by Jochen Szangolies

We have entered a versioned world. A new release of a major AI model (GPT-5) triggers the subsequent release of new versions of articles variously hyping and disparaging the progress it represents. How does it stack up in benchmarks against earlier models? How well can it code? Can you feel the AGI (even more)? Will this take my job, or skip that step and directly declare war on its creators?

We are reminded, in each iteration of the cycle, of both the promises and perils of ongoing AI developments. For every article touting a supposed productivity increase, there is one warning against mass unemployment. Every voice decrying the still-unsolved fundamental problems of generative AI is matched by one breathlessly updating their priors for imminent human-equivalent AGI (or alternatively, increasing their ‘P(doom)’, the estimated likelihood that AI will kill us all). In their predictably incremental nature, they mirror the releases they chronicle: the miracle of AI progress is beginning to grow stale.

This article is itself, in parts at least, an iteration of an earlier one. My excuse for writing it is that I think the concerns raised there, of how AI threatens to diminish the meaning of human creativity, is still not quite appreciated in the right way. Mass production, copyright infringement, oversaturation: these are real issues, but fail to get to the heart of it.

Semantic Apocalypses

In a recent piece in reaction to the ‘Ghiblification’-trend, neuroscientist Erik Hoel has introduced the concept of a semantic apocalypse—roughly, the erosion of meaning through repetition on a cultural scale. By making Ghibli-art a readily available commodity, it looses its special nature, and becomes just so many pixels on a screen. On the individual level, we are very familiar with this sort of process: repeating a word over and over, it starts to loose its meaning, and becomes just a sequence of syllables—it sheds its semantic value, and is present only at a syntactic level, the symbol that is usually a transparent window onto whatever piece of the world it represents suddenly becoming opaque.

There is a connection, here, to the Heideggerian concepts of Vorhandenheit and Zuhandenheit—being present-at-hand as opposed to being ready-to-hand. A tool, such as a hammer, is ready-at-hand to the extent that it is available to be used as a hammer; but crucially, in its use, it becomes part and parcel of the instrumentarium with which we act in the world, and thus, is no longer present-at-hand as an object in the world. This both shapes the way we relate to the world (‘if all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail’) and hides elements of it from our direct apperception, creating what I called earlier an ‘absent absence’—a blind spot characterized not merely by not seeing something, but even failing to notice that there might be something to see.

This is what happens with a word, used as a symbol, upon repeating it: it looses its semantic character, thus we loose the ability to use it as a symbol—it is no longer ready-to-hand. Instead, it becomes present to us as a particular thing in the world, a certain collection of phonemes, present-to-hand in a way it wasn’t before. We now see the symbol itself, rather than the piece of the world it is directed at. There is a complementary relationship here: we either perceive the symbol’s meaning, at the expense of the symbol itself vanishing behind its use, or the symbol itself, now hiding the reality it previously uncovered.

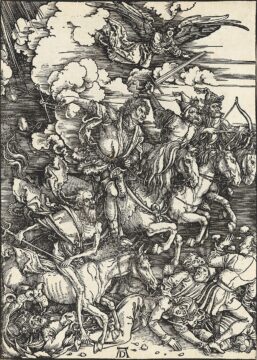

Hoel’s semantic apocalypse then refers to the same phenomenon happening on a society-wide level. Art that was precious and meaningful reduced to empty signifiers, mere husks of themselves, the beached hulls of ships once used to navigate the vast ocean of interconnected human experience. Robbed of their function, all that remains is their form. And with the ubiquity and ease of use of modern AI models, virtually any domain of intersubjective exchange—language, art, music, poetry—seems poised to be likewise hollowed out.

Against this, in a piece directly reacting to Hoel’s, psychiatrist, LessWrong-rationalist and co-architect of the ‘AI2027’-scenario Scott Alexander has argued that semantic apocalypses are really nothing new—they occur when the 1,000th sunset fails to wow us the same way the first one did, when audio recordings make the once-in-a-lifetime experience of hearing a particular piece performed by a particular artist for the first time obsolete, or when jet air travel brings even the furthest and most hallowed places within arms reach.

