by Thomas O’Dwyer

We still recall the 1920s as the Roaring Twenties or the Jazz Age. Not many will know that the decade which began 200 years ago with U.S. President James Monroe in office was the Era of Good Feelings, a name coined by a Boston newspaper. In 1820, a presidential election year, Monroe ran for his second term — he was unopposed, so there was really no campaign. He won all the electoral college votes except one, narrowly leaving George Washington to remain as the only president ever to score a unanimous victory.

In the flood of commentary, prophecy, gloom, and nostalgia that has greeted the start of a new decade, many of the comparisons with the past have fixed on the 1920s. That age is almost within living memory, maybe not personal, but at least familial, through the reminiscences and records of parents or grandparents. And for the first time in human history, we have extensive evidence in sound, film, and photography from the fascinating 1920s.

But is also interesting to look even further back, another 100 years, to the 1820s. For here, most people can agree, lie the true roots of the science-driven modernity that was more spectacularly obvious in the 1920s and beyond. Full documentary records in the 1820s were sparse but growing. Nicephore Niepce developed the first photograph in 1826 but sound reproduction would have to wait another 50 years for Thomas Edison. The first moving-picture sequence was made by Frenchman Louis le Prince in 1888. The new inventions and discoveries of the 1820s were physically primitive, but loaded with hidden significance and promise that no one could have guessed.

The decade was dominated by the Industrial Revolution, thrusting first Britain, then the entire West, into an explosion of development. Beginning unobtrusively with technical improvements in the dreary textile mills of northern England, technology began to advance significantly as armies of coal miners fed the giant engines to power the factories and expanding cities. Textiles, rail transport and engineering projects surged and grew more prominent across the decade. At the same time, colonialism gained ground in Africa and Asia, and in China, the Qing Dynasty began to open up to foreign traders, particularly from Europe. In 1825 the world’s first modern railway, the Stockton and Darlington Railway, opened in England.

On the dark and evil side, slavery and child labour fed the greedy new capitalist monster. American skeptics of the day suggested that “Era of Good Feelings” should be pronounced with a sarcastic sneer. Despite Monroe’s sweeping and unopposed victory, the American political atmosphere was riddled with strains and divisions within the government and the Democratic-Republican Party. (Monroe’s election was the last clean sweep of the dominant Democratic-Republican Party which vanquished the vanishing Federalists before itself disintegrating in 1824. One faction of the defunct party eventually became the Democratic Party led by Andrew Jackson).

Of course, America is not the world and the start of the 19th century was the beginning of what we call modernity across the planet. In 1802 the world’s population reached 1 billion for the first time – North America was home to a mere 7 million of those, while Latin America already had 24 million. In South America, wars of independence erupted and raged on until Brazil, Bolivia, Peru, and Uruguay won self-determination. In their struggles, the Latin states were powerfully bolstered by the American Monroe Doctrine. This was issued in 1823 and stated that any attempt by a European power to take control of an independent state in North or South America would be regarded as “the manifestation of an unfriendly disposition toward the United States.” This was a significant blow against European colonialism, though not a decisive one, as the rise of the global British Empire was really only beginning.

The early years of the century were dominated by the wars of Napoleon Bonaparte in Europe. France’s empire rose swiftly before falling just as quickly after Napoleon’s attempts to conquer Russia, the War of 1812 (a Napoleonic spillover into America), and Napoleon’s ultimate defeat in 1815 by the British, Dutch and Germans at Waterloo. The tentacles of British and Dutch imperialism began to reach out to Africa and Asia through trade policies dominated by powerful corporations like the East India Company which virtually conquered India. In 1824 the name Australia was adopted as the official name of the country first known as New Holland.

With our 2020 hindsight, we can now discern in the decade of the 1820s the first tiny footprints that have evolved into the giant boot of progress stamping on the face of the planet. Thoughts of progress did not dominate American minds as 1820 rolled in. Just behind them was the great Panic of 1819. Peace may have come after Napoleon’s wars, but prosperity did not. The so-called panic was the first huge financial crisis to hit the United States in a time of peace and it brought about a general collapse of the economy that only began to turn around after two years. France and Britain had been at war on and off since the 17th century, and while they warred, the young United States had prospered. American goods were in high demand to help the Europeans sustain themselves during the conflicts. Once the wars ended, U.S.-made products were no longer in such demand and Americans had to evolve from a colonial-based trading status with Europe and become an independent economy. The severity of the global market adjustments was made worse by an American banking crisis caused by runaway speculation in public lands.

