructed by surveying the modern languages identified as cognate descendants of the earlier idiom for similarly sounding words with related meanings—such as, famously, μήτηρ/mater/mère/Mutter/mother—and using established laws of phonetic evolution to reverse-engineer as their forebear *méh₂tēr (the subscript stands for a particular quality of aspirate, while the asterisk indicates that the word is hypothetical). The PIE reconstruction I recall best from the course, however, and which had no doubt been chosen (or perhaps invented) to reflect the climatic conditions in which we were gathering, in Toronto in February, was *sneghweti: “It is snowing”.

The study of Proto-Indo-European has developed considerably over the past 40 years, since I was first introduced to the idea that winter day in Toronto, its evolution driven by significant technological advances, particularly in the fields of archeology and genetics. In Proto: How One Ancient Language Went Global, Laura Spinney gives an absorbing account of the latest attempts to identify and trace the speakers of Proto-Indo-European. Spinney, a science journalist, surveys archaeologists, geneticists, and linguists who are reconstructing not only the way those prehistoric peoples spoke, but also how they lived.

Among the cultural artifacts—or “institutions”—experts have determined to have been typical of the hunter-gatherers, farmers, and nomads who converged in the steppes and around the Black Sea several millennia ago, and migrated from there, with their languages, into present-day Europe and Asia, are aspects of their diet, religious beliefs and burial customs, as well as, intriguingly, the central role they accorded uncles in socializing their children.

I had occasion to participate in some of these ancient but enduring cultural institutions myself when we bade my father farewell last month, on the first anniversary of his death: for our gathering, which of course centrally comprised culinary and funereal elements, was as much about his brother, my uncle, as it was about my father himself. Or rather, it also featured my father in his capacity as an uncle, and thus lent extra credence to the theory, sketched by Spinney, of an important avuncular presence in the lives of young Proto-Indo-Europeans.1

Coleman Joseph Newman, whose Hebrew name was Kalman Yussef but whom people called Jerry or CJ, died in Montreal, the city of his birth, on August 3, 2024: and thus his Yahrzeit, the occasion for a traditional Jewish commemoration, fell this past month, in August 2025. (We had initially considered holding a “celebration of life” on February 17 of this year, which would have been his 90th birthday—until we remembered how dire the weather conditions in Montreal would be during that period.) Although my brother’s telephone report of our father’s death, at the age of 89, had produced in me an unexpectedly sharp pang of sorrow and loss, I had of course been steeling myself for the news over the last couple of years, and had already begun to say goodbye in my mind. Dad’s younger brother, however, had predeceased him by more than forty years, when he was just 37; and when word of his death came, it was a cataclysmic shock to us all.

Nathan Theodore Newman was born in Montreal on July 13, 1943. He was given as his Hebrew name Nafthuli Tuwje, after his father’s father—my scoundrel great-grandfather—who began his life in Czarist Russia in the 19th century and ended it in the mid-20th somewhere in Michigan, where he had started anew after abandoning his second family in Quebec and serving time for embezzlement. My Uncle Ted or Teddy, as he would eventually be known, grew up in the aftermath of the Second World War, as news of the mass murder of European Jews was broadcast with ever greater credibility and his parents (my grandparents) contended with the management of a clothing business—with bankruptcy, and with the founding of a new factory on the ruins of the old—and with various shades of angst. My grandmother called Teddy “my depression baby”. If she had in fact suffered from a postpartum depression, however, she had recovered by the time I came along, since I remember my Bubbi as a cheerful and affectionate grandmother. Or perhaps she was simply adept at hiding her malaise.

For his part, Uncle Teddy seems to have inherited this sadness, which he treated—or camouflaged—after his own fashion. He was famously beautiful and creative as well as given to fits of despair, whether existential or aesthetic: when for example during his late adolescence his parents were considering a move from the atmospheric tenements and outside staircases of Montreal’s Plateau neighborhood, not yet rendered desirable by gentrification, to the relative elegance of Snowdon, where they could join fellow European immigrants on their way out of the working class, he pleaded with them for his sake to take a vintage apartment with character, rather than the soulless all mod cons of a bourgeois new build.

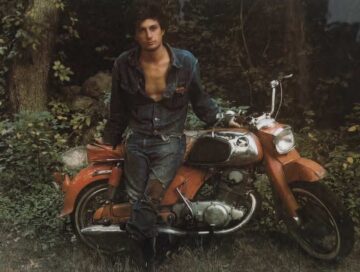

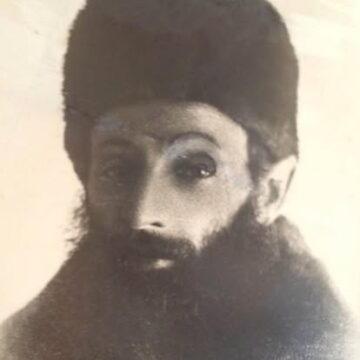

But my Bubbi and Zaideh did in fact settle in such sterile environs, and Teddy took off, riding his motorcycle south to Martha’s Vineyard, where he joined a community of artists and was portrayed James Dean-style by the celebrated photographer Marie Cosindas. He learned drawing, pottery, and enough architecture to eventually construct a Buckminster Fuller-inspired geodesic dome; his persistent melancholy, however, was never completely alleviated, neither by periodic stays at the notorious Allan Memorial Institute in Montreal, nor by dedicated self-medication with cannabis. (When, between relationships, Teddy was living with us for a time in British Columbia, my mother once used patchouli oil in an attempt to mask the scent before her mother came to visit: which hippie-connotated fragrance my Grossmutti in any case mistook for “Marie-hwanna”.)

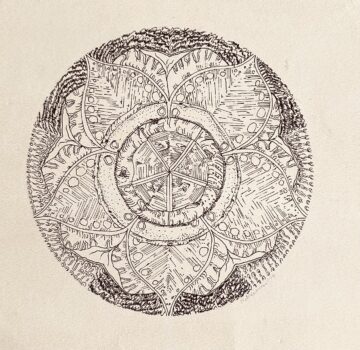

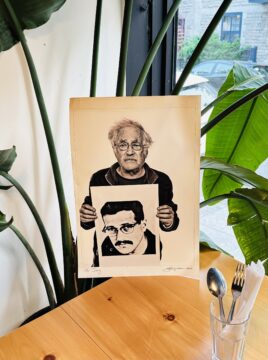

Despite his unhappiness, however, in the 1960s and 70s Teddy’s mixture of DIY, art-school chops, neo-romantic sex appeal, and drug-induced rejection of the establishment rendered him a perfect creature of the zeitgeist. He produced marvelously intricate pen-and-ink mandalas and caricatures reminiscent of John Lennon, and distorted language with exhilarating freedom and idiosyncratic whimsy (which is in part why I used a photograph of him in a recent post on linguistic development). I benefited, in early adolescence, from my uncle’s maverick dietary counsel—avoid salt, don’t drink anything to accompany your meals, lest it wash away beneficent gastric acids—derived from the faddish company he kept, and inherited all of the navy-blue items in his wardrobe when he decided to dress exclusively in tones of red and orange to enjoy their more salutary chromatic vibrations. (Come to think of it, Teddy may have thus preceded Joe Strummer as my ideological fashion arbiter.) My uncle was also always good for a zany, ribald bon mot. To this day my brother half winces, half beams at the sobriquet Teddy bestowed on him when, perhaps five or six years old, Adam interrupted a conversation among adults to demand a new plastic action figure (likely a Big Jim rather than a GI Joe) and Teddy dubbed the impetuous, appetitive little boy Buy Me Sex Muscle.

But my uncle’s half-feigned chagrin at the trials of child-rearing didn’t stop him from reproducing himself, in the form of three daughters, born over a decade with two different partners: my cousins, who grew up variously in rural Ontario, in upstate New York, and on Gabriola, an island off the coast of British Columbia.

Teddy died in January 1981, accidentally, during the course of a radical fasting cure at an ashram on Lake Tahoe. The girls were around 12, 5, and 2 years old at the time, and Teddy’s estrangement from the mother of one of them, and the relative youth of the other two, meant that none of his children attended the funeral in Montreal.

Which was just as well, since the event was, even for me at the advanced age of 16, made up of shattering details: the rabbi’s fulsome, euphemism-laced eulogy; my Zaideh’s alienatingly matter-of-fact tone as he spoke to well-wishing business partners; my Bubbi’s kind face swollen with tears; and, most awful of all, the sight of my father, apparently blown backward by grief into his chair as I entered the viewing room at Paperman’s Funeral Parlour, where the undertakers had just closed the casket. So I was relieved when I was not expected to make the drive out to the Baron de Hirsch Cemetery following the ceremony, where the casket was lowered into the ground that day, before we returned to my grandparents’ place, not far away on Bourret Avenue, to sit shivah.

*

I finally made it to Baron de Hirsch this past month, more than 44 years later. We had gathered the night before—Jerry’s children, his nieces, and a selection of our own children and nieces—at a southeast Asian restaurant in the Plateau dad would have liked. We placed a portrait of him in the corner and spent the evening reuniting with our distant relatives (or meeting them for the first time, in some cases), passing around old photographs, and telling jokes. The next day, in a party of a dozen, we headed to the cemetery.

The Baron de Hirsch-Back River Cemeteries, the facility’s new name since the fusion of two graveyards in 2012, are an enormous field, with sections marked out for Montreal’s various Jewish congregations. Our goal, this past August 3, was the plot reserved for Beth ha’Medresh ha’Gadol, the synagogue attended by our Bubbi and Zaideh, who now lie buried in Baron de Hirsch as well. High above the whole area waves a large Canadian flag, next to a pole flying the flag of Israel, a sign of the staunch Zionism of Montreal’s conservative communities; and as we passed the mogen dovid, two of our number quickly pinned watermelon emblems to their jerseys, in a performative apotropaic gesture.

When we had located the gravesite, thanks to directions retrieved by Galen, Teddy’s eldest daughter, we placed pebbles on Bubbi and Zaideh’s joint headstone and on Teddy’s single marker, examined our grandparents’ footstones, engraved with their names and dates, surreptitiously strowed some of dad’s ashes among the stones, and spent an hour there together, our silence alternating with reminiscence. And when I came to speak quietly with Tashi, Teddy’s second daughter, a former skater punk turned ADHD counselor, I understood why she had been so eager to hold the event: indeed, why her messages to me following dad’s death last year, inquiring eagerly after our plans for a “celebration of life,” had strengthened me in my resolve to organize such an occasion.

Before Teddy left Gabriola for the ashram in 1981, Tashi told me at the cemetery, she had pleaded with her father to be taken along—only to be told that she was too young, that the process he was going to undergo there was too rigorous for a child. And when he then unexpectedly died while on his sojourn, and Tashi was unable even to attend the funeral in Montreal, she was left with a haunting regret, amplified by childish incomprehension. Her consolation, during the years that ensued and until he left the west coast around the turn of the millennium to return to the city of his birth, was my father—her uncle—who provided her with a connection to the father she had lost, and to the family back east she had never properly come to know.

And so here was an echo of that ancient, putative, reconstructed Proto-Indo-European institution Spinney has written about, the role of the uncle in childrearing: the uncle as substitute or supplementary father, both potentially closer and usefully more distant than one’s actual progenitor, a source of wisdom and comfort unencumbered by the petty quotidian concerns of material existence.2

As for dad, he had loved his brother, probably as much as he could love anyone. He dedicated Sudden Proclamations, his 1992 collection of poetry, “To the memory of my brother, Ted”. There are in fact two poems for Teddy in the book, one in which dad calls him “my dead brother, / my late lover, dead at 37, / never to return,” and another in which he recalls with poignant desperation Teddy’s disappointment at the hardness of life, and his retreat into drugs and resignation: “I feel like kicking him. Maybe / that’s all that love has left for me to do.”

It must have been a consolation for dad as well, then, to maintain a connection to Teddy in the form of his dead brother’s children, Galen, Tashi, and Gabe, and to continue to experience with Teddy’s avatars the solicitous, protective, paternal feelings he had had for their father—a vicarious affection that was clearly appreciated by its recipients. And as Tashi was telling me about her gratitude to my father for this living link to her dad, she mentioned her own kids, and, in passing, the fact that she had given her eldest daughter, soon after her birth, the title “Captain”—because she realized that this tiny being was going to be ordering her about.

At which I suddenly recalled that my father had been accustomed to referring to her father, to Teddy, with fond exasperation as “Captain Head”—both a commanding presence in my father’s life, and a vulnerable head case. When I told Tashi about that name, and determined that she had never heard about this eccentric bit of family custom, it was as if we had excavated an ancient lineage, evidence of a cultural reflex passed on through the generations.

And when Tashi propped up against Teddy’s gravestone the skateboard she had carried with her from her home in BC, a skateboard her partner had had adorned for her with the Marie Cosindas image of her father, I was reminded of the antique funerary rituals of the various Proto-Indo-European tribes, their habit of burying artifacts with their honored dead to accompany them into the beyond. And I was glad that I could finally be at the cemetery that day, in my own capacity as father and uncle, celebrating a prehistoric rite made new by our peculiarly modern presence.3

_________________________________________

1 I realize that Semitic languages and cultures do not belong to the Indo-European family. Nevertheless, since my father’s family’s more immediate roots are in central and eastern Europe, among Slavic and Germanic speakers, I feel justified in identifying an Indo-European strain in his heritage.

2 In fact, the evidence for avuncular rearing among Proto-Indo-European peoples suggests that the role was regularly accorded a maternal uncle—that is, one on the mother’s side. Now, during my trip to Canada in August I also had occasion to spend time with just such an uncle, my mother’s sister’s husband. Freddy, who recently turned 90, is not letting incipient blindness prevent him from drafting a memoir of his career as a diplomat during the Cold War. He is a most admirable, formidably learned, and utterly decent person, a child survivor of the Shoah whom I witnessed facing down the absurd and shameful charge, made by one of the watermelon-wearers, that he had no right to discuss the term “genocide” in its application to Gaza. I am enormously grateful to Freddy for many things, chief among them his invention of “scary stories without monsters” with which to regale us children at bedtime: he demonstrated to me the potential pleasures of narrative, and of extempore speaking, and thus helped prepare me for my present calling.

3 As it happens, Laura Spinney’s book was a gift from my brother, who was of course also present at our commemoration on August 3 and is himself a father of two, and now also a grandfather (or Zaideh) three times over—as well as a cherished uncle to my own two daughters.