by Laurie Sheck

1.

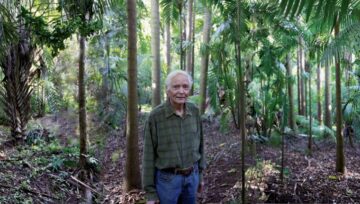

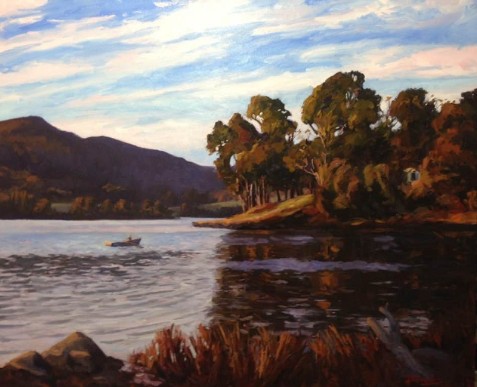

In the garden of the Maui home where the poet W.S. Merwin lived for the last forty years of his life, writing and translating poems, and restoring deforested land into a flourishing palm forest, there is a black stone marker engraved with his name and that of his wife, along with the four simple words “Here we were happy.” It is a remarkable story. Merwin first came to the island in 1975 to study with the Buddhist teacher Robert Aitken. Drawn to the land, he found at first three acres of a disused pineapple plantation where, with the help of friends, he built a house. Later, he purchased and tended fifteen acres more. Over the years, seedling by seedling, he planted his palm forest. At first, he wanted to plant only trees native to the island but found through experience the ecosystem had been so degraded they could no longer survive. The first 800 trees he planted died. After that, he focused on planting various endangered species of plants and trees. He planted one tree almost daily; by the time of his death, he had planted approximately 14,000 palm trees.

The history of the island is one of natural beauty severely harmed by human intervention. When the earliest settlers arrived, many of its trees were cut down to provide wood for the construction of whaling ships. Soon the land was further cleared for grazing cattle. Rats, mosquitoes and other life-forms foreign to the island were introduced. In 1876, the Hamakua Ditch Company began building a network of ditches and tunnels that diverted the rainwater from the central valley to newly cultivated sugar cane fields. The valley was starved of water. By 1917 nearly 130,000 acres of Maui had come under the ownership of sugar plantations and factories. Large numbers of the native population had died from infectious diseases brought to the island by Americans and Europeans. When the pineapple industry arrived, it further destroyed what was left of the native ecosystem.

2.

These are some of the life-forms that were lost: Acacia palm trees, sandalwood trees, many kinds of native land snails, damselflies, honeycreepers.

By the time of Merwin’s death, his plantings included 128 genera and 486 species. One ecosystem had been destroyed but another had begun to flourish.

3.

I first came upon Merwin’s poems in my early twenties. It interested me that he had turned from the lapidary early poems that drew notice from W.H. Auden, who picked Merwin’s first book for the Yale Series of Younger Poets, to something much starker, stripped down, alert to and pained by human hubris and error. By his 6th volume, The Lice, he had dropped punctuation. The poems were concerned with war, destruction, power, and the counterforces that make us of value as a species, and that make our planet a wondrous place. Read more »

“A clearly written and compelling account of the existential risks that highly advanced AI could pose to humanity.” — Ben Bernanke

“A clearly written and compelling account of the existential risks that highly advanced AI could pose to humanity.” — Ben Bernanke

Natalie Bakopoulos: Thank you so much, Philip, for starting this conversation, and for these wonderful observations and connections. You’re absolutely right, I was indeed playing with the idea of “beginnings.” “Here in Greece,” the narrator says, “the rivers rarely have a single source: They spring from the mountains at several places.” I also wanted to think about the arbitrariness of origin and a way of thinking about belonging that wasn’t necessarily about “roots”—but instead rhizomes, as Edouard Glissant, and others, might say.

Natalie Bakopoulos: Thank you so much, Philip, for starting this conversation, and for these wonderful observations and connections. You’re absolutely right, I was indeed playing with the idea of “beginnings.” “Here in Greece,” the narrator says, “the rivers rarely have a single source: They spring from the mountains at several places.” I also wanted to think about the arbitrariness of origin and a way of thinking about belonging that wasn’t necessarily about “roots”—but instead rhizomes, as Edouard Glissant, and others, might say.

The wealthy and powerful have always used the narrative to their advantage. The narrative defines them as superior in some way, and thus deserving of their power and wealth. In ancient times, they might be descended from the Gods, or at least favored by them or otherwise connected to them, perhaps through special communicative powers that granted them insights into the will of the Gods or God. In modern capitalist societies, that narrative promotes a fantasy of merit. You are rich and/or powerful because you are better. You are more civilized, better educated, more intelligent, or blessed with an exceptional work ethic. These narratives cast wealth and/or power as not only justifiable, but deserved.

The wealthy and powerful have always used the narrative to their advantage. The narrative defines them as superior in some way, and thus deserving of their power and wealth. In ancient times, they might be descended from the Gods, or at least favored by them or otherwise connected to them, perhaps through special communicative powers that granted them insights into the will of the Gods or God. In modern capitalist societies, that narrative promotes a fantasy of merit. You are rich and/or powerful because you are better. You are more civilized, better educated, more intelligent, or blessed with an exceptional work ethic. These narratives cast wealth and/or power as not only justifiable, but deserved.

In

In

In a recent essay,

In a recent essay,

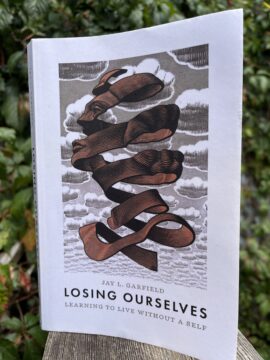

We’re living at a time when the glorification of independence and individualism is harming the world and others in it, as well as leading to an epidemic of loneliness. According to Jay Garfield, the root of suffering is in our self-alienation, and one symptom of our alienation is clinging to the notion that we are selves. “We are wired to misunderstand our own mode of existence,” he writes in his brief yet substantial 2022 book,

We’re living at a time when the glorification of independence and individualism is harming the world and others in it, as well as leading to an epidemic of loneliness. According to Jay Garfield, the root of suffering is in our self-alienation, and one symptom of our alienation is clinging to the notion that we are selves. “We are wired to misunderstand our own mode of existence,” he writes in his brief yet substantial 2022 book,