When we are in upheavals, we can only see the bad, not the new horizons they may uncover. Today economic historians say that the Panic of 1819 was actually the transition of the United States into the modern business cycle. “All beginnings are obscure, whether owing to their minuteness or their apparent insignificance,” wrote the 19th-century classical historian, Theodor Gomperz. “When they do not escape reception they are liable to include observation. The sources of history, too, can only be tracked at a footpace.”

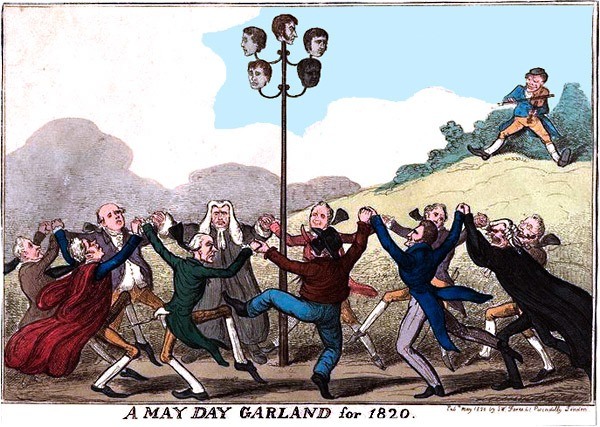

As well as its opaque foreshadowings, the 1820s era cast some farewell glances to the past, drawing lines under attitudes and practices deemed medieval and barbaric. In 1820 the last criminals to be hanged, drawn, and quartered were executed in London. The five men subjected to this public savagery were members of the Cato Street Conspiracy — a plot to murder the prime minister and all his cabinet ministers. When the convicted men were beheaded after hanging, the watching crowd became angry and the executioners had to be locked in the nearby prison for their safety. But it took another 50 years before the punishment was finally removed from the statute books. Amid such signs of departing dark ages, there were promising reminders or markers of culture and better times ahead.

In April 1820, a Greek peasant on the island of Milos found the stunning marble statue of Venus de Milo in a niche under some ruins. It was dated at around 130 BCE, a reminder that the distant past once held beauty as well as barbarism. In March, the Royal Astronomical Society was founded in London, mostly through the efforts of one Charles Babbage. Its original aim was to standardise astronomical calculations and to propagate the data collected as widely as possible. These ideas were linked to Babbage’s theories on computation. In 1822 he published proposals for a mechanical computer, and in 1824 he won the Royal Society’s gold medal “for his invention of an engine for calculating mathematical and astronomical tables.”

All the basic ideas of modern computers were in Babbage’s analytical engine, although he never built a working model. Having invented the first mechanical computer that eventually led to our complex electronic designs, Babbage is generally regarded as the “father of the computer age.” In 1828, a priest and member of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Ányos Jedlik, unveiled the world’s first dynamo and electric motor. From this distance, we can now see that by the end of the 1820s, essential technical elements were already in place or under development for the great leap forward in human achievement that would mark the 20th century.

In 1827 a Romanian, Petrache Poenaru gained a French patent for the invention of the first fountain pen with a replaceable ink cartridge. But two years later, in America William Burt obtained the first patent for a different writing instrument that was going to take the world a lot farther than any pen — the first typewriter. Consider how far the humble keyboard has come in 200 years in its marriage to Babbage’s electronic descendants. But another patent was granted in 1829, one many of us would like to go back in time and strangle at birth. It was for the accordion.

In the first year of the new decade, several newborns slipped into a world they were destined to change. In January Anne Brontë was born, the youngest of England’s most famous literary sisterhood. In America William Sherman, the future Civil War general, arrived in February, as did Susan B. Anthony, the campaigner for women’s rights and suffrage. In Italy, the man who would unite the country for the first time since the sixth century, Victor Immanuel II, was born. And in England, along came the founder of modern nursing and healthcare, Florence Nightingale.

