by Mark Harvey

I would go home to eat, but I could not make myself eat much; and my father and mother thought that I was sick yet; but I was not. I was only homesick for the place where I had been. –Black Elk

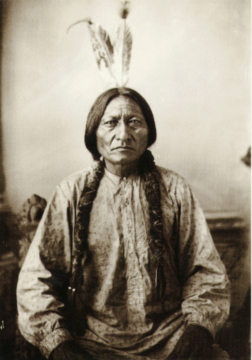

According to Lakota Indians, in early June of 1876, the great tribal chief Sitting Bull performed a sun dance in which he cut 100 pieces of flesh from his arms as an offering to his creator and then danced for a day and a half. He danced until he was exhausted from the dancing and the loss of blood and then fell into a vision of the coming battle with General George Custer at Little Big Horn. Moved by his vision, thousands of Cheyenne, Lakota, and Arapahoe warriors attacked Custer’s 7th Cavalry Regiment on June 25th, 1876, and overwhelmingly defeated it in what is today southeastern Montana. In the battle, Custer, two of his brothers, and a nephew were killed along with 265 other soldiers.

The battle was inevitable. The Bureau of Indian Affairs had insisted that the Lakota remove to a reservation by January 31, 1876, to accommodate white miners and settlers in the area. The Indians hated the idea of living on a reservation and giving up their life of hunting on the great plains so they refused to move to the reservation. Custer was sent by General Alfred Terry to pursue Sitting Bull’s people from the south and push them north to what would be a sort of ambush. But the brash young Custer far underestimated the number of Indians gathered near the Powder River and also their ferocious resolve to fight his regiment.

When I was a child, my family and school took us on trips throughout the southwest to visit Indian country like Mesa Verde in southern Colorado, the Navajo Nation in Arizona, and the Taos Pueblo in New Mexico. The trips were always enthralling, but we really didn’t get to know any Indians. When I played baseball as a kid against the team from Meeker, Colorado, I had no clue that about 100 years prior and a short 20 miles north of the baseball diamond, the US cavalry and the Ute Indians had fought a ferocious battle at Milk Creek. When I found arrowheads throughout western Colorado, I didn’t know which tribe had made them or where they got the obsidian stone.

But as little as I knew about Indians, I always had great admiration for them. To me as a child, they looked different in the way they held themselves. So I’d read what I could about them, and then carve bows and arrows out of willow trees, and silently stalk the woods trying to be what I thought was an Indian. Trying to be something that I had picked up out of children’s books.

I suppose I should begin here by addressing the use of the word Indian versus Native American. I use them interchangeably because that’s what my Native American friends tell me to do: that either term is accepted by some and rejected by others. While Native American is considered politically correct by many in the white community, some Indians consider it just another name coined by white people as a form of virtue-signaling. What seems to be universal is that each tribe prefers to be called by their tribal name rather than something all-encompassing. The Dine prefer to be called Dine, the Lakota like to be called Lakota, and the Chahta, Chahta. Maybe what’s more important as outsiders is an attempt at learning and understanding the past and current conditions of American Indians.

Here we are in the year 2023, and most of us have little understanding of the various American Indian nations around the country or of the urban Indian population. Close to 70 percent of American Indians live in or near cities. There are lots of vast generalities about how they lived, how they were treated, and where and how they live today. As someone who is interested in their history and lives, I recognize my own lack of knowledge, even as I follow some of the issues in the federal courts, through reading some of their journals and through travel.

There are more than 500 tribes living in America today so trying to understand their history and contemporary lives is an endless, captivating journey. Plenty of good books have been written by Indians and non-Indians alike to help us on that journey. In Black Elk Speaks, the writer and poet John G. Neihardt records the memories of the Lakota tribesman Nicholas Black Elk, giving us a glimpse of his spiritual world and his time with Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse. In Lakota Woman, Mary Brave Bird shares her life on the Rosebud reservation in the 1960s and 1970s and shares stories of the harsh life many Indian women experience today. In House Made of Dawn, the novelist Scott Momaday takes us on the journey of a young Indian from New Mexico caught between the old world of his grandfather and the new world of modern America.

If you really want a detailed account of both the abuses of Indians by the federal government as well as some unexpected sympathy by federal Indian agents stationed in the most remote regions, you might want to read the annual reports issued by The Bureau of Indian Affairs. The Bureau of Indian Affairs was formed in 1824 by then Secretary of War John Calhoun. But its origins go back to 1775 when Congress formed the Committee on Indian Affairs. Ben Franklin was its first head. On paper, the agency was meant to handle treaties between the US government and the hundreds of tribes around the country and also to handle the strained and often violent encounters between white settlers and Indians. But the real intent of the BIA in its early years was to deal with what was called “The Indian Question” or “The Indian Problem,” whose phrasing has an ugly resemblance to the “Jewish Question.”

The early annual reports issued by the Commissioner of Indian Affairs ooze with contempt for Native Americans. For instance, the introduction to the 1876 report, written by then-commissioner John Quincy Smith the year Custer was killed, reads in part,

The management of Indian affairs is always attended with much difficulty and embarrassment. In every other department of the public service, the officers of the Government conduct business mainly with civilized and intelligent men. The Indian Office, in representing the Government, has to deal mainly with an uncivilized and unintelligent people, whose ignorance, superstition, and suspicion materially increase the difficulty both of controlling and assisting them.

That year Smith was working on removing Indians from Colorado, Utah, New Mexico, and Arizona to relocate them to “Indian Territory.” Indian Territory was a somewhat vague term and unincorporated. But it primarily referred to what is today Oklahoma. Smith’s report is long on complaints about lacking the congressional appropriations to do all his removing and “civilizing” and Christianizing of Indians. His language has the tone of an exterminator intent on ridding the nation of pests. He writes, “If they cannot be taught, and taught very soon, to accept the necessities of their situation and begin in earnest to provide for their own wants by labor in civilized pursuits, they are destined for speedy extinction.”

Smith believed that all Indians should be removed from lands being settled by whites and concentrated on just a few reservations. He had his eye on the Indian Territory of Oklahoma, the Yakama reservