by Jonathan Kujawa

With the end of daylight savings time, the long, dark nights of winter slump over the land. It is the season for cold nights, warm blankets, and reading good books with a nice cup of tea (or a dram of scotch, if you prefer). Unless, of course, you live in Hawaii or the southern hemisphere, in which case you’ll have to content yourself with reading in a convenient hammock.

Popular math books are a sub-sub-sub-genre of nonfiction, found at a local bookstore in the Nonfiction-Science-Math-“Math? For fun? Really? Ok, if you say so.” section. Even within that narrow span of the bookshelf, you’ll find there are a wide variety of popular math books. Some ambitiously try to give you a sense of deep, modern topics of research like the geometric Langlands program or statistical mechanics. Although I suspect those mainly succeed in giving Hawking’s “A Brief History of Time” and Piketty’s “Capital” a run in the category of many sold but few actually read. Other authors lean towards biography. While interesting and enjoyable reads, they are not often about math, per se. I’m looking forward to someday getting to Siobhan Roberts’ well-reviewed biographies of Coxeter and Conway. Both sound great! But such books necessarily can only hint at the amazing math their subjects have done.

Perhaps unavoidably, too many popular math books end up missing the mark. Trying to talk math without the technicalities, the authors are left leaning on old standbys like the irrationality of √ 2, Hilbert’s Hotel and the marvels of infinity, and picture friendly topics like fractals. It’s a bit like eating a big bowl of oatmeal: a whole lot of familiar filling with the occasional pleasant surprise mixed in. Not that I’m throwing stones! My house here at 3QD is built from its share of tired metaphors, mathematical and otherwise. Every person who writes about math knows the truism: every equation you include cuts your readership in half. But talking about math without, you know, writing down any math is darn hard. It’s like writing about music or poetry in strict essay form.

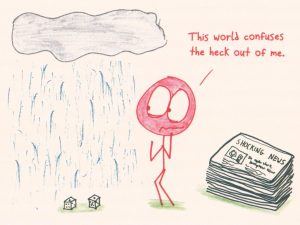

Certainly, math has a PR problem. Somehow string theory and cosmology, DNA and biology, economics and sociology, do better at capturing the public’s imagination. The beauty, excitement, fun, and wonder of mathematics rarely seems to break through. Perhaps because math tends to be of this world, but not in it. While it is unreasonably useful in explaining our reality, math ultimately lives only in the mind and can be hard to pin down and appreciate.

Every so often I come across a popular math book which genuinely excites me. It captures math on the page in the way I know it, and I’m happy to recommend the book to friends, family, and 3QD readers. The Godfather, of course, is Martin Gardner. A fellow Okie, Gardner did more than an army of high school math teachers to introduce people to the joy of mathematics. More recently, Matt Parker’s “Things to Make and Do in the Fourth Dimension” and Jordan Ellenberg’s “How Not to be Wrong” are two other books worth giving as gifts this winter. They both manage to capture the innate coolness of math by telling new tales (or old tales in new ways) in an interesting, accessible way.

These are the exception, though. While it is a golden age of math blogs, podcasts, youtube videos, and the like, it is still rare to find a book which I can widely recommend. This is why I was thrilled to hear Ben Orlin of “Math with Bad Drawings” blog fame had written a book! He earned a degree in math and then went on to teach at schools in Oakland, CA and Birmingham, UK. More recently, Ben is famous in the sub-sub-sub-genre of Internet-Blog-Math-Humor for sharing his insights on math, teaching, and life through his pen-and-ink drawings. I’ve regularly read his blog for years and more than once felt a pang of professional jealousy. His book was sure to be aces!

