by Chris Horner

What does it mean to live a Good Life in the secular west? Good can mean more than one thing, of course: apart from moral good – doing the right or ‘good’ thing, there is the idea of ‘good’ as flourishing, being happy, fulfilled. The latter matters to us a lot, judging by all the self-help books, YouTube influencers, Rules for Life and so on. For very many lucky enough not to have to worry about poverty or war there still seems a grinding anxiety about how to achieve a happy life. That life seems to be Elsewhere. But why? Some would argue that the angst is due a loss of a shared way of life, one grounded in a conception of human purpose. So, we get nihilism and sense of anomie. Yet lost wallets are returned, and courtesy is still exhibited in everyday situations. If this is moral anarchy, it is not as chaotic as one might expect. Nevertheless. I think something has changed for moderns.

With the decline of an Authority often associated with the Christian church in the West, many people experience the question of what one should do as a burden. As an unlamented Paternal Authority wanes, anxiety about happiness and fulfilment takes its place. The new Superego command is to enjoy oneself, be the best one can be, stay fit, be loved, and be attractive. Consequently, we turn to an army of experts and coaches eager to provide us with ‘rules for living’. And the appetite for moral judgment hasn’t left us either: yet more rules about what one ought to say or not say (rather than action that might change anything).

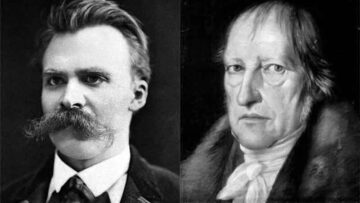

Modernity—however we define it—follows the Enlightenment. Kant described Enlightenment as the end of tutelage and the accession to maturity, with the responsibilities that come with freedom. Freedom is understood as the end of the tyranny of princes and prelates, the chance to fulfil one’s desires. However, greater knowledge of the self leads to greater doubts about those desires, and the causes of Desire itself. The autonomy promised by Enlightenment seems compromised from the start. While Nietzsche, along with Freud, is regularly cited as the key figure in this creeping sense that the subject isn’t master in their own house, Hegel foreshadows both. For Hegel, too, there are no simple, undivided identities: we are divided subjects. Read more »

If you had to design the perfect neighbor to the United States, it would be hard to do better than Canada. Canadians speak the same language, subscribe to the ideals of democracy and human rights, have been good trading partners, and almost always support us on the international stage. Watching our foolish president try to destroy that relationship has been embarrassing and maddening. In case you’ve entirely tuned out the news—and I wouldn’t blame you if you have—Trump has threatened to make Canada the 51st state and took to calling Prime Minister Trudeau, Governor Trudeau.

If you had to design the perfect neighbor to the United States, it would be hard to do better than Canada. Canadians speak the same language, subscribe to the ideals of democracy and human rights, have been good trading partners, and almost always support us on the international stage. Watching our foolish president try to destroy that relationship has been embarrassing and maddening. In case you’ve entirely tuned out the news—and I wouldn’t blame you if you have—Trump has threatened to make Canada the 51st state and took to calling Prime Minister Trudeau, Governor Trudeau.

It doesn’t take a lot of effort to be a bootlicker. Find a boss or someone with the personality of a petty tyrant, sidle up to them, subjugate yourself, and find something flattering to say. Tell them they’re handsome or pretty, strong or smart, and make sweet noises when they trot out their ideas. Literature and history are riddled with bootlickers: Thomas Cromwell, the advisor to Henry VIII, Polonius in Hamlet, Mr. Collins in Pride and Predjudice, and of course Uriah Heep in David Copperfield.

It doesn’t take a lot of effort to be a bootlicker. Find a boss or someone with the personality of a petty tyrant, sidle up to them, subjugate yourself, and find something flattering to say. Tell them they’re handsome or pretty, strong or smart, and make sweet noises when they trot out their ideas. Literature and history are riddled with bootlickers: Thomas Cromwell, the advisor to Henry VIII, Polonius in Hamlet, Mr. Collins in Pride and Predjudice, and of course Uriah Heep in David Copperfield. There is something repulsive about lickspittles, especially when all the licking is being done for political purposes. It’s repulsive when we see it in others and it’s repulsive when we see it in ourselves It has to do with the lack of sincerity and the self-abasement required to really butter someone up. In the animal world, it’s rolling onto your back and exposing the vulnerable stomach and throat—saying I am not a threat.

There is something repulsive about lickspittles, especially when all the licking is being done for political purposes. It’s repulsive when we see it in others and it’s repulsive when we see it in ourselves It has to do with the lack of sincerity and the self-abasement required to really butter someone up. In the animal world, it’s rolling onto your back and exposing the vulnerable stomach and throat—saying I am not a threat.

In the game of chess, some of the greats will concede their most valuable pieces for a superior position on the board. In a 1994 game against the grandmaster Vladimir Kramnik, Gary Kasparov sacrificed his queen early in the game with a move that made no sense to a middling chess player like me. But a few moves later Kasparov won control of the center board and marched his pieces into an unstoppable array. Despite some desperate work to evade Kasparov’s scheme, Kramnik’s king was isolated and then trapped into checkmate by a rook and a knight.

In the game of chess, some of the greats will concede their most valuable pieces for a superior position on the board. In a 1994 game against the grandmaster Vladimir Kramnik, Gary Kasparov sacrificed his queen early in the game with a move that made no sense to a middling chess player like me. But a few moves later Kasparov won control of the center board and marched his pieces into an unstoppable array. Despite some desperate work to evade Kasparov’s scheme, Kramnik’s king was isolated and then trapped into checkmate by a rook and a knight.

A Republican used to be someone like Dwight Eisenhower, a moderate who worked well with the opposing party, even meeting weekly with their leadership in the Senate and House. Eisenhower expanded social security benefits and, against the more right-wing elements of his party, appointed Earl Warren to be the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. Warren, you’ll remember, wrote the majority opinion of Brown v Board of Education, Miranda v Arizona, and Loving v Virginia. If Dwight Eisenhower were alive today, he would be branded a RINO and a communist by his own party. I suspect he would become registered as unaffiliated.

A Republican used to be someone like Dwight Eisenhower, a moderate who worked well with the opposing party, even meeting weekly with their leadership in the Senate and House. Eisenhower expanded social security benefits and, against the more right-wing elements of his party, appointed Earl Warren to be the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. Warren, you’ll remember, wrote the majority opinion of Brown v Board of Education, Miranda v Arizona, and Loving v Virginia. If Dwight Eisenhower were alive today, he would be branded a RINO and a communist by his own party. I suspect he would become registered as unaffiliated.  If philosophy is not only an academic, theoretical discipline but a way of life, as many Ancient Greek and Roman philosophers thought, one way of evaluating a philosophy is in terms of the kind of life it entails.

If philosophy is not only an academic, theoretical discipline but a way of life, as many Ancient Greek and Roman philosophers thought, one way of evaluating a philosophy is in terms of the kind of life it entails.