by Barbara Fischkin

I arrived in Ireland in the mid-1980s to cover the seemingly intractable bloody conflict colloquially known as “The Troubles.” I studied up on materiel: Armalite rifles, homemade fertilizer bombs, the plastic bullets protestors ducked. And on the glossary of local politics: Loyalists were mostly Protestants who wanted to remain British citizens; Republicans were mostly Catholics who yearned for a united Irish nation. I interviewed people on both sides of the conflict but more women than men. I wanted to make their voices heard in the United States.

I was taken by one issue that had already created international headlines—the strip searches of female political prisoners.

But the stories I read did not quote the women who were being strip searched. They quoted politicians and sociologists instead of the women themselves. The stories said the policy was routine, part of the process of getting inmates out of civilian clothes and into prisoner uniforms. Not true. This was actually a well-conceived British military psychological operation to humiliate the women, a technique intended to “break” the women.

I decided that the only way to write about this was to getting inside the 100-year-old stone walls of Her Majesty’s Prison Armagh—and to talk to the women directly.

But to get in, even to speak to only one woman, I had to lie. I could not say I was a reporter. I had to say I was a cousin, visiting from the states. The Northern Ireland Office, run by dutiful Protestant colonists controlled by the British, kept the press out. Perpetrators of abuse do not like publicity. Now, as St. Patrick’s Day approaches, and two larger wars rage—wars that unlike the one in Ireland threaten us all—my mind keeps racing back to what is better known as “Armagh Jail.”

Yes, this is a small story about a small sectarian war. But when it comes to getting the truth out, wars are often all the same. Like Ireland, the superiority of one culture over another is at the core of the killing.

There were never more than forty women political prisoners at Armagh Jail, all of them Catholic, some convicted, some awaiting trial. Most had been victims of this war against Catholics and the accompanying discrimination in regard to employment, language and security since childhood. And yes, there were some murderers and some who had committed lesser offenses. Others were arrested simply because they were Catholic at the wrong place at the wrong time. In this way, as well, the centuries-old war in Ireland resonates today.

It was my husband who brought me to Belfast. Irish Americans felt the troubles were not being covered in the American press and to remedy this, St. John’s University in Queens, New York, had given him a grant to write from Northern Ireland for Newsday, where we had both been on staff. I took the year off to freelance for Newsday and other publications—and it was Newsday that wanted the Armagh story.

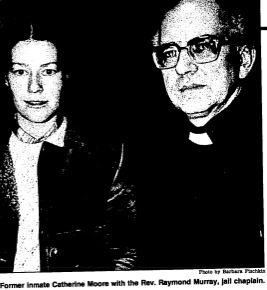

I called the Northern Ireland Office from Dublin, where I was writing about the Republic’s own feminist lapses, to ask if I could speak to women in the prison. A spokesman named Jim Hamilton told me: “We rarely let reporters in” adding that I was not going to be an exception to the rule. Undeterred, I took a train north to Belfast, where my husband through his own connections, introduced me to the Armagh Jail chaplain, Father Raymond Murray. Father Murray, later an honored monsignor, was already a hero of the revolution. He had many nationalist irons in the fire. In a quiet way, he seemed fearless. And so, a plan was hatched.

I told the guards at Armagh Jail that I was the American cousin of one of their prisoners, Siobhan O’Hanlon. (Father Murray had alerted her that I would be coming—and that she would be quoted.) I used my married name, Mulvaney. Not my byline which was then, as now, Fischkin. As for the guards, they also looked war-weary and they waved me right in. I suspected they knew the real reason why I was there and did not care or, perhaps, personally and privately objected to the policy

Siobhan O’Hanlon was then 23. She had known war since she was seven. She was serving seven years and awaiting a second trial, both for crimes related to being near the vicinity of bombs and explosives. That was all they had on her—no evidence only proximity. She had not confessed. She was not repentant. And she was strip searched. The guards who conducted this search were all women. Siobhan told me that did not make it any easier. She told me that being strip searched meant she had to stand naked in front of someone whose family had been enemies of her family for centuries. She told me that Northern Irish women like her were modest Catholics—this was true—who would not undress even in front of their own sisters. She told me about other women, for whom the strip searches were much harder. They had to undress while menstruating or while still bloody after difficult births.

I had no notebook or recorder with me. That would have given it all away. Instead I tried to memorize everything this young woman told me. I left the prison, ran into the women’s “loo,” at a nearby café and wrote it all down on toilet paper.

As I recently re-read this story I wrote in 1985, I realized that the sexual fears of the Armagh women prisoners would take on new meaning today, with our deeper understanding of gender identity and fluidity.

After the story was published—with a nice full-page feature section display—I picked up the phone in the Dublin flat, where we spent time when not living in Belfast. “How did you do it?” Jim Hamilton, the spokesman asked. “I can’t tell you,” I said. He chuckled. He did not sound angry. Dismissive was more like it. As if the status quo would remain the same and people would forget that women were ever strip-searched in Northern Ireland. They have not forgotten.

And, as has been learned with even more intensity since September 11, torture is not useful unless it extracts true information, which it rarely does. Or stops a crime. When I asked Spokesman Hamilton what was found during the strip searches, he replied that the searches “are very much a deterrent. We have no detection equipment that can do this one hundred percent at the moment.” I asked him what was found. He said that in more than two years only four items of contraband had been detected: An unspecified sum of money, an uncensored letter, a bottle of prescription drugs and a bottle of 47 tranquilizers. Huh? I thought. I asked the prison’s best known alum—Bernadette Devlin McAliskey, perhaps the most famous of Irish Republican women, what she thought “They’ve tried. almost every form of punishment and now they’ve gone to basic degradation,” she said.

In these times, it is crucial to note that in the 19th century, the British punished the Irish with a “hunger,” which is the correct term for a man-made shortage of food. During the misnamed “famine,” after the failure of the island’s potato crop, the British government exported 26 million bushels of grain and countless thousands head of beef cattle and veal calves. They also banned the Irish language.

In the 20th century, the Soviets created a hunger to starve Ukrainians, stoic people whose culture and language Putin is still trying to eradicate with his brutal war. What has happened in Gaza, is a hunger not a famine. It is a hunger created by Netanyahu, whose own loyalists are now trying to come up with excuses to explain the latest massacre of civilians. As an opinion piece in Jewish Forward noted, the people of Gaza never should have been starved in the first place.

Maybe we are doomed to be a civilization at war.

Yet there is hope. And it comes, from Ireland, the site of that centuries-long war, with a peace plan that has been in the works for a mere 26 years, starting with the Good Friday agreement. There has been compromise with tolerable concessions. Brexit helped bring peace, too, in that it threatened the pocketbooks of people North and South.

Last Friday, at this year’s annual Irish Unity Summit in New York City, it was suggested that there might be a united Ireland by 2030. I have lost track of Siobhan O’Hanlon. But I hope she is alive to hear this.

***

Note: For readers who would like to see a copy of the original Newsday story I wrote about Armagh Jail, it can be found on ProQuest or in some library newspaper archives, including “Newsday Historical.” Headline: “Touching an Irish Nerve. At Armagh Jail, strip searches of women prisoners have sparked protests, Fischkin, Barbara Newsday (1940-); Jul 16, 1985; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Newsday pg. A3