by Herbert Harris

I began my psychiatric training in 1990, the year that marked the start of a program called the “Decade of the Brain.” This was a well-funded, high-profile initiative to promote neuroscience research, and it succeeded spectacularly. New imaging techniques, molecular insights, and psychopharmacological discoveries transformed psychiatry into a vibrant biomedical science. The program brought thousands of careers, including my own, into the neurosciences.

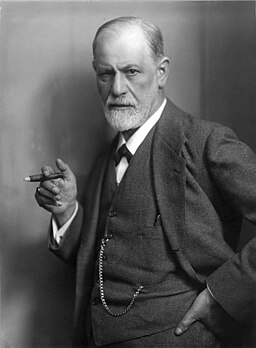

Despite its progress, the Decade of the Brain also widened an existing rift. This was the large gap between the psychoanalytic tradition and the biological sciences. The divide wasn’t new. Freud started with neurology but shifted to psychoanalysis when the brain sciences of his time couldn’t fully explain the complexities of the mind. For the first half of the 20th century, psychoanalysis was the main way to understand mental illness. Then, in the 1950s, new psychiatric drugs appeared: chlorpromazine for psychosis, lithium for mood disorders, and antidepressants for depression. For the first time, it seemed possible to treat mental illness by directly targeting the brain, rather than long-term therapy or institutional care.

By the time I was a resident, these diverging traditions had opened into a chasm. On one side was biological psychiatry, focused on neurotransmitters, neuroimaging, and cognitive-behavioral treatments, with outcomes that could be measured and tested. On the other side were psychoanalysis and its branches: attachment theory, object relations, and the investigation of unconscious conflicts through language, narrative, and symbolism. They had become separate languages, spoken within distinct professional communities, each wary of the other. There were occasional efforts at rapprochement, but little sustainable progress. By the end of the Decade of the Brain, reconciliation seemed almost impossible. I was fortunate to be in a training program that had a research track, allowing me to work in a lab, but I also had mentors who were distinguished analysts. It was like being in two different residencies.

Both have proven valuable over the years, but I never expected them to converge. However, today, circumstances appear to be shifting. A merging of neurobiology, computational neuroscience, and neuroimaging has created a new paradigm: active inference. For the first time, we can start to identify strong links between analytic models of the mind and biological models of the brain.

At its core, active inference is a theory that views the brain as a prediction machine. The brain doesn’t just react to incoming data; it continuously makes predictions about what will happen next, compares those predictions to the incoming signals, and updates its models as needed. When expectations are broken, the brain feels “surprise” and works to minimize it. You can think of surprise minimization as the brain’s fundamental goal, similar to how Freud once described drives or libido.

A key idea is the prior, which informally refers to a probabilistic expectation shaped by past experience. These priors help us navigate the world effectively when future events resemble what has happened before. However, priors can also bias perception. Some priors are more resistant to change than others, depending on their level of confidence: how strongly the brain trusts them compared to new data. The more confident the prior, the more difficult it is to update. This concept is particularly important when considering how early experiences influence long-lasting self-models.

To understand the conscious mind, we should start with interoception, the brain’s monitoring of the body. Much of this system developed as rapid, automatic control loops—regulating heart rate, blood pressure, and digestion. Few of these signals reach the higher cortex, but when they do, we experience them as moods, drives, and affects. This partially insulated layer of bodily control, which occasionally intrudes into conscious life, bears more than a passing resemblance to Freud’s early topographical model of the unconscious.

Furthermore, evolution has equipped us with the ability for second-order modeling. We can create models not only of the external world and our internal states but also of how others perceive us. Humans are deeply social; we constantly infer what others are thinking by interpreting cues from gestures, tone, and ultimately language. These recursive models, or models of models, form the basis of self-consciousness and free agency. In a recent publication, I referred to this framework as active intersubjective inference (AISI), highlighting the importance of relationships in shaping selfhood.

In general, psychoanalytic theories focus on early childhood experiences to explain dysfunctional patterns seen in adulthood. Other central concepts include the unconscious mind, psychological defense mechanisms, and transference. Each can be understood in terms of active inference.

Freud saw transference—the repetition of early relational patterns in the analytic encounter—as the heart of psychoanalytic therapy. He argued that the patient’s relationship with the analyst became the arena where the unconscious revealed itself, and where change could take place. Since Freud, transference has remained a central theme of analytic psychology.

From an AISI perspective, transference can be understood as the persistence of rigid priors about how others perceive us. Therapy works by loosening the precision weighting of these priors, enhancing the brain’s plasticity so that new relational patterns can be encoded. In effect, the analytic situation creates the conditions for predictive self-models to be revised.

