by Barbara Fischkin

Since its debut in 2013, I have been a fan of “By the Book,” a “Q and A” feature, in The New York Times Book Review. Google AI describes it as a look into “select authors’ reading habits and favorite books.” I’d always been so eager to read the text, that it was only recently I noticed the pun in the title. A word play on a phrase I had used umpteenth times to push sales, after the first of my three books was published in 1997. Duh.

Late last year one of those “select, authors did a slight stumble over the often-posed question about who to invite to a literary dinner party. He said he had been reading the feature for years—which I took as a big hint that he had long hoped to be a subject one day. I don’t know any writers who wouldn’t jump at the chance, myself included.

For me, one major problem: My last book was published in 2006, seven years before this feature appeared. Like many writers, my heart and soul are joyous about my successes yet tainted with bitterness and blame. In regard to my lack of a fourth book, I blame the editor—and supposed friend—who refused to acquire an in-depth look at the children of the autism surge growing into adulthood, as was my elder son. A similar tome, written by Washington insiders, was a Pulitzer prize finalist. With a little less bite, I blame the handful of non-writers with great stories, who chickened out when it came to partnering with me to write their books. To be fair they did this after editing, book proposals and early chapters were written—and after they paid me for my work. But when it came to publicly telling their stories, they got cold feet.

Most of all, though, I blame my current obscurity on myself and on a manuscript-creature titled The Digger Resistance. My yet unborn historical novel. Read more »

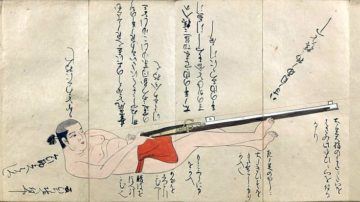

As the saying goes, if you believe only fascists guard borders, then you will ensure that only fascists will guard borders. The same principle applies to scientists working on nuclear weapons. If you believe that only Strangelovian warmongers work on nuclear weapons, you run the risk of ensuring that only such characters will do it.

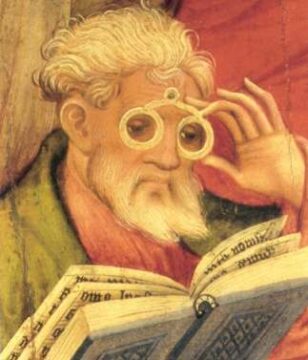

As the saying goes, if you believe only fascists guard borders, then you will ensure that only fascists will guard borders. The same principle applies to scientists working on nuclear weapons. If you believe that only Strangelovian warmongers work on nuclear weapons, you run the risk of ensuring that only such characters will do it. I’m haunted by the enormity of all of that which I’ll never read. This need not be a fear related to those things that nobody can ever read, the missing works of Aeschylus and Euripides, the lost poems of Homer; or, those works that were to have been written but which the author neglected to pen, such as Milton’s Arthurian epic. Nor am I even really referring to those titles which I’m expected to have read, but which I doubt I’ll ever get around to flipping through (In Search of Lost Time, Anna Karenina, etc.), and to which my lack of guilt induces more guilt than it does the real thing. No, my anxiety is born from the physical, material, fleshy, thingness of the actual books on my shelves, and my night-stand, and stacked up on the floor of my car’s backseat or wedged next to Trader Joe’s bags and empty pop bottles in my trunk. Like any irredeemable bibliophile, my house is filled with more books than I could ever credibly hope to read before I die (even assuming a relatively long life, which I’m not).

I’m haunted by the enormity of all of that which I’ll never read. This need not be a fear related to those things that nobody can ever read, the missing works of Aeschylus and Euripides, the lost poems of Homer; or, those works that were to have been written but which the author neglected to pen, such as Milton’s Arthurian epic. Nor am I even really referring to those titles which I’m expected to have read, but which I doubt I’ll ever get around to flipping through (In Search of Lost Time, Anna Karenina, etc.), and to which my lack of guilt induces more guilt than it does the real thing. No, my anxiety is born from the physical, material, fleshy, thingness of the actual books on my shelves, and my night-stand, and stacked up on the floor of my car’s backseat or wedged next to Trader Joe’s bags and empty pop bottles in my trunk. Like any irredeemable bibliophile, my house is filled with more books than I could ever credibly hope to read before I die (even assuming a relatively long life, which I’m not).

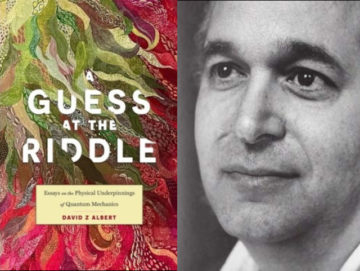

Physicists writing books for the public have faced a longstanding challenge. Either they can write purely popular accounts that explain physics through metaphors and pop culture analogies but then risk oversimplifying key concepts, or they can get into a great deal of technical detail and risk making the book opaque to most readers without specialized training. All scientists face this challenge, but for physicists it’s particularly acute because of the mathematical nature of their field. Especially if you want to explain the two towering achievements of physics, quantum mechanics and general relativity, you can’t really get away from the math. It seems that physicists are stuck between a rock and a hard place: include math and, as the popular belief goes, every equation risks cutting their readership by half or, exclude math and deprive readers of a deeper understanding. The big question for a physicist who wants to communicate the great ideas of physics to a lay audience without entirely skipping the technical detail thus is, is there a middle ground?

Physicists writing books for the public have faced a longstanding challenge. Either they can write purely popular accounts that explain physics through metaphors and pop culture analogies but then risk oversimplifying key concepts, or they can get into a great deal of technical detail and risk making the book opaque to most readers without specialized training. All scientists face this challenge, but for physicists it’s particularly acute because of the mathematical nature of their field. Especially if you want to explain the two towering achievements of physics, quantum mechanics and general relativity, you can’t really get away from the math. It seems that physicists are stuck between a rock and a hard place: include math and, as the popular belief goes, every equation risks cutting their readership by half or, exclude math and deprive readers of a deeper understanding. The big question for a physicist who wants to communicate the great ideas of physics to a lay audience without entirely skipping the technical detail thus is, is there a middle ground?

Religion has always had an uneasy relationship with money-making. A lot of religions, at least in principle, are about charity and self-improvement. Money does not directly figure in seeking either of these goals. Yet one has to contend with the stark fact that over the last 500 years or so, Europe and the United States in particular acquired wealth and enabled a rise in people’s standard of living to an extent that was unprecedented in human history. And during the same period, while religiosity in these countries varied there is no doubt, especially in Europe, that religion played a role in people’s everyday lives whose centrality would be hard to imagine today. Could the rise of religion in first Europe and then the United States somehow be connected with the rise of money and especially the free-market system that has brought not just prosperity but freedom to so many of these nations’ citizens? Benjamin Friedman who is a professor of political economy at Harvard explores this fascinating connection in his book “Religion and the Rise of Capitalism”. The book is a masterclass on understanding the improbable links between the most secular country in the world and the most economically developed one.

Religion has always had an uneasy relationship with money-making. A lot of religions, at least in principle, are about charity and self-improvement. Money does not directly figure in seeking either of these goals. Yet one has to contend with the stark fact that over the last 500 years or so, Europe and the United States in particular acquired wealth and enabled a rise in people’s standard of living to an extent that was unprecedented in human history. And during the same period, while religiosity in these countries varied there is no doubt, especially in Europe, that religion played a role in people’s everyday lives whose centrality would be hard to imagine today. Could the rise of religion in first Europe and then the United States somehow be connected with the rise of money and especially the free-market system that has brought not just prosperity but freedom to so many of these nations’ citizens? Benjamin Friedman who is a professor of political economy at Harvard explores this fascinating connection in his book “Religion and the Rise of Capitalism”. The book is a masterclass on understanding the improbable links between the most secular country in the world and the most economically developed one. Throughout history there have been prophets of doom and prophets of hope. The prophets of doom are often more visible; the prophets of hope are often more important. The Danish economist Bjorn Lomborg is a prophet of hope. For more than ten years he has been questioning the consensus associated with global warming. Lomborg is not a global warming denier but is a skeptic and realist. He does not question the basic facts of global warming or the contribution of human activity to it. He does not deny that global warming will have some bad effects. But he does question the exaggerated claims, he does question whether it’s the only problem worth addressing, he certainly questions the intense politicization of the issue that makes rational discussion hard and he is critical of the measures being proposed by world governments at the expense of better and cheaper ones. Lomborg is a skeptic who respects the other side’s arguments and tries to refute them with data.

Throughout history there have been prophets of doom and prophets of hope. The prophets of doom are often more visible; the prophets of hope are often more important. The Danish economist Bjorn Lomborg is a prophet of hope. For more than ten years he has been questioning the consensus associated with global warming. Lomborg is not a global warming denier but is a skeptic and realist. He does not question the basic facts of global warming or the contribution of human activity to it. He does not deny that global warming will have some bad effects. But he does question the exaggerated claims, he does question whether it’s the only problem worth addressing, he certainly questions the intense politicization of the issue that makes rational discussion hard and he is critical of the measures being proposed by world governments at the expense of better and cheaper ones. Lomborg is a skeptic who respects the other side’s arguments and tries to refute them with data.