by Sherman J. Clark

There are many reasons, moral and prudential, not to be cruel. I would like to add another. Cruelty is bad for us—not just bad for those to whom we are cruel but also bad for those of us in whose name and for whose seeming benefit cruelty is committed. Consider our vast system of jails and prisons. Much has been said about the moral injustice of mass incarceration and about the staggering waste of human and financial resources it entails. My concern is different but connected: the cruelty we commit or tolerate also harms those of us on whose behalf it is carried out. It does so by stunting our growth.

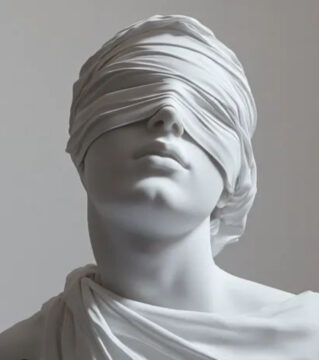

To sustain such cruelty, we must look away—cultivate a kind of blindness. We must also cultivate a kind of cognitive blurriness, accepting or tolerating tenuous explanations and justifications for what at some level we know is not OK. And in cultivating that blindness and blurriness, we may make ourselves less able to live well. It is hard to navigate the world and life well with your eyes half closed and your internal bullshit meter set to “comfort mode.”

We’ve gotten good at not seeing what’s done in our name. Nearly two million people are incarcerated in America’s prisons and jails. They endure overcrowding, violence, medical neglect, and conditions that international observers regularly condemn. We know this, dimly. The information is available, documented in reports and investigations and lawsuits. But we have developed an elaborate architecture of avoidance—geographic, psychological, linguistic—to keep this knowledge at arm’s length. We put prisons in the remote regions of our states, and prisoners in the remote regions of our minds. And we try not to think about it.

This turning away from the cruelty of mass incarceration is only one of many ways we hide from our indirect complicity in or connection to things that should trouble us. Prisons are just one particularly vivid example of ethical evasions that can dim our sight, cloud our minds, and thus in inhibit our ability to learn and growth and thrive. We perform similar gymnastics of avoidance everywhere: treating financial returns as somehow separate from their real-world origins; planning out cities so that the rich often need not even see the poor; ignoring the long-term consequences of political decisions. Each of these distances—financial, geographical, temporal—may appear natural, even inevitable, just how things work. But they’re architectures we’ve built, or at least maintain, to spare ourselves from seeing clearly.

Sometimes our potential complicity in cruelty is very indirect, and thus easier not to see. But still it looms. When we do something as simple as walk safely to a SoulCycle class in a gentrified neighborhood, what economic displacement, police misconduct, and incarceration were employed to “clean up” that part of town? Our walk to our workout may rest on a foundation we’d rather not examine. So, we don’t.

We may tell ourselves that this avoidance, this not thinking, protects us. But we may be wrong.

As a threshold matter, looking away doesn’t necessarily even avoid discomfort. Not looking takes work. Real, exhausting work. Watch yourself the next time prisons comes up in conversation. Notice the mental swerve, the quick change of subject, the hollow laugh. Feel the energy it takes to maintain the fiction that those people in those places have nothing to do with you. It’s like holding your breath—possible, but not sustainable, and it leaves you gasping.

Horror filmmakers understand this. The monster glimpsed in fragments terrifies more than the one shown in full light. The shadow at the edge of vision, the shape behind the door—these haunt us in part because we expend energy not quite seeing them. Our ethical monsters work the same way. The cruelties we half-know but won’t examine don’t disappear; they metastasize in the dark of our consciousness, requiring ever more elaborate defenses to keep at bay.

We could find out what is happening—the information is there. But not knowing feels safer. Except it isn’t. We find ourselves avoiding certain conversations, deflecting certain questions about justice and responsibility. The not-knowing spreads like a stain, touching everything it shouldn’t have to touch. The half-knowledge sits there, curdling ordinary pleasures. Every evasion brings with it a potentially poisoning price—the cost of hiding from what we know.

This is the first cost of looking away: we become people who must constantly manage what we allow ourselves to know. It’s exhausting. And it spreads.

And more than that—worse than that—we are blinding and stupefying ourselves in ways that diminish our own capacity to grow and thrive. The cost of looking away isn’t just emotional or even moral; it’s eudaimonic. We are making ourselves less capable of living fully human lives.

