by Mark R. DeLong

In October 1938, 23-year-old Arthur Rothstein drove the roads on assignment to document the lives of the nation as part of his job in the Farm Security Administration (FSA). This time, his assignment was New Jersey, and in Monmouth County he was interested in where potato-picking migrants slept, usually in shacks near the fields they worked. He took lots of pictures of ramshackle buildings—ones you would easily assess as barely habitable: a leaning frame taped together with tar paper, a “silo shed” that sheltered fourteen migrant workers, a “barracks” with hinged wooden flaps to cover windows—in fact merely unscreened openings, one dangling laundry to dry. Rothstein, like his colleagues at the FSA during Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, documented the need for the government programs. Squalid housing matched the dirt and brutal labor of migrants, many of them cast into their situations by the disaster of the Great Depression.

Amidst such architectural photographs, one sticks out. Actually it is one of a pair of photographs, both taken indoors of sleeping quarters—no one would comfortably call them “bedrooms.” One shows a narrow unmade bed near a window shabbily curtained with a frayed and loosely hung blanket. In the other one, more tightly framed, the image draws close enough to reveal a carved headboard, a rumpled newspaper open to a full-page ad for Coca-Cola (“Take the high road to refreshment“) and other papers pushed to the corner of the bed. Neatly cut pictures of luxury cars from newspaper advertisements decorate the flimsy particle board wall that served as meagre insulation.[1]

When I saw the picture with the cars, I noticed a change in visual tone. The image felt hopeful.

An image of romance, glamour, and promise

In part, the photograph stands out because of telling details, which was a lesson Rothstein learned from the FSA. Rothstein was Roy Stryker‘s first hire for what was then called the “Historical Section” of the Resettlement Administration, which later became the FSA. Stryker hired Rothstein fresh out of Columbia University, where Rothstein had been preparing for medical school which, given the precarity of the Depression, he decided against attending. Stryker had a missionary zeal for the project of documenting American life in the tough times and urged his small cadre of photographers in the to capture small details, following not only his artistic and journalistic sense but probably also the practice of three of the accomplished photographer-artists in his group: Ben Shahn, Dorothea Lange, and Walker Evans. Rothstein recalled that Stryker emphasized “that it was important, say, to photograph the corner of a cabin showing an old shoe and a bag of flour; or it was important to get a close-up of a man’s face; and it was important to show a window stuffed with rags.”

In contrast to Rothstein’s bleak depictions of migrant barracks, this unmade bed with its tossed newspapers invoked hope. Details make the photo with the glued cars that flowed from the headboard. A line of cars ascend, towing our attention higher. Below them, Plymouths, Buicks, Packards, Dodges, trucks, delivery vans circle back or dive down into the wall’s triangularly spreading traffic. The collage swirls with activity. Some of the cutouts include smiling men and women. And in their midst, a team of horses plods toward the center of the room.

“The bed is empty, but we can imagine the car lover lying there after a hard day in the fields, projecting himself into the pictures and dreaming of escape and transformation,” wrote Virginia Postrel in The Power of Glamour (2013) when she considered the image. “The grilles of large vehicles point outward and, at the top of the display, a line of smaller cars drives up the wall toward the ceiling, the edge of the photograph, and, the sense of motion implies, a better future.”

Glamour and a rich modernity operate in the image, for the car at the time formed a nearly complete symbol of modernity and luxury. Certainly glamour keeps consumer urges moving, but, probably to post-modernist critics’ surprise, processes of glamour and fashion can also spur change and even revolutionary upheaval, the reordering and transformation of what people in a society can expect and hope. In the end, glamour may not only be a societal sedative or simply a tool of Madison Avenue agencies. It also prods—often in ways that are only partially steered.

The picture also invokes an archetype, which Rothstein may or may not have seen when he composed the shot. Postrel seems to have sensed it, since she poses the exhausted migrant worker to look at the cars climbing the wall, “projecting himself” and “dreaming” of his own transformation. Recall, for a moment, the story of Jacob’s Ladder (Genesis 28:10-15). Fleeing from his brother Esau’s wrath, Jacob traveled from Beer-sheba toward Haran, stopped for the night, and lay down, resting his head on a rock. “And he dreamed, and behold a ladder set up on the earth, and the top of it reached to heaven: and behold angels of God ascending and descending on it.” Jacob’s ladder serves as a roadway to and from heaven, delivering God’s promise to Jacob: “In thee and in thy seed shall all the families of the earth be blessed,” God tells Jacob in the dream. “And, behold, I am with thee, and will keep thee in all places whither thou goest, and will bring thee again into this land, for I will not leave thee.”

I look at the progression of automobiles ascending and descending where the migrant’s head would lay, and I think of how that biblical promise would resonate with a migrant worker—as if angels could drive cars in an American story that a tired laborer would dream.

A rolling picture frame for the American family

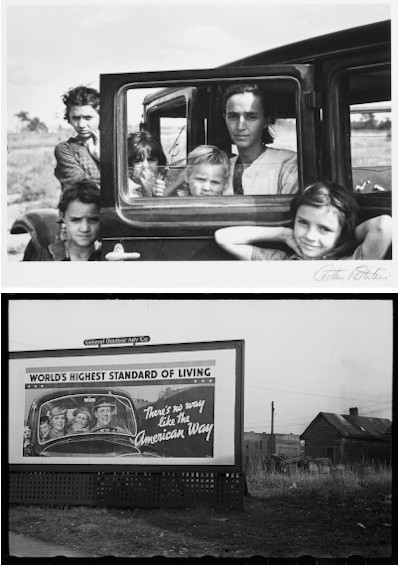

One of the most photographed of the billboards showed a white family of four and a dog. Mom, Dad, and the kids are framed within the car’s windshield as they motor beneath a banner proclaiming “WORLD’S HIGHEST STANDARD OF LIVING” and the campaign’s tagline, “There’s no way like the American Way.” The car encloses an Ideal American Family, with the effect of insinuating the automobile into the definitions of the family and the American Way. Rothstein incorporated the billboard in a photograph taken in Alabama in 1937; he devoted nearly a half of the frame to the billboard’s desolate surroundings. In it, the happy family smiles at some distant view, and likely accelerates past the immediate neighborhood.

