by Marie Snyder

The recent show Pluribus has got me thinking differently about the kind of ideal state that might be a laudable direction and how to get there. The show is overtly about a hive mind interconnection, that started with a lab-leaked experiment, which affects almost all of the world except for 13 people who have natural immunity. We follow the trajectory of one of these anomalies, Carol, who gives them their titular name, not for “many,” a direct translation, but as her own invention: “the plural of succubus.”

The recent show Pluribus has got me thinking differently about the kind of ideal state that might be a laudable direction and how to get there. The show is overtly about a hive mind interconnection, that started with a lab-leaked experiment, which affects almost all of the world except for 13 people who have natural immunity. We follow the trajectory of one of these anomalies, Carol, who gives them their titular name, not for “many,” a direct translation, but as her own invention: “the plural of succubus.”

There will be no significant spoilers here; this isn’t about the show specifically, but about its depiction of a perfectly efficient and seemingly happy and altruistic society. Is Carol the last one left in the cave, or is she the only one who’s on the outside?

The hive all works together effortlessly as one, with a prime directive to do no harm, as they distribute food worldwide with the utmost equity. They don’t step on bugs or swat flies. They will eat meat if it’s already dead, but they won’t kill it themselves. They also won’t pluck an apple from a tree. They don’t interfere with life. They can’t lie overtly. It’s all very pleasant. The hive won’t harm a living body; however, they didn’t mind obliterating the human spirit of 8 billion people without explicit consent, rendering their ethics questionable.

Connections to the show have been made with AI and Covid, so it may be useful to keep in mind that the show was originally written over ten years ago. If looking for authorial intent, those aren’t necessarily parallels. At that link, the lead of the show, Rhea Seehorn said she originally asked if it’s about addiction, and it’s not that either. There’s an element of just exploring human nature and what brings us happiness, and she likes journalists who “want to talk about philosophical questions about what this is bringing up for them. And we’re hearing all these different things. It’s wonderful.” I’m game! Read more »

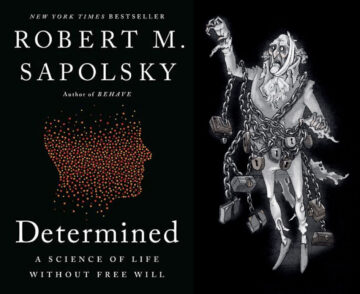

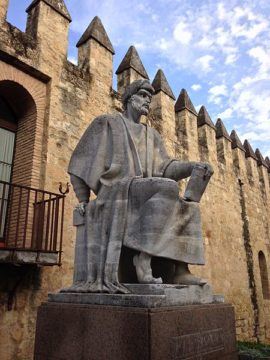

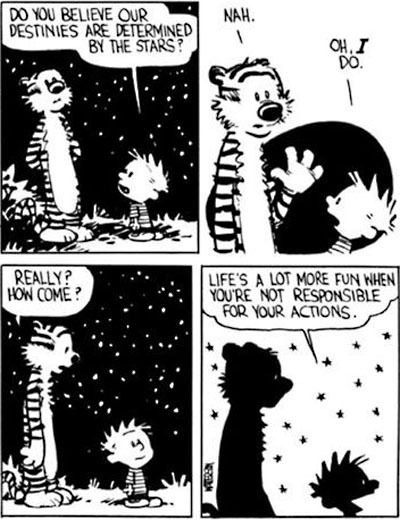

What can I make of these decisions emerging out of the blue, which I appear to act upon “freely?” What are the consequences of how I choose to react to them? Although these are vague philosophical musings, let’s look instead at the science of it all. I’m a layman, neither scientist nor philosopher, but as we are rediscovering, scientists are a less fuzzy lot than philosophers. I’m more likely to ask the woman with the medical degree about the true meaning of my dry cough than to ask philosopher

What can I make of these decisions emerging out of the blue, which I appear to act upon “freely?” What are the consequences of how I choose to react to them? Although these are vague philosophical musings, let’s look instead at the science of it all. I’m a layman, neither scientist nor philosopher, but as we are rediscovering, scientists are a less fuzzy lot than philosophers. I’m more likely to ask the woman with the medical degree about the true meaning of my dry cough than to ask philosopher