by Jochen Szangolies

The principal argument of the previous column was that without the possibility of making genuine choices, no AI will ever be capable of originating anything truly novel (a line of reasoning first proposed by science fiction author Ted Chiang). As algorithmic systems, they can transform information they’re given, but any supposed ‘creation’ is directly reducible to this initial data. Humans, in contrast, are capable of originating information—their artistic output is not just a function of the input. We make genuine choices: in writing this sentence, I have multiple options for how to complete it, and make manifest one while every other remains in the shadow of mere possibility.

This is of course a controversial proposition: just witness this recent video of physicist Sabine Hossenfelder making the case for free will being an illusion. In particular, she holds that “the uncomfortable truth that science gives us is that human behavior is predetermined, except for the occasional quantum random jump”. I think this significantly overstates the case, in a way that ultimately rests on a deep, but widespread misunderstanding of what science can ‘give us’—and more importantly, what it can’t.

Before I make my argument, however, I feel the need to address an issue peculiar to the debate on free will, namely, that typically those on the ‘illusionist’ side of the debate consider those taking a different stance to do so coming from a place of romantic idealization. The charge seems to be that there is a deep-seated need to feel special, to be in control, to have authorship over one’s own fate, and that hence every argument in favor of the possibility of free will is inherently suspect. I think this is a bad move. First of all, it poisons the well: any opposing stance is tainted by emotional need—just a comforting story its proponents tell themselves to prop up their fragile selves. (Hossenfelder herself describes struggling with the realization of having no free will.)

But more than that, I just don’t think it’s true—disbelief in free will can certainly be as comforting, if not more so. After all, if I couldn’t have done otherwise, I couldn’t have done better—I did, literally, my best, with everything and always. No point beating myself up about it afterwards. As Albert Einstein put it in The World as I See It:

Schopenhauer’s saying, that ‘a man can do as he will, but not will as he will’, has been an inspiration to me since my youth up, and a continual consolation and unfailing well-spring of patience in the face of the hardships of life, my own and others’. This feeling mercifully mitigates the sense of responsibility which so easily becomes paralysing, and it prevents us from taking ourselves and other people too seriously […].

Moreover, the (often implicit) proposition that life is only worth living if one has control over its course is itself dodgy. We value plenty of things where we have no such influence: the ending of the book you’re reading or the film you’re watching has been determined perhaps years ago; the rails on which the roller coaster rides take forever the same course. Yet such activities are perfectly valuable, even enjoyable. So why should it be an ‘uncomfortable truth’ for life to work the same way?

Thus, if free will proponents can be accused of emotional reasons grounding their stance, then so, at minimum, can the illusionists (and putting my cards on the table here, my own intuition has been rather more aligned with Einstein than with Hossenfelder in the past). There is thus little value in such finger pointing. So which way should the chips fall, and how can we decide?

A Critique Of Theoretical Reason

I have given the matter some thought previously here on 3 Quarks Daily, see here and here. But I think I’ve since cleared up my argument enough to warrant a streamlined presentation, which is what I will attempt here. In a nutshell, the core insight of my argument is that no possible theory can account for novel information coming into being. To the extent that information thus does come into being, there must be a ‘blind spot’ to any possible theory. Any supposed argument against free will, ultimately, then just points out the existence of this blind spot—by effectively highlighting the Münchhausen trilemma that every explanation ultimately terminates in circularity, infinite regress, or mere postulation. The error here is to take the limits of theory for the limits of the world—that what we can’t grasp using theoretical models can’t exist. If there is any ‘human chauvinism’ in the debate, then, it is here: what cannot be explained cannot be. But the world has little cause to care for human sensibilities.

We have reason to believe that information does indeed enter the world—be it at the beginning, or in the random motions of elementary particles. Information that was not there before—which path the photon takes in the interferometer—now is. Any attempt at producing a theory that takes account of how this new information emerges is doomed to fail. In a sense, this is just the price to be paid for explanation to be possible at all: exactly because every explanation is a finite sequence of well-defined steps—an algorithm, in other words—it is impossible to extend its remit to the origin of information.

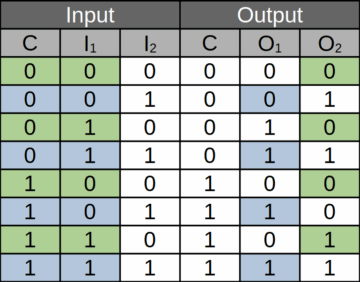

Every theory starts with some basic information—in the formal, mathematical case, a set of axioms—and then derives consequences from these by means of (finite) operations. Now, if these operations are truth preserving—that is, if your conclusions are true given that the premises are—then they are also information-preserving (or at least, information non-creating—it is possible to ‘throw away’ information). One way to see this is to consider the so-called Fredkin gate, a logical operation described by physicist Edward Fredkin in 1982. It takes three bits as input, and produces a three-bit output. The first bit is the control: its value dictates what happens to the other two bits. (In the output, it is simply copied.) If the control is 0, then the other two bits are also just copied; if it is 1, the values of the bits are swapped. Importantly, knowing the Fredkin gate’s output entails knowing its input: you still have full information about the prior state—but nothing more.