In the face of technological progress, erstwhile unimaginable wonders have routinely become commonplace, boring—even bothersome. Just imagine how we took the ancient dream of soaring through the air, above the clouds, under the direct light of the sun or in the face of the splendor of the night sky, and turned it into a commodified experience of frustration at delays, cramped seats, terrible food and sheer boredom. Perhaps this is just the price to pay for progress? And perhaps whatever we might loose, we are amply repaid by novel and heretofore scarcely conceived of wonders?

To his credit, Alexander does not succumb to such naive techno-optimism. He recognizes the ambivalence of wishing to preserve the singularity of any given experience while yet not wanting to forgo the amenities of technological progress. In this light, however, his attempt at mitigation seems somewhat puzzling: citing the examples of William Blake and G. K. Chesterton, he proposes that there might be a way to enjoy the 1,000th sunset like the first, that some form of exalted consciousness (he proposes mushrooms or meditation, or maybe just the right genetics) might stem the effects of oversaturation.

But, as Walter Benjamin recognized already 90 years ago, this must necessarily fall short. As argued in his 1935 essay The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, what is lost in such mass availability is what he calls the aura, the appearance of remoteness, no matter how close the work itself may be. It is thus a kind of pointing beyond itself, not exactly congruent with, but also not completely disjoint from the semantic dimension of the symbol. (Indeed, together with his later concept of Spur—‘trace’ or ‘track’—which characterizes the presence of the conditions of an artwork’s creation despite their absolute distance, the aura forms part of a similarly complementary pair as being ready-at-hand or present-to-hand, or the semantic and syntactic dimension of the symbol.) An important component of this aura is the singularity of the work of art: thus, keeping the aura while multiplying the work is a contradiction in terms.

In the end, both Hoel’s and Alexander’s pieces fall short of identifying the real threat of AI to art: it is not merely that the semantic dimension—the meaningfulness, the wonder of it all, the awe-inspiring presence—is eroded, but rather, that the reality of AI produced art threatens the conditions that make the production of meaningful art possible in the first place. AI art is inherently syntactic, in a very precise manner: it is produced by merely transforming that which pre-exists it, and is constitutionally incapable of yielding any genuine novelty. We are thus not witnessing a dilution of ‘meaningful’ art by mechanical means, but a wholesale replacement by a cargo-cult construct that goes through all the machinations of art without ever getting its animating principle. And in setting up this system, we risk losing sight of that principle, without even noticing—creating a blind spot, an absent absence, a lack we fail to recognize.

The Creative Spark

The above requires a fair bit of unpacking. As long as there have been proposals of mechanized versions of ourselves, from medieval automata to present-day large language models, there have been arguments that such entities must lack a certain something, an animating spark, a vital principle, a soul. This ‘theological objection’, as Alan Turing called it in his landmark paper Computing Machinery and Intelligence, whence we get the test named after its author, is generally dismissed as mere special pleading—and rightly so. There is not, to the best of my knowledge, anything ‘special’ about humans that couldn’t be replicated in a different substrate, such as silicon.

But that is a far cry from claiming that AI models of the kind in development today could, even in principle, possess faculties equal to that of human beings. And here, there is a simple matter of fact that such entities can’t possess genuine creativity: as computer programs, all of their responses are a deterministic function of their inputs (no matter possible pseudo-randomness, which itself is deterministically dependent on a particular seed value). This entails that they never create novel information: all they can ever hope to do is to transform the information they’ve been given.

This point, first raised by science fiction author Ted Chiang, is essentially uncontroversial, but can be surprisingly hard to get across. Novelty can only be created where the end-product isn’t reducible to the prior data—otherwise, that end-product is really just a mixed, or translated, form of this data. And no deterministic process can accomplish this: it will always be possible to freely translate between input and output of such processes. Computations, however, are deterministic processes. Thus, no computation can produce genuine novelty.

Against this, one might hold, as Erik Hoel indeed does, that humans typically aren’t all that original, either. But that’s to miss the point: even if in any typical piece of art, most of the information present may be traceable to prior influences, there is some addition to the literal substance of the world—some novel choices, as Chiang phrases this (perhaps unfortunately). In an AI creation, there is none of that—and the difference between nothing and something is infinite.

