by Herbert Harris

Many years ago, I began a meditation practice, sparked by curiosity and vague, middle-aged worries about stress and blood pressure. To my surprise, it quickly became a regular part of my life. I restlessly explored many forms of meditation and meditation groups, eventually coming to the San Francisco Zen Center. Before long, I found myself seated on a black cushion in the meditation hall each morning at 5:30. Twenty years later, and 2,500 miles away, I have a much more relaxed schedule, but I am still at it.

What is it like to meditate? This is a question I am constantly asked. Would a philosopher or scientist say there’s a distinct state of consciousness with its own special qualia? I don’t know. Maybe I’ve been doing it wrong, but meditation has never given me an experience that I would call altered consciousness. I’ve come to think the more interesting question is not what meditation feels like moment to moment, but what it is like to be a meditator, to live a life punctuated by these quiet, unremarkable moments of sitting still.

There are many ways our minds can store the details of our experience. We put facts and figures in one place, sensory experiences in another, and skills and procedures in yet another. There is a special kind of memory, called episodic memory, that holds not just the information about an event, but also a sense of our being there. Recalling episodic memories gives us a faint sense of time travel. These are the memories we can reinhabit. We remember a beach vacation as if we can feel the warm sand between our toes, hear the gulls above, and sense the light breeze on our skin. They have a lived-through quality, a presence that feels like “me.”

I have a torrent of episodic memories from my time in San Francisco, where I had just started a new job. I felt like a tourist; every street, every café, every meeting at the new company introduced a parade of unfamiliar faces. My memory was overloaded with experiences and sensations. It felt like my life had entered a new incarnation, complete with a new cast of characters I had to learn. As I stepped into a new role, I became, to some extent, a different person as I adapted to meet new duties and responsibilities. I was surrounded by people who each had hopes and expectations that I would be a good employee, a respectable colleague, and a friend. These hopes and expectations exerted palpable influences on my sense of self.

In the meditation hall, expectations were few. Read more »

Daniel Goleman’s

Daniel Goleman’s

Barring that reality, and knowing this would be an ongoing, lifelong issue, I got a tattoo on my Visa-paying forearm to remind myself that my actions affect the entire world. I borrowed Matisse’s

Barring that reality, and knowing this would be an ongoing, lifelong issue, I got a tattoo on my Visa-paying forearm to remind myself that my actions affect the entire world. I borrowed Matisse’s

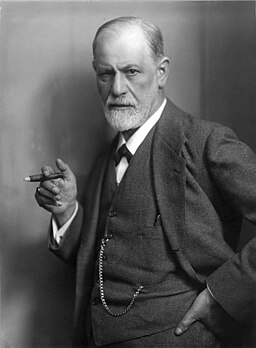

Our expectations sculpt neural activity, causing our brains to represent the outcomes of our actions as we expect them to unfold. This is consistent with a growing psychological literature suggesting that our experience of our actions is biased towards what we expect. —

Our expectations sculpt neural activity, causing our brains to represent the outcomes of our actions as we expect them to unfold. This is consistent with a growing psychological literature suggesting that our experience of our actions is biased towards what we expect. —