The unconscious, too, takes on new clarity when viewed through active inference. It is not only a matter of anatomical compartmentalization—some information reaching the cortex, some not—but also of functional regulation. Predictive modeling is hierarchical, with constant top-down regulation of what enters awareness. Information can be perceived, processed, and acted on without ever reaching regions involved in self-consciousness. This explains how unconscious material can shape behavior while remaining inaccessible to reflection.

Projection and splitting, classic defenses, also make sense within this framework. A person who cannot tolerate feelings of envy may “project” them onto others, perceiving rivals as envious rather than recognizing envy within themselves. Splitting—the division of people or oneself into “all good” or “all bad”—reflects a failure to integrate conflicting self-models, leading to rigid, compartmentalized predictions. Both defenses highlight the fluidity of personal identity, which is never fixed but constantly negotiated. AISI helps us see defenses not as mysterious mechanisms but as strategies for reducing prediction error, sometimes sacrificing adaptability.

Over the last half-century, psychoanalysis itself has evolved along different paths. Two of the most influential schools are object relations theory and self-psychology.

Object relations theory emphasizes how early relationships with caregivers (“objects”) shape enduring mental models. These internalized relationships persist into adult life and strongly influence how we relate to others. From the perspective of active inference, these are simply early second-order self-models, predictions about how others will see and respond to us, that continue to guide behavior long after childhood.

Self-psychology, developed by Heinz Kohut, emphasizes how these self-models can be fragile or incomplete when early caregivers fail to provide consistent empathy and support. Such gaps create vulnerabilities that carry into adulthood. People with incomplete self-models often experience constant “error signals” and tend to manipulate others to get what is missing: attention, praise, validation, or control. Kohut introduced the concept of the selfobject, a person seen not as separate but as part of the self, which is crucial for maintaining self-cohesion. Today, selfobjects can be viewed as external sources for predictive self-models.

Both frameworks offer a natural connection to AISI: they describe lasting models of self and other, shaped by early experiences, that influence how we perceive and predict social interactions. Where psychoanalysis discussed object relations and selfobjects, neuroscience now refers to priors, precision weighting, and recursive inference.

To better illustrate how analytic theory and AISI are compatible, a specific example is helpful. Imagine a child raised by a father who is emotionally absent and a mother whose love is conditional, given only when the child excels. There is little empathic attunement: no one reflects the child’s daily joys and fears, and no one affirms his need simply to be. Instead, he learns that only performance garners recognition.

As an adult, this person seems confident, even grandiose. He talks about destined greatness, wealth, and power as if they are guaranteed. However, beneath the surface, he is vulnerable. When he receives a lot of praise, he feels alive. When admiration lessens, he responds with rage or retreats into emptiness. His relationships are unstable—partners are initially idealized but then devalued. Therapies that only address behavior or thoughts might help manage symptoms but don’t reach the deeper wound.

A psychodynamic approach is quite different. Instead of confronting his grandiosity, the therapist reflects his desire to be seen and acknowledges the unmet need for an idealized other. Over time, these responses reduce his rage, and he begins to tolerate frustration without falling apart. His predictive self-model, “I must be admired or I will collapse,” gradually becomes less rigid. He gains the ability to revise his expectations, integrate different parts of his identity, and develop more stable relationships.

In the language of self psychology, this therapeutic work addresses unmet selfobject needs, mirroring, and idealization that were absent in childhood. In the language of AISI, it enhances the plasticity of second-order self-models, allowing them to update in the face of new relational evidence.

The narcissism story illustrates how modern psychoanalysis and neuroscience can engage in dialogue. Where Kohut discussed selfobjects and mirroring, we now refer to recursive inference and precision-weighted priors. Where Freud mentioned transference, we can now discuss enhancing neuroplasticity within predictive modeling.

This new framework does more than just improve old ideas. It opens up possibilities for empirical tools, neuroimaging, computational modeling, and even simulations of predictive circuits—to be used in studying psychodynamic phenomena. We can start to test how unconscious processes work, how defenses form, and how therapeutic relationships change the brain. Most importantly, we can develop and test novel, psychodynamically-informed interventions.

If this integration succeeds, we may arrive at a framework that unites brain and mind. Such a framework would honor the depth of unconscious life while remaining open to scientific validation. It would recognize that the self is not a solitary entity but an emergent property of intersubjective inference, how we regulate ourselves, how we imagine others see us, and how we strive, always, to minimize the surprises of existence.

***

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.