by David Kordahl

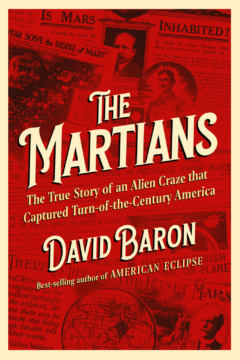

This article is a lightly edited transcript of a conversation with David Baron about his new book, The Martians: The True Story of an Alien Craze that Captured Turn-of-the-Century America. A video of this conversation is embedded below.

Intro and Percival Lowell Background (0:00)

Origins of the Canal Craze (6:39)

Gathering Evidence for the Canals (10:41)

Scientific Debate with Astronomers (14:02)

Thinking about “Outsider Scientists” (23:35)

Influence of Canals on Culture (27:45)

Reflections on Mars and the Future (32:33)

Intro and Percival Lowell Background

Today I’m speaking with David Baron, a seasoned science writer who has contributed to many major American journalism outlets, including the New York Times, the Washington Post, and the Wall Street Journal. He was a longtime science correspondent for NPR, and his TED Talk on the experience of solar eclipses has been viewed millions of times. His last book, American Eclipse, won the American Institute of Physics Science Writing Award in 2018. Today we’ll be discussing his new book, The Martians: The True Story of an Alien Craze that Captured Turn-of-the-Century America.

The “alien craze” in the subtitle of your book is the story of how, for about a decade at the beginning of the twentieth century, many people came to believe that the planet Mars held not only life, but a complex civilization. The person most responsible for popularizing this view as an established scientific fact was Percival Lowell. Lowell functions as a main character in your book.

I want to thank you for joining me today. At what point in your reporting for this book did it become clear that Lowell would function as a central figure in your story?

Oh, pretty much I knew that from the start. I first learned about the so-called “canals on Mars” from Carl Sagan, when I was in high school and watched the Cosmos series on PBS. On an episode about Mars, Sagan talked about this astronomer, Percival Lowell, who at the turn of the last century saw these weird lines on Mars that he believed were irrigation canals. It’s remembered as one of the great blunders in science, because it was an idea that really took off.

What actually surprised me was not that Lowell was my main character, but just how many other people got swept up in this craze—some of them quite prominent, famous scientists and inventors who totally believed that in fact there was the civilization on Mars. It was not just Percival Lowell. It was quite a collection of interesting characters. Read more »

There has long been a temptation in science to imagine one system that can explain everything. For a while, that dream belonged to physics, whose practitioners, armed with a handful of equations, could describe the orbits of planets and the spin of electrons. In recent years, the torch has been seized by artificial intelligence. With enough data, we are told, the machine will learn the world. If this sounds like a passing of the crown, it has also become, in a curious way, a rivalry. Like the cinematic conflict between vampires and werewolves in the Underworld franchise, AI and physics have been cast as two immortal powers fighting for dominion over knowledge. AI enthusiasts claim that the laws of nature will simply fall out of sufficiently large data sets. Physicists counter that data without principle is merely glorified curve-fitting.

There has long been a temptation in science to imagine one system that can explain everything. For a while, that dream belonged to physics, whose practitioners, armed with a handful of equations, could describe the orbits of planets and the spin of electrons. In recent years, the torch has been seized by artificial intelligence. With enough data, we are told, the machine will learn the world. If this sounds like a passing of the crown, it has also become, in a curious way, a rivalry. Like the cinematic conflict between vampires and werewolves in the Underworld franchise, AI and physics have been cast as two immortal powers fighting for dominion over knowledge. AI enthusiasts claim that the laws of nature will simply fall out of sufficiently large data sets. Physicists counter that data without principle is merely glorified curve-fitting.

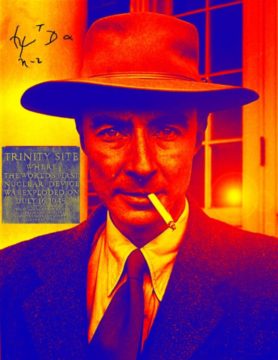

The photograph beside this text shows two men standing side by side, both scientific celebrities, both Nobel prizewinners, both of them well-known and well-loved by the American public in 1932, when

The photograph beside this text shows two men standing side by side, both scientific celebrities, both Nobel prizewinners, both of them well-known and well-loved by the American public in 1932, when

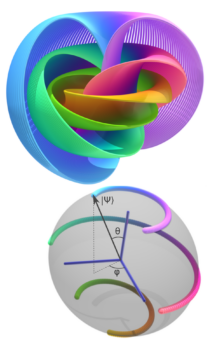

Physicists writing books for the public have faced a longstanding challenge. Either they can write purely popular accounts that explain physics through metaphors and pop culture analogies but then risk oversimplifying key concepts, or they can get into a great deal of technical detail and risk making the book opaque to most readers without specialized training. All scientists face this challenge, but for physicists it’s particularly acute because of the mathematical nature of their field. Especially if you want to explain the two towering achievements of physics, quantum mechanics and general relativity, you can’t really get away from the math. It seems that physicists are stuck between a rock and a hard place: include math and, as the popular belief goes, every equation risks cutting their readership by half or, exclude math and deprive readers of a deeper understanding. The big question for a physicist who wants to communicate the great ideas of physics to a lay audience without entirely skipping the technical detail thus is, is there a middle ground?

Physicists writing books for the public have faced a longstanding challenge. Either they can write purely popular accounts that explain physics through metaphors and pop culture analogies but then risk oversimplifying key concepts, or they can get into a great deal of technical detail and risk making the book opaque to most readers without specialized training. All scientists face this challenge, but for physicists it’s particularly acute because of the mathematical nature of their field. Especially if you want to explain the two towering achievements of physics, quantum mechanics and general relativity, you can’t really get away from the math. It seems that physicists are stuck between a rock and a hard place: include math and, as the popular belief goes, every equation risks cutting their readership by half or, exclude math and deprive readers of a deeper understanding. The big question for a physicist who wants to communicate the great ideas of physics to a lay audience without entirely skipping the technical detail thus is, is there a middle ground?