by Marie Snyder

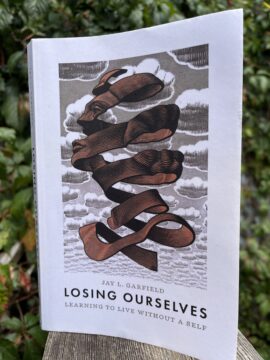

We’re living at a time when the glorification of independence and individualism is harming the world and others in it, as well as leading to an epidemic of loneliness. According to Jay Garfield, the root of suffering is in our self-alienation, and one symptom of our alienation is clinging to the notion that we are selves. “We are wired to misunderstand our own mode of existence,” he writes in his brief yet substantial 2022 book, Losing Ourselves: Learning to Live Without a Self.

We’re living at a time when the glorification of independence and individualism is harming the world and others in it, as well as leading to an epidemic of loneliness. According to Jay Garfield, the root of suffering is in our self-alienation, and one symptom of our alienation is clinging to the notion that we are selves. “We are wired to misunderstand our own mode of existence,” he writes in his brief yet substantial 2022 book, Losing Ourselves: Learning to Live Without a Self.

Garfield traces arguments against the existence of a self primarily through 7th century Indian Buddhist scholar Candrakīrti and 18th century Scottish philosopher David Hume, and explores where many other philosophers hit or miss the mark along the way. The book is a surprisingly accessible read about a complex topic with perhaps the exception of a couple more in-depth chapters that develop arguments to further his conclusion: you don’t have a self, and that’s a good thing.

Garfield starts with the idea of self from ancient India: the ātman is at the core of being. A distinct self feels necessary to understand our continuity of consciousness over time (diachronic identity) and our sense of identity at a single time (synchronic identity). A self gives us a way to explain our memory and allows for a sense of just retribution when we’re wronged. We feel a unity of self to the extent that it’s hard to imagine it’s not so.

However, Garfield argues that feeling of having some manner of core self is an illusory cognitive construction. Hume claimed the idea isn’t merely false but gibberish, and Garfield calls it a “pernicious and incoherent delusion.” We cannot infer from a sense of self that there is a reality of self. Garfield asserts that, “We are nothing more than bundles of psychophysical processes–changing from moment to moment–who imagine ourselves to be more than that.” We are similar to the person we were yesterday and a decade ago because we’re causally related yet distinct. We share enough properties and social roles with ourselves to feel as if we’re the same over the years. That causal connectedness enables the memory of the past and anticipation of the future. Read more »