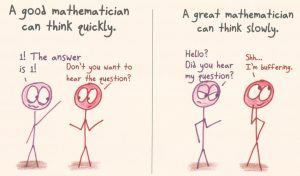

Ben’s book (also called “Math with Bad Drawings”) doesn’t disappoint. The math itself is mostly at the pre-calculus level and accessible to pretty much anyone. Nevertheless, it has enough clever twists and tidbits to keep even a jaded professional mathematician reading. Ben’s not-so-secret strategy is to avoid deep dives into subjects. He instead finds clever angles and revealing insights, all with generous doses of Mathematician’s Jokes [1] and drawings.

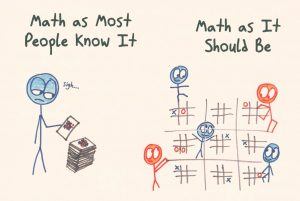

For example, every elementary school kid (and WOPR) knows tic-tac-toe is boring. It doesn’t take long for players to figure out a strategy which leads to endless tie games. This could have led Ben to drill down into game theory, NIM, von Neumann and John Nash, nuclear war and prisoner’s dilemmas. Instead, he veers into an interesting new direction to talk instead about the game of Ultimate tic-tac-toe played at the UC Berkeley math department. You play on a tic-tac-toe board’s worth of tic-tac-toe boards:

When one player marks a square on one of the small boards, the next player must mark a square on the small board in the corresponding position of the large board. So if I mark the middle of my small board, then you have to play the small board in the middle of the large board but, in turn, when you decide where to play you are also determining which board I must use next. This turns an easy game where the obvious move is the best move, to a next level game where you have to plan multiple moves ahead. With this as a launching point, Ben talks about the tension between too easy and too hard, and how much of the best math dances along this line. He also shows how slight variations to the rules of Ultimate tic-tac-toe can quickly lead to the trivial or the impossible.

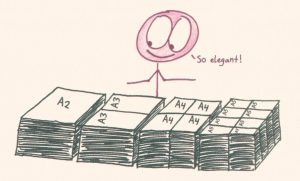

Another discussion centers on the irrationality of good ol’ √2. Rather than rolling out the standard proof that, indeed, the square root of two cannot be written as the ratio of two integers, Ben Orlin jumps and twists in an unexpected direction. He laments the fact the standard A4 sized paper he used while living in the UK has a length/width ratio maddeningly close to √2. What perverse individual would size paper so the ratio of its sides equals a number which is infamous for not being a ratio? I won’t spoil the surprise, but only hint that once you are told that a sheet of A3 cut in half is, by design, exactly two sheets of A4, and, likewise, one sheet of A4 equals two sheets of A5. Follow the math and the square root of two shall appear!

Another discussion centers on the irrationality of good ol’ √2. Rather than rolling out the standard proof that, indeed, the square root of two cannot be written as the ratio of two integers, Ben Orlin jumps and twists in an unexpected direction. He laments the fact the standard A4 sized paper he used while living in the UK has a length/width ratio maddeningly close to √2. What perverse individual would size paper so the ratio of its sides equals a number which is infamous for not being a ratio? I won’t spoil the surprise, but only hint that once you are told that a sheet of A3 cut in half is, by design, exactly two sheets of A4, and, likewise, one sheet of A4 equals two sheets of A5. Follow the math and the square root of two shall appear!

The book touches on a wide variety of topics. From sensible insurance to the craziness which is American healthcare, from voting and gerrymandering to why triangles are naturally strong while squares are fatally feeble. Throughout are overt and covert reassurances everyone can do and love math, regardless of “talent”. All and all, it makes a great gift for people who already like math, and especially for those who like math but just don’t know it yet. Or for your own enjoyable reading during these long, dark nights.

The title, of course, is tongue in cheek. I would tell you they are better than anything I could do, but that’s the faintest of praise. As my calculus students will testify, my “drawings” are an unholy mashup of impressionism and cubism consisting of floppy sombreros and lumpy potatoes meant to convey mathematical meaning about geometric shapes. Ben’s drawings are streets ahead of my meager efforts. There is a reason why I’m an algebraist.

[1] See also: Dad Jokes.

[2] All images from my copy of Ben Orlin’s “Math with Bad Drawings”.