by Leanne Ogasawara

1.

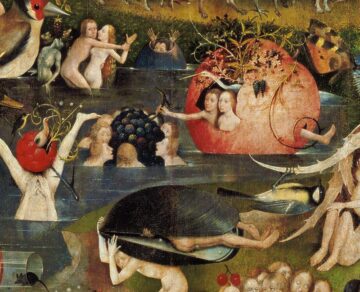

Standing before Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights in the Prado is an act of surrender. Eyes are consumed by details: naked bodies cavorting in crystalline ponds, human-sized strawberries and a multitude of dripping cherries. There are birds devouring humans, whilst cities are collapsing into flames at the far edge of vision. Each figure is rendered with miniature precision, yet together they overwhelm, producing an excess that resists containment.

Bosch offers no single story; the painting’s power lies in its refusal to be reduced. It is “too much”—and therein lies its meaning. I was not surprised, therefore, to find details from the painting on the cover of Becca Rothfeld’s 2024 book All Things Are Too Small: Essays in Praise of Excess. I had heard so much about this book before finally picking up a copy. Offering a strong critique of our contemporary aesthetics of minimalism, I thought it was a perfect book to pack for my summer of writing. First, working on a novel manuscript at two writers’ residencies, one in Vermont and the next in Virginia, I then made my way to the Sewanee Writers’ Conference and then to Bread Loaf. It was two-and-a-half months living out of a small suitcase with that one book along for the ride– in hardcover, of course.

From Marie Kondo’s call for us to “take out the trash” –where trash is defined as anything we are not currently using and enjoying– to the multi-million-dollar mindfulness industry, which similarly sells ways for us to de-clutter, Rothfeld’s book asks us to consider that less is not always more.

Sure, sometimes it is.

Especially for Americans whose lives do so often seem to be spinning out of control, not least of all because of all the stuff we endlessly buy and throw away, by all the choices we have, and how these endless choices seem to define who we are. Maybe for people constantly loading up at Costco and traveling overseas several times a year, with households with so many moving parts, a car per person, Kondo’s style of clean consumerism can feel like a relief, of sorts. I get it.

Rothfeld writes:

I DREAM OF a house stuffed floor to ceiling; rooms so overfull they prevent entry; too many books for the shelves; fictions brimming with facts but, more importantly, flush with form; long tomes in too many volumes; sentences that swerve on for pages; clauses like jewels strung onto necklaces; a kitchen crammed with cream, melting butter, sweating cheese. Clothes on the floor, shoes on the bed, blood rusted on the sheets, mud loaming all the carpets, and a table set for a banquet bigger than I could ever host. I want all this precisely because I do not need it.

Yes, yes, and yes.

Best known as a book critic for places like the Washington Post and Book Forum, Rothfeld spends a lot of time talking about the trend in minimalism in literature—which is my main interest. She argues that contemporary literature has become over-invested in the miniature: fragments, lyric interiors, scenes carefully carved down to the precise image. This fetishization of the small, she insists, has left us with writing that is elegant but diminished, modest to the point of timidity –she is thinking of writers like Maggie Nelson and Sally Rooney. Rothfeld does not scorn detail; she scorns the notion that detail alone suffices. What she calls for instead is capaciousness, an ambition that risks disorder in an attempt to grasp more of the world.

All Things Are Too Small is a book about pleasures that defy disciplines of control.

I have been thinking a lot about how controlled and constrained I have felt in the U.S since my return in 2011 from Japan. Many people might imagine life in Japan to be constrained. And in so many ways it is. It has not been called the “straight-jacket society” for nothing. And yet, it was in coming home to California when I personally felt more policed and controlled than ever before in my life. Financially, in parenting, in posting online—even in home decorations and yes, very much in my writing.

For example, whenever I workshop my fiction, I make a “workshop version,” in which all complex verbs are changed to simple present or simple past (no passive tense, etc.) and all semi-colons are removed… or “cleansed,” as I like to call it. I do consider things like my characters’ genders and ethnic backgrounds—but that is minor compared to the fear of having my workshop group over-focusing on things like backstory or –horror!—what they call “infodumps.”

Like in home décor among the aspiring wealthy, in literary fiction in the US minimalism reigns supreme. You can really hear the journalistic style of clear, short sentences with simple grammatical constructions when a work is read aloud. It is not a bad thing either. Coming from a love of Japanese literature, I do admire simple elegance. I am currently reading David Szalay’s Booker longlisted novel Flesh. Written in extremely compressed prose, it is a triumph of minimalism. I love it, as I loved Katie Kitamura’s Audition–also on the list and also written in spare prose. These books are among my favorites of 2025.

But I also sometimes crave what Becca Rothfeld calls a more maximalist style.

And anyway, who decided that writers of fiction can’t use adverbs? Or can’t include exposition or have compound sentence structures? Who said writing needs to be pared down to its cleanest bone. Who says that a good story must be one that compresses life into the arc of cause and effect, stripped of ornament, resolved with journalistic clarity.

In my experience in workshops, to attempt excess in my stories was to risk critique; to sprawl was to fail. Minimalism was not just a style but an ethic, a posture of seriousness. Exposition and back story had to be “earned,” whatever that means.

The famous literary critic James Wood articulated this perhaps better than anyone in his famous critique of what he calls the “hysterical realist” novels.

The famous literary critic James Wood articulated this perhaps better than anyone in his famous critique of what he calls the “hysterical realist” novels.

It is an unfortunate term since it doesn’t convey what he means. Basically Wood is trying to unpack issues he has with “big novels,” for example those by Zadie Smith or Salman Rushdie or David Foster Wallace, in which stories revolve around a large cast of point-of-view characters and involve many digressions and coincidences—”like a rock musician who, when born, begins immediately to play air guitar in his crib (Rushdie)”… or “like in one of Smith’s novels, twins, one in Bangladesh and one in London, who both break their noses at about the same time.”

Novels like those by the above authors are overly long, he says, and have “frantic plots, which are filled with excessive secondary information that obscures the central story.” Wood is advocating for a rigorous approach to feeling and aesthetic judgments, believing that the purpose of the novel is to be deeply affecting, not to overwhelm the reader with unnecessary details.

After Wood’s famous essay on hysterical realism came out in the Prospect in 2000, Zadie Smith responded in a circumspect manner saying basically that, yes, she also loves the realism of Madame Bovary—but shouldn’t there be room for Rushdie and Pynchon too?

Taste is fundamentally a personal matter, right?

And yet, in my own workshops, I have seen how narrow people’s tastes can be. The majority of readers I have met read to be transported. They seek to have a mind-meld with the characters—or in Wood’s terms, to feel something of another person’s soul by walking around inside their heads. Great fiction can really do this. It’s true, I think, that the “hysterical” lose this intimacy with characters and the arcs of their lives, and yes, they often contain a lot of what Wood’s derisively calls “information”—but as one reader and therefore one point on the graph I personally love big fiction. And so does Rothfeld, whose favorite author, by the way, is the great Norman Rush (whose books also have covers displaying details from Bosch’s Garden).

2.

2.

There is a famous story about how King Philip II of Spain died while gazing at his favorite painting, The Garden of Earthly Delights.

All he could think of, as he lay there in his death bed, was the heaps of luscious fruits, those pomegranates, berries, and cherries. The painting was dripping in strawberries, which was why in his mind he always referred to it as his strawberry painting.

The trip from Madrid had been excruciating.

Carried through the heat in the royal palanquin, every step had been a torture. His gout made rest impossible. Not to mention the smell from the putrefying sores that covered his legs—was it any wonder his mind took such a morbid turn? He was dying, for God’s sake. And in the end, all he could think of was those strawberries.

Arriving at el Escorial at last, the servants moved him into his chambers. The bed took up every available piece of space. He saw with pleasure that the servants had arranged for the small opening in the wall, the one he’d commanded them to prepare, through which he had a direct view down on the High Altar in the basilica he’d constructed below. So now, he could watch Mass being celebrated without even needing to get up.

After they tucked him in his bed, he commanded the servants to bring him “the painting.”

But to his shock, the painting was not immediately delivered. Instead, trouble arrived at the foot of the bed in the guise of one of his padres.

“Of all the pictures in the world, this is a strange choice. Are you sure, majesty?”

“Of all the pictures in the world, this is a strange choice. Are you sure, majesty?”

Before the great King had the chance to reply –and his response would have been ferocious—the priest continued, demanding: “Where in the Bible can you find people frolicking naked with peacocks and fish in orgiastic abandon?”

Philip was, after all, the great defender of Catholic Europe against the scourge of the Ottoman Empire and even worse, much worse, that of the Protestant Reformation.

He knew his role. But he was adamant. He would look upon his favorite painting in the world at the moment of death. And so, the servants hung the Garden in front of his bed. After looking at his vast collection of relics–smelling and kissing each one last time– he spent the last hours of life gazing on it.

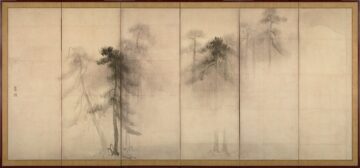

Before seeing the Garden for myself, not all that long ago, I would have said the painting that I would like to see at the moment of my death was Hasegawa Tōhaku’s Pine Trees.

Painted in the calligraphic style of Chinese ink wash painting in the late 16th century, the screens (now in the Tokyo National Museum) were designated as a National Treasure of Japan in the 1950s. Depicting Japanese pine trees coming in and out of focus in mist, the trees appear to be in motion. Brushstrokes fast and abbreviated, the white space in the painting does a lot of the work.

Around the time Tōhaku was painting his pines, Japanese aristocrats also were gazing at certain pictures as they lie on their deathbeds. Like Philip II of Spain. Imagining heaven as a beautiful blue-green landscape, covered in hills and mist-covered valleys, polychrome ink paintings often situated a lonely hut amidst the lush scenery. In such a setting, it was believed that Amida would descend on purple clouds from paradise to meet the faithful. As long as the believer chanted Amida’s name faithfully, the Buddha of Light would come to escort them back to the land of bliss. Called raigo-zu, these paintings of “Amida’s Welcoming Descent.”

How wonderful to have pictures of salvation to look at as we are dying—even at the moment of death?

Like portals to heaven.

Like portals to heaven.

The minimalist pine trees are like that.

And what of Bosch’s super maximalist triptych?

As a friend says, “As much as I appreciate Bosch’s paintings, I don’t think I’d want it to be the last piece of art I see. Still, it would be instructive…”

But this was the picture Philip wanted.

His favorite painting in the world, it would be the final thing he looked at before seeing his last. Not the faces of his wife or children. Not even the faces of his grandchildren. Nor even his beloved dog. Philip wanted to enter the world of the Garden of Earthly Delights once and for all. To count all the birds in it: the spiraling flocks of starlings and posing peacocks and pheasants, the storks and kingfishers, egrets and jackdaws. And to sit underneath one of those strawberry trees.

This was, he was sure, a place he could spend an eternity.

Reading Rothfeld’s book this summer, I was thinking how our lives online have made us more and more attuned to what we “like,” and the way our consumer choices have somehow come to define us… from what we eat and where we buy our food to our decorating choices, even our literary favorites –which are ultimately issues of style not really morality. These things have become more and more how we define ourselves. Like how overweight characters in a novel have become a lazy stand-in for negative traits in characters so too have heavy sentences and thick books filled with exposition or back story—sentences clunky with adverbs—have come to be considered “too much.”

We want our houses and minds, even our prose to be streamlined, like the writing we read online. As a person who has lived in a spare Japanese home before living in a more ornate Spanish colonial with velvet curtains and antique fixtures to then happily downsizing—even buying all the furniture in the new place so that I literally stepped into someone else’s life…. I would only say that life is short– and like Rothfeld, I want it all! Want to try and savor many things, read all kinds of books, listen to many styles of music. And more than anything –at least when I read fiction– I want to be surprised and to see new worlds open.

Of course this is obvious, and yet Rothfeld’s book felt really thrilling to read.

So, yes, here’s to a little excess!

- For more about Bosch’s Garden, please see my essay in Aeon, Birdwatching in Oil Painting.

- For more about the portals to heaven on my Substack (essay was originally published in Entropy but they disappeared from the Internet, so I a reproducing part of it on my Dreaming in Japanese Substack.

- For my experience at Bread Loaf and Robert Frost in 2023, please see my 3QD essay, “Robert Frost’s Ghost: The Bread Loaf Writers Conference