This use of the automobile as totem was not just part of the mythology that the National Association of Manufacturers cooked up. The car was a companion and a vehicle for progress for those who dwelt in the buildings surrounding the billboards, though no doubt they acutely felt the tension between the billboard’s messaging and their own personal struggles. And yet, in town and country, they relied on cars and trucks to live; the migrant laborers everywhere boarded vehicles to get to their next crop and to transport their families to the next place. But their view was ambiguous—the car was an implement, a nuisance needing repair, but also a vehicle of desire and dreams. The car fit into the meaning of what it was to be American, though most citizen’s version was less Simonized than that of the National Association of Manufacturers.

Rothstein used the car as a frame for the family as well—the American migrant family. In Oklahoma, probably in May 1936, Rothstein took a family portrait of four children and their mother. Their father is absent. The two youngest children—a girl and a boy (holding scissors)—look out through the car’s rear door window, as though posed in a picture frame. Three other girls’ heads float near corners of the open window. The eldest, her face reserved and serious, stands back, her hand touching her face; in the opposite corner, another girl smiles, elbows held high, hands caressing her neck. With this photograph Rothstein portrayed another family through a car window, one that contrasts with the caricature of the NAM billboard’s family. His complex and sensitive composition pulls the family together in a frame that itself contains a frame lent by a car.

These images of the migrant’s bed and the American families framed in car windows suggest the mark that the automobile has made on the national psyche. The car was knit into the fabric of citizenship and everyday life. The images show how the car—the most important technology of the twentieth century—could become such a component of our culture that it became emotionally enmeshed with ideals of freedom and independence.

Yes, a century ago cars drove the American Way. They still do.

Notes

[1] The two pictures share the title “Room in which migratory agricultural workers sleep. Camden County, New Jersey,” but I am quite sure that one of them was mislabeled in the Library of Congress catalogue or perhaps in the records of the Farm Security Administration. It is also likely that they were not taken in the same building, as the identical titles might lead one to believe. In fact, I think it’s likely that they weren’t even taken in the same New Jersey county. The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, at the New York Public Library also holds the Rothstein of the migrant’s bed with car decorations (https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/518bdec0-b97b-0138-ebbc-059ac310b610), but that NYPL digital record also includes the reverse side of the print. Typewritten on the back of the print is “Interior of migrant potatoe [sic] picker’s shack, Monmoth [sic], New Jersey October 1938.” That title is probably the one that Rothstein assigned to the print; the LC record is incorrect.

[2] Besides Rothstein, Dorothea Lange, John Vachon, Edwin Locke and Margaret Bourke-White used the NAM billboard campaign as an effective foil to emphasize its contrasts with real life circumstances. Bourke-White’s photographs of the aftermath of flooding in Louisville (January 1937) are particularly striking. For a discussion of some billboard-related FSA images, including the NAM campaign, see Bridgers, Jeff. “Signs of Their Times: The American Way” Picture This. The Library of Congress, November 27, 2015. https://blogs.loc.gov/picturethis/2015/11/signs-of-their-times-the-american-way.

For the bibliographically curious: The Library of Congress Online Catalogue, Prints and Photographs Division includes nearly 14,000 of Arthur Rothstein’s photographs he took for the Farm Security Administration (https://www.loc.gov/search/?fa=contributor:rothstein,+arthur&sp=3). Roy Stryker, the head of the Historical Section of the FAS where Arthur Rothstein worked, had a habit of punching holes in negatives that he deemed flawed—an act of censorship that was called “killing” a photograph. (The LC collections still contain some of them, for example, here.) According to Bill McDowell, they are actually new creations, some of which he gathered in McDowell, William H. and USA, eds. Ground: A Reprise of Photographs from the Farm Security Administration. Hillsborough, N.C.: Daylight, 2016. For a contemporary discussion of migrant farm labor in the 1930s and 1940s, see Ducoff, Louis J. “Migratory Farm Workers in the United States.” Journal of Farm Economics 29, no. 3 (August 1944): 711–22. https://doi.org/10.2307/1232909. Changes in the migrant worker population is somewhat clouded by the different methods of counting in the 1930 and 1940 censuses as well as the marked changes in the overall workforce after US involvement in World War II. Ducoff provides a good overview. National Book Award and Pulitzer Prize winner George Packer wrote a short introduction for this book of Rothstein’s photographs: Rothstein, Arthur. The Photographs of Arthur Rothstein. Fields of Vision. Washington, D.C: Library of Congress, 2011. Packer tells of an interview that Richard Dowd of the Smithsonian had with Rothstein in 1964. During the interview, Packer wrote, “Rothstein wondered why every twenty-five years, photographers couldn’t go out again and create ‘a record of what the United States is like, what life is like in the United States.’ Nearly two additional quarter centuries have passed since that interview.” That was in 2011; actually, today it’s well over two quarter centuries ago.