The most significant death in that year was probably King George III, “the mad king who lost America,” but also the man who defeated Napoleon. He also created the United Kingdom of Britain and Ireland, a tie that bound somewhat more tightly than the American one and which would take the Irish another hundred years to sever. George had lived for 82 years and reigned for 59 of them. His life and his reign were longer than of any of his predecessors and subsequent kings. Only two monarchs, both women, Victoria and Elizabeth II, have since lived and reigned longer. His death definitively marked the passing of an era in the same way as Victoria’s would in 1901.

Many of the political or international events that dominated newspaper headlines during 1820s are long forgotten, a reminder that today’s huge political crisis might not even make it as a footnote in a history book. A European dispute that bumbled on for decades and into the following century was the notorious Schleswig-Holstein Question. It was a mere territorial dispute about two provinces on the border between Germany and Denmark. They were claimed by both countries but the residents of the provinces demanded a say in the outcome. However, the residents were also divided about which country they wished to join. The issue and its negotiations became so convoluted that British Prime Minister Lord Palmerston famously commented: “The Schleswig-Holstein question is so complicated, only three men in Europe have ever understood it. One was Prince Albert, who is dead. The second was a German professor who became mad. I am the third and I have forgotten all about it.” And so has everyone else on the planet.

Without doubt the evolving history of the modern world over the past 200 years belongs to the scientific and technological seeds that began to sprout in the 1820s, allied to the new economic practices and institutions that made their development possible. When we look at the arts and culture however, the picture becomes more diffuse, the threads linking those days to us more broken. The Scottish novelist Sir Walter Scott attained international literary celebrity during his lifetime as a bestselling author. He features prominently on a list of the best books of the 1820s compiled by the booklovers’ website Goodreads. Yet who today still reads Ivanhoe, Waverley, The Heart of Midlothian or The Bride of Lammermoor? On that same list, we find Washington Irving’s Legend of Sleepy Hollow and The Last of the Mohicans by James Fenimore Cooper as well as works by Honore de Balzac, Victor Hugo, and Thomas de Quincy. But the most surprising feature of the list which we are unlikely to see on such a compilation today is the amount of poetry — several volumes by Lord Byron, Percy Bysshe Shelly, Edgar Allan Poe, John Keats, Alexander Pushkin, Heinrich Heine, and other lesser-known poets.

Turning to music, we seem to be on more familiar ground in the 1820s, although none of the popular or music hall songs of those days have survived the journey. But this was the decade when the career of Ludwig van Beethoven really soared. To this day Beethoven remains one of the world’s most influential musicians, and his compositions are among the most performed by orchestras around the world. He has leaped over the centuries as Shakespeare has done in literature. The Ninth Symphony was premiered in Vienna in 1824 and has not been out of the classical repertoire since. It is part of UNESCO’s Memory of the World Programme and the choral movement is the national anthem of the European Union. In 1823 an eleven-year-old Franz Liszt performed a public concert, after which he was personally congratulated by Beethoven. In 1826, Beethoven completed his String Quartet, Opus 131. At the end of the decade, Felix Mendelssohn made his first visit to Britain. After conducting the first London performance of his concert overture to A Midsummer Night’s Dream, he took a trip to Scotland and discovered Fingal’s Cave in the Hebrides islands. The strange echoes in the cave inspired Mendelssohn’s Hebrides Overture.

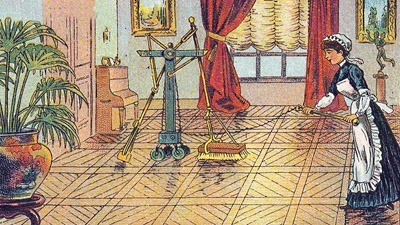

The tenuous links to our distant past, the start of things they could not then imagine were coming, and the dizzying progress for both good and ill, make it difficult to be anything but pessimistic about where humanity is headed. Perhaps that is because it makes one’s head ache to try to imagine what the world will look like in another 200 years. All one can safely predict is that all predictions will be wrong, most of them ludicrously so. Our images of the future may look as daft to people then as those of the 19th century look to us.

A cursory search of the few predictions made for our world 200 years ago revealed only one plausible prophet — a French illustrator who foresaw the Roomba. Well, it is a 19th-century Roomba, but the elements of the idea are there in the “electric scrubber”. The only anomaly is that my Roomba didn’t come with a French maid to shepherd it.