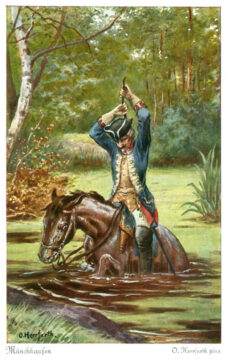

Of course, one might take the hardline view that even humans never make any genuine choices—whatever you do today is fixed by the past and the laws of physics, and that’s just that. I remain unconvinced by this story. We are viewing the world through a lens of theories, and that is to view it through a lens of mechanical explanation—any theory we can write down, we can simulate on a computer. That’s in fact part of may daily bread and butter. And through this lens, anything will inevitably seem algorithmical: hence, incapable of producing novelty. Every explanation will ultimately hit the Münchhausen trilemma: either collapse to circularity, spiral into infinite regress, or hit the dead end of bare postulation.

But just because that is a feature of our theories doesn’t entail that it’s a characteristic of the world, as well! We might do well to show some epistemic humility: after all, nobody has ever guaranteed us that the ambit of theoretical explanation coincides with the boundaries of the possible. Thus, to the degree that there is any information at all in the world, there must be a lacuna in all our theories that fails to account for how this information came into being—a black box postulating an unexplained creatio ex nihilo, or quantum randomness, or a first mover getting things going. (See also the discussion in these previous essays.)

If there thus is a mechanism for creating novel information, then it is at least possible for human beings (and other entities) to avail ourselves thereof. But not so for LLMs: their very construction curtails this option.

This is then the creative spark: not something mysterious and vague, but something well defined, and even fully quantifiable. It is this that provides the semantic dimension to works of art, that makes them more than their mere physical presence: that they are a testament to the novel choices made in their creation. And it is this we stand to loose when we cede ground to AI slop.

Navigating The Labyrinth

Still, it might be difficult to appreciate what, actually, is lost when art is replaced with the hollow shells of AI products. Because art, as such, is just the tip of the iceberg: it is that part of reality that makes itself known to us within our symbolic forms of communication. We make choices unique to each of us every day, and by making these choices, we literally add to the substance of the world: we create information that was not there before. Art is a way to give form to some small part of these choices and communicate them to one another, even if imperfectly. Explicit modes of communication—explanations and justifications—fail to account for this for the same reason theories do, but with art, we can at least point beyond the symbolic medium at the reality that can’t be grasped directly. It is a way to share the unshareable, to invite another to partake in the unique process of creation that allows you to navigate the vagaries of the world.

Consider the task of finding your way through a labyrinth. At each juncture, you must choose which way to go; and how you choose determines whether you make it through. Now consider a robot programmed with an algorithm for making these choices: its performance might superficially equal yours, but it has no contact with the world beyond. In fact, it might follow the same course, even if the labyrinth weren’t there. There is no connection to the real, no groping around and finding one’s way, just the deterministic certainty of the programming. Art is the ultimate expression of human agency, the reality of choice in the world, and AI art is its exact negation.

The semantic apocalypse is only a symptom: the real issue is the loss of agency, or the substitution of pseudo-agency. But like in the labyrinth-example, this is hard to see—the surface-level phenomena remain the same. What is lost, in a way, is the spectre of unactualized possibilities: where we could have gone another way, a robot following its programming only ever had one course available. A world of branching potentiality is collapsed to a single line, carrying us onward along the inevitable march to the future. Rather than individuals acting in the world, we become a faceless mass swept up in the narrative of progress, guided on rails laid for us by forces we can scarcely comprehend. There Is No Alternative, indeed.

Benjamin, through keen observation of his time, already noticed the inherently fascist dimension of a mass-produced aesthetics that grinds up individual choice within the wheels of (supposed) progress. With AI art, this development comes full circle: rather than merely diluting the creative spark, the role of individual agency, it is abolished entirely. But even if forces conspire to suppress the very notion, we still have choice: and we can only be deprived thereof by surrendering it voluntarily. If we do not want to make an absent absence of human agency, ushering in a humanity 2.0 dispossessed of choice and will, we should resist the false, frictionless facade of AI art.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.