Returning to how we avoid facing the cruelty of mass incarceration, this is the paradox for those of us with consciences: we can’t bear to look at it. A sociopath might be perfectly capable of acknowledging the brutality of our prison system while eating breakfast, unmoved. But those of us who aspire to be good people—who need to see ourselves as decent, caring, moral—face an impossible choice. We can either look directly at the cruelty done in our name and feel the full weight of our complicity, or we can look away and pay the price in diminished capacity for growth and self-knowledge.

But the exhaustion of maintaining blindness is just the beginning. When we refuse to see the suffering of others, we don’t just lose information—we lose capacity.

To maintain our not-seeing about prisons, we must tell ourselves stories about the people inside them. They’re different. They’re worse. They chose this. But these stories require us to narrow our definition of humanity itself. We must forget that most of us have broken laws—speeding, drug use, tax fudges—and only some of us got caught. We must ignore how poverty, race, mental illness, and bad luck shape who ends up behind bars. We must pretend we would never make the mistakes that, given the right circumstances, we absolutely would make. This narrowing doesn’t stay contained. Once you’ve practiced shrinking your empathy to exclude “criminals,” it becomes easier to exclude others: the homeless, the addicted, the immigrant, anyone whose suffering might implicate you. Your world gets smaller, simpler, and less true.

And there’s something even more insidious happening. To justify our not-seeing, we become people who can’t afford to think clearly about cause and effect, about systems and responsibility, about the ways our lives interconnect with others’. If we really examined why someone might rob a store or sell drugs—really examined it, with all the contributing factors of education, opportunity, trauma, and circumstance—we might have to examine our own choices too. Better not to think that hard about anything.

We’re losing the chance to know ourselves. How we treat others—especially those we have power over—isn’t just about them. It’s information about who we are. But only if we are willing to look. Every society creates institutions that reveal its actual values, as opposed to its professed ones. Prisons are one of ours. They tell us things we need to know about ourselves: our capacity for cruelty, our tolerance for suffering, our willingness to sacrifice other humans for our comfort. This is information we desperately need. Not for self-flagellation, but for self-knowledge. How can we become better if we don’t know what we are?

The ancient Greeks carved “Know thyself” above the entrance to the Oracle at Delphi. They understood it as the threshold to wisdom—you couldn’t receive divine insight until you’d faced human truth. We’ve reversed this. We’ve made not-knowing ourselves a prerequisite for functioning in modern society. We’ve built entire systems to spare us from seeing what we do.

But the self-knowledge we’re avoiding isn’t optional if we want to grow. You can’t develop integrity while lying to yourself about what’s done in your name. You can’t cultivate wisdom while actively maintaining ignorance. You can’t become more fully human while denying the humanity of others. It is hard to find your way in life with dimmed vision and a blurred mind.

This is why I say the cost is eudaimonic, not just emotional or even moral. We’re not just becoming worse people; we’re becoming less capable of flourishing. The classical virtue ethicists understood that living well—not just feeling good but actually thriving as human beings—requires certain capacities: honesty, courage, practical wisdom, the ability to see clearly. Every time we look away from what’s done in our name, we atrophy these very capacities. We develop what seems like a protective skill—the ability to live adjacent to suffering without feeling it—but it’s actually a disability. It leaves us less capable of genuine relationship, honest self-reflection, and the kind of clear thinking that both good individual lives and good democracy require.

Let me be clear, there are ample ethical reasons to rethink our collective cruelty—in the context of mass incarceration and elsewhere. Our primary moral concern should no doubt be the harm we cause to the victims of our cruelty. And our primary prudential consideration should perhaps be the tragic waste. I am not suggesting, selfishly, that the main reason to avoid cruelty is that it stunts our own ethical growth. But I believe it does. And that provides an addition reason to rethink what we do and allow to be done in our name.

Looking—really looking—won’t be comfortable. But comfort is not our only goal. We also want to grow. And growth requires seeing clearly, especially when clarity hurts. The question isn’t whether we can afford to look at what we do to others. It’s whether we can afford not to. Because every day we practice not seeing, we become people who can’t see—not just the suffering of others, but the possibilities of ourselves.