by Bonnie McCune

When my grandson was about two, I heard him stirring from his nap and went to his bedroom to get him up. He saw me at the door and clambered to his feet, clinging to the rail of his crib. “I got eye blooows,” he announced with pride, indicating with a pointed finger the yellow fuzz framing one eye.

I can imagine his curiosity as he first felt the ridge frequently called the brow ridge, the bony prominence above the eyes, known also as the supraorbital ridge. Touching the hairs and wondering what in the heck they are. Asking his parents why his face sprouted these strange growths. Checking faces of people around him for similar protrusions.

A momentous discovery, probably more for me than for him. It’s difficult for adults to get any view, even a squinty-eyed one, into the mind of a child just learning about himself and life. I was lucky. This particular child, at that precise time, paired verbal skills with a questioning mind and was able to say what he was thinking. I’d never caught a glimpse of the process before although I’d wondered how a kid learns.

I’ll give you an answer. It’s the same way a kid learns about a roly-poly bug and how it faces danger. They poke at it. Go nudge something and get excited about it, learn about it. This is actually how we continue to learn about life in all its fascinating variations. We witness some phenomenon, wonder about it, and learn and think.

We don’t claim we’re always right. Aging is a particularly delicate topic. Some of us don’t want to admit we’re not as charming or beautiful or strong or healthy as we once were. So we cover up with white lies and smiles.

But how does each of us determine, and ADMIT, we’re old? Read more »

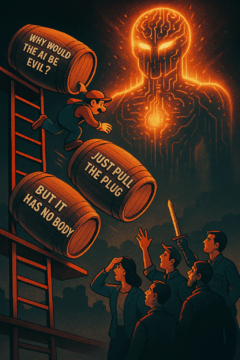

“A clearly written and compelling account of the existential risks that highly advanced AI could pose to humanity.” — Ben Bernanke

“A clearly written and compelling account of the existential risks that highly advanced AI could pose to humanity.” — Ben Bernanke

Natalie Bakopoulos: Thank you so much, Philip, for starting this conversation, and for these wonderful observations and connections. You’re absolutely right, I was indeed playing with the idea of “beginnings.” “Here in Greece,” the narrator says, “the rivers rarely have a single source: They spring from the mountains at several places.” I also wanted to think about the arbitrariness of origin and a way of thinking about belonging that wasn’t necessarily about “roots”—but instead rhizomes, as Edouard Glissant, and others, might say.

Natalie Bakopoulos: Thank you so much, Philip, for starting this conversation, and for these wonderful observations and connections. You’re absolutely right, I was indeed playing with the idea of “beginnings.” “Here in Greece,” the narrator says, “the rivers rarely have a single source: They spring from the mountains at several places.” I also wanted to think about the arbitrariness of origin and a way of thinking about belonging that wasn’t necessarily about “roots”—but instead rhizomes, as Edouard Glissant, and others, might say.

The wealthy and powerful have always used the narrative to their advantage. The narrative defines them as superior in some way, and thus deserving of their power and wealth. In ancient times, they might be descended from the Gods, or at least favored by them or otherwise connected to them, perhaps through special communicative powers that granted them insights into the will of the Gods or God. In modern capitalist societies, that narrative promotes a fantasy of merit. You are rich and/or powerful because you are better. You are more civilized, better educated, more intelligent, or blessed with an exceptional work ethic. These narratives cast wealth and/or power as not only justifiable, but deserved.

The wealthy and powerful have always used the narrative to their advantage. The narrative defines them as superior in some way, and thus deserving of their power and wealth. In ancient times, they might be descended from the Gods, or at least favored by them or otherwise connected to them, perhaps through special communicative powers that granted them insights into the will of the Gods or God. In modern capitalist societies, that narrative promotes a fantasy of merit. You are rich and/or powerful because you are better. You are more civilized, better educated, more intelligent, or blessed with an exceptional work ethic. These narratives cast wealth and/or power as not only justifiable, but deserved.

In

In

In a recent essay,

In a recent essay,

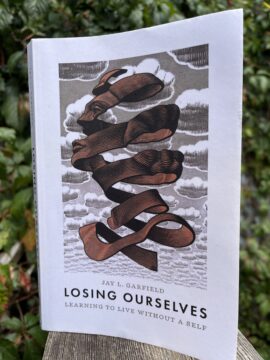

We’re living at a time when the glorification of independence and individualism is harming the world and others in it, as well as leading to an epidemic of loneliness. According to Jay Garfield, the root of suffering is in our self-alienation, and one symptom of our alienation is clinging to the notion that we are selves. “We are wired to misunderstand our own mode of existence,” he writes in his brief yet substantial 2022 book,

We’re living at a time when the glorification of independence and individualism is harming the world and others in it, as well as leading to an epidemic of loneliness. According to Jay Garfield, the root of suffering is in our self-alienation, and one symptom of our alienation is clinging to the notion that we are selves. “We are wired to misunderstand our own mode of existence,” he writes in his brief yet substantial 2022 book,