Surprisingly, all of the operations of elementary logic can be realized by means of the Fredkin gate. If the second input bit is 0, then the second output bit will hold the value of the logical operation ‘control AND first input’; if it is 1, then the first output corresponds to ‘control OR first input’. Using this, arbitrary logical operations can be performed by means of Fredkin gates, and the information at each step always allows to fully reconstruct the initial information. Nothing is lost, but also, crucially, nothing is gained. Nothing we can do in deriving consequences from premises allows to describe the generation of information. There is no theory of genuine novelty, and there can never be one, simply by virtue of what a theory is.

Nevertheless, it is instructive to think a little on what a ‘theory’ of information creation could look like. One option is to simply postulate it: to add a black box—an ‘oracle’ in the theory of computation—to the theory that comes up with novel bits of data. This is, essentially, the route taken in quantum mechanics: ordinarily, a quantum state evolves in just such an information preserving manner, but upon measurement, a random event is triggered and one path taken to the exclusion of all others. In the Münchhausen trilemma, this is the ‘dogmatic’ option: what you need is simply postulated.

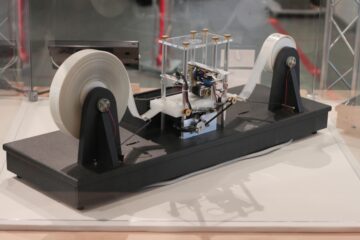

But suppose you aren’t satisfied with this sort of explanation: you want to know what goes on in the box. How does it manage to draw a shiny new bit from the ether? As we have seen, no finite sequence of operations can do so. But how about an infinite one? Consider the following device: a machine that takes an input on a ‘tape’ of infinite length, and performs an operation (reading, writing, changing its state) based on its state and the state of the part of the tape it reads. Thus far, this is just an ordinary Turing machine, a theoretical model of a computer. But now suppose that with every operation, the machine speeds up, completing it in half the time of the previous step. A little algebra then shows that if the first operation took one minute, after two minutes, it will have completed infinitely many steps.

It turns out that such a machine is capable of producing novel information—randomness, in the formal mathematical sense. Essentially, this is because it can solve the halting problem—the question of whether an ordinary Turing machine, after receiving a particular input, ever stops and produces an output (or whether a program gets trapped in an infinite loop). Thanks to this, it can compute the halting probability—a number that quantifies, given an arbitrary program, how likely it is for a Turing machine to halt. But this number contains, in a sense, an infinite amount of information: there is no finite set of data such that the number could be computed using finitely many steps of ordinary logic (e.g. Fredkin operations). That is, given, say, the first n bits of the halting probability’s binary representation, there is no way to derive the next bit; and this yields a mathematically stringent definition of randomness (known as algorithmic randomness).

Thus, such a ‘Zeno machine’ can generate novel information. It does so by taking the second option in the Münchhausen trilemma: it essentially traverses an infinite regress, updating its own state based on its own prior state infinitely often. The third option, circularity, is also feasible: we take the output of the black box, copy it, and go back in time to feed it back into the box. (The astrophysicist J. Richard Gott III has proposed that this may account for the origin of the universe, and the information it contains.)

Of course, what these proposals have in common is that they seem impossible—ludicrous, even. Surely, nothing like a Zeno machine could actually exist. Yet, if there is novel information originating in the world—whether at the Big Bang or in random quantum events—something equivalent to this must actually exist. In fact, while the Zeno machine allows you to create randomness, a source of randomness together with an ordinary computer allows you to do anything a Zeno machine can—thus, the two notions are equivalent.

The apparent impossibility simply stems from the fact that there is no possible theory of information generation; but to conclude from there that no mechanism thereof can be possible is both fallacious and flies in the face of the evidence we have to the contrary (namely, the existence of information in the world). But this is the strategy of the free will illusionists: every argument against its existence ultimately boils down to arguing that there is no possible mechanism for information creation—to running headfirst into the Münchhausen trilemma and considering its impossibility to be established thereby.

