by Ashutosh Jogalekar

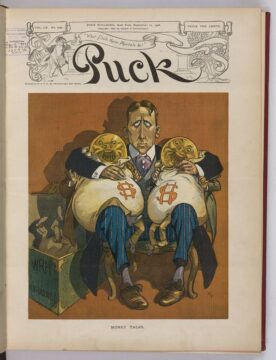

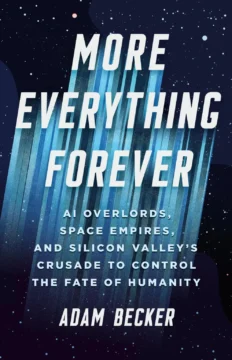

There has long been a temptation in science to imagine one system that can explain everything. For a while, that dream belonged to physics, whose practitioners, armed with a handful of equations, could describe the orbits of planets and the spin of electrons. In recent years, the torch has been seized by artificial intelligence. With enough data, we are told, the machine will learn the world. If this sounds like a passing of the crown, it has also become, in a curious way, a rivalry. Like the cinematic conflict between vampires and werewolves in the Underworld franchise, AI and physics have been cast as two immortal powers fighting for dominion over knowledge. AI enthusiasts claim that the laws of nature will simply fall out of sufficiently large data sets. Physicists counter that data without principle is merely glorified curve-fitting.

There has long been a temptation in science to imagine one system that can explain everything. For a while, that dream belonged to physics, whose practitioners, armed with a handful of equations, could describe the orbits of planets and the spin of electrons. In recent years, the torch has been seized by artificial intelligence. With enough data, we are told, the machine will learn the world. If this sounds like a passing of the crown, it has also become, in a curious way, a rivalry. Like the cinematic conflict between vampires and werewolves in the Underworld franchise, AI and physics have been cast as two immortal powers fighting for dominion over knowledge. AI enthusiasts claim that the laws of nature will simply fall out of sufficiently large data sets. Physicists counter that data without principle is merely glorified curve-fitting.

A recent experiment brought this tension into sharp relief. Researchers trained an AI model on the motions of the planets and found that it could predict their positions with exquisite precision. Yet when they looked inside the model, it had discovered no sign of Newton’s law of gravitation — no trace of the famous inverse-square relation that binds the solar system together. The machine had mastered the music of the spheres but not the score. It had memorized the universe, not understood it.

This distinction between reproducing a pattern and understanding its cause may sound philosophical, but it has real consequences. Nowhere is that clearer than in the difficult art of discovering new drugs.

Every effective drug is, at heart, a tiny piece of molecular architecture. Most are small organic molecules that perform their work by binding to a protein in the body, often one that is overactive or misshapen in disease. The drug’s role is to fit into a cavity in that protein, like a key slipping into a lock, and alter its function.

Finding such a key, however, is far from easy. A drug must not only fit snugly in its target but must also reach it, survive long enough to act, and leave the body without causing harm. These competing demands make drug discovery one of the most intricate intellectual endeavors humans have attempted. For centuries, we relied on accident and observation. Willow bark yielded aspirin; cinchona bark gave us quinine. Then, as chemistry, molecular biology, and computing matured in the latter half of the twentieth century, the process became more deliberate. Once we could see the structure of a protein – thanks to x-ray crystallography – we could begin to design molecules that might bind to it. Read more »

In recent years chatbots powered by large language models have been slowing moving to the pulpit. Tools like

In recent years chatbots powered by large language models have been slowing moving to the pulpit. Tools like

Everyone grieves in their own way. For me, it meant sifting through the tangible remnants of my father’s life—everything he had written or signed. I endeavored to collect every fragment of his writing, no matter profound or mundane – be it verses from the Quran or a simple grocery list. I wanted each text to be a reminder that I could revisit in future. Among this cache was the last document he ever signed: a do-not-resuscitate directive. I have often wondered how his wishes might have evolved over the course of his life—especially when he had a heart attack when I was only six years old. Had the decision rested upon us, his children, what path would we have chosen? I do not have definitive answers, but pondering on this dilemma has given me questions that I now have to revisit years later in the form of improving ethical decision making at the end-of-life scenarios. To illustrate, consider Alice, a fifty-year-old woman who had an accident and is incapacitated. The physicians need to decide whether to resuscitate her or not. Ideally there is an

Everyone grieves in their own way. For me, it meant sifting through the tangible remnants of my father’s life—everything he had written or signed. I endeavored to collect every fragment of his writing, no matter profound or mundane – be it verses from the Quran or a simple grocery list. I wanted each text to be a reminder that I could revisit in future. Among this cache was the last document he ever signed: a do-not-resuscitate directive. I have often wondered how his wishes might have evolved over the course of his life—especially when he had a heart attack when I was only six years old. Had the decision rested upon us, his children, what path would we have chosen? I do not have definitive answers, but pondering on this dilemma has given me questions that I now have to revisit years later in the form of improving ethical decision making at the end-of-life scenarios. To illustrate, consider Alice, a fifty-year-old woman who had an accident and is incapacitated. The physicians need to decide whether to resuscitate her or not. Ideally there is an

When I think about AI, I think about poor Queen Elizabeth.

When I think about AI, I think about poor Queen Elizabeth. In October last year, Charles Oppenheimer and I wrote a

In October last year, Charles Oppenheimer and I wrote a