by Herbert Harris

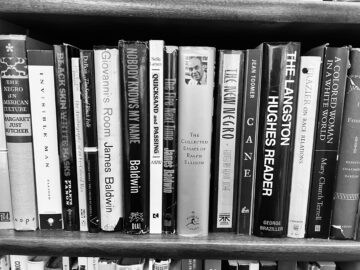

The greatest privilege of my childhood was growing up in a house where books had their own room.

My father’s library occupied the second floor, the only room without a window air-conditioning unit. On summer afternoons in Washington, DC, when the heat and humidity pressed down like a weight, the rest of the house hummed and rattled with machines straining to keep up. The air in the library stayed stubbornly still. It was the early 1970s, and I was on summer break after tenth grade, retreating there to find the peculiar solitude this room alone offered. Each book I opened sent up a cloud of dust that glittered in the angled sunlight. Shutting the door turned the room into a sauna, but in that quiet stillness, I didn’t mind. It felt like the price of admission to a different world.

The previous summer had unfolded differently. I had just finished ninth grade, where we surveyed the classics of English literature and retraced the decisive moments of Western civilization, reliving the deeds of its great men and women. I spent long afternoons in the library, sinking into those books as the heat pooled around me. I melted into a reclining chair and wandered through the past. That immersion had felt complete, even sufficient. But this summer, I arrived with a different appetite. I was growing skeptical of the Eurocentric narratives threaded through everything I was learning. I sensed there were other stories and vantage points, and I came looking for them.

I picked up the book I had been reading a few days earlier and turned to the page marked with an index card. I searched for the sentence I remembered, but at first the words slipped past me. James Baldwin was writing about a Swiss village, about children shouting “Neger” as he walked through the snow. Seeing the word on the page registered instantly, not as surprise but as recognition. I had learned early what it meant to be called that name in its American form. That knowledge had settled into my body long before I could articulate it. Read more »

If you had to design the perfect neighbor to the United States, it would be hard to do better than Canada. Canadians speak the same language, subscribe to the ideals of democracy and human rights, have been good trading partners, and almost always support us on the international stage. Watching our foolish president try to destroy that relationship has been embarrassing and maddening. In case you’ve entirely tuned out the news—and I wouldn’t blame you if you have—Trump has threatened to make Canada the 51st state and took to calling Prime Minister Trudeau, Governor Trudeau.

If you had to design the perfect neighbor to the United States, it would be hard to do better than Canada. Canadians speak the same language, subscribe to the ideals of democracy and human rights, have been good trading partners, and almost always support us on the international stage. Watching our foolish president try to destroy that relationship has been embarrassing and maddening. In case you’ve entirely tuned out the news—and I wouldn’t blame you if you have—Trump has threatened to make Canada the 51st state and took to calling Prime Minister Trudeau, Governor Trudeau.

In daily life we get along okay without what we call thinking. Indeed, most of the time we do our daily round without anything coming to our conscious mind – muscle memory and routines get us through the morning rituals of washing and making coffee. And when we do need to bring something to mind, to think about it, it’s often not felt to cause a lot of friction: where did I put my glasses? When does the train leave? and so on.

In daily life we get along okay without what we call thinking. Indeed, most of the time we do our daily round without anything coming to our conscious mind – muscle memory and routines get us through the morning rituals of washing and making coffee. And when we do need to bring something to mind, to think about it, it’s often not felt to cause a lot of friction: where did I put my glasses? When does the train leave? and so on.

Once again the world faces death and destruction, and once again it asks questions. The horrific assaults by Hamas on October 7 last year and the widespread bombing by the Israeli government in Gaza raise old questions of morality, law, history and national identity. We have been here before, and if history is any sad reminder, we will undoubtedly be here again. That is all the more reason to grapple with these questions.

Once again the world faces death and destruction, and once again it asks questions. The horrific assaults by Hamas on October 7 last year and the widespread bombing by the Israeli government in Gaza raise old questions of morality, law, history and national identity. We have been here before, and if history is any sad reminder, we will undoubtedly be here again. That is all the more reason to grapple with these questions.