Truth Or Consequences

To flesh out the above, let’s have a look at the two most commonly cited—and arguably most convincing—arguments against free will. The first of these, put in its modern form by Peter van Inwagen in 1983, is the so-called Consequence Argument (CA). Put most simply, it goes: neither the facts of the past, nor the laws of physics, nor the outcomes of chance events (if any) are up to us; but together, these determine all the facts of the future. Therefore, the facts of the future likewise aren’t up to us. This is also the argument Hossenfelder appeals to: human beings, ultimately, are just humongous collections of particles either following deterministic laws or jumping around by chance. None of this is under our influence, hence, we have no hand in what we’re doing.

The argument commits the ‘Münchhausen fallacy’ in two separate ways. First, it simply posits chance events as a black box: no accounting is given of how a particle decides which road to take. It’s as if there’s a cosmic gambler rolling dice behind the scenes, whose outcomes then are imposed on the world. Randomness is conceived of as an external imperative dictating the motion of physical objects. As soon as one tries to go beyond that, however, the picture seems radically different: the Zeno machine isn’t a passive element in the creation of randomness, but quite to the contrary iterates its own state infinitely to produce random outputs.

Of course, intuition balks at admitting such a process to take place within, say, a single electron. But it has to be remembered that the Zeno process is only the closest approximation that can be formulated with the theoretical tools at our disposal: just because the map ends up looking complicated doesn’t mean the territory has to be.

The other sense in which the CA bumps up against Münchhausen is somewhat more subtle. The laws of physics are taken as a given, guiding the motion of particles with a stern hand. They are taken as part of the basic furniture of the universe; both their origin and their power to control are left unexplained. But if the laws could’ve been different, then what chose this particular set? Again we are sweeping the origin of information in the universe under the rug: nobody knows how something could come from nothing, but at least we can exile it out of consideration to the remote past. But like a bubble under freshly laid carpet, if you push it down here, it just pops up somewhere else.

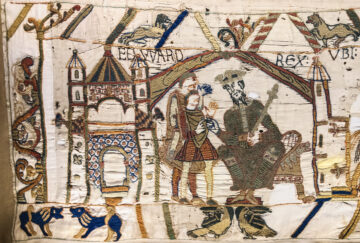

However, there’s an alternative conception on the market: Scottish philosopher David Hume famously formulated a position skeptical of causality, under which there is nothing but regularities in the patchwork of events making up the history of the universe. Any patterns in this patchwork then are what we call ‘laws of physics’, just as the pattern a weaver has embroidered into the carpet we’re still trying to flatten might be called a ‘law of design’. But the weaver was not controlled by this law—it’s his actions that bring it into existence. Moreover, just as the design is only fully appreciable once it’s completed, so too are the laws of physics fully specified only in the limit of the distant future—leaving the world in the here and now a little bit of wriggle.

Thus, neither chance events nor the laws of physics are necessarily not ‘up to us’: chance events may be points where the laws fail to fully specify the future, and we may be able to add to the design stitch by stitch.

There are thus significant reasons to doubt the conclusion of the CA. But typically, in my experience, when confronted with this, its proponents motte-and-bailey back to a different—and in my opinion, much stronger—argument. While it is often left somewhat implicit, the best full formulation of it I am aware of is due to Galen Strawson, who introduced it as the Basic Argument (BA) in a classic 1994 paper. It is deceptively simple: in order to be responsible for our actions, we ought to be responsible for the mental state causing these actions; but it is itself an action to ‘fix’ a particular mental state. Thus, we arrive at an infinite regress. (Note how this is prefigured in the quotation above that Einstein ascribes to Schopenhauer.)

The BA does not hinge on the contingent facts of the universe—laws of physics, chance events—to make its case. If it is sound, then free will is logically impossible as opposed to merely irreconcilable with the universe as we encounter it. But it is also explicit in committing the Münchhausen fallacy: it takes the infinite regress as sufficient to exclude the very possibility. The Zeno machine as introduced above could simply traverse the regress and come out the other side, as could something of equivalent capabilities. And again, if there is any means to create information, then something of equivalent capabilities to the Zeno machine must exist. To put it the other way around: if the BA were sound, then nothing could produce randomness, and there could not be any production of information at the beginning of the universe. Nor could there be laws of physics, as they, too, contain a nonzero amount of information. The fact that anything exists at all thus should be cause enough to doubt the argument.

Theoretical explanation works by deriving consequences from initial data—axioms, premises, stipulations. These data are only transformed in the process, and such transformations can’t increase the total amount of information. Thus, when we direct our theoretical gaze to those points where information is produced—the origin of the universe, chance events, or the free choices of individual agents—it necessarily flounders. It is then quite simply a mistake to take this epistemic hurdle to mean an ontological impossibility—that is, to believe that there is no territory where we can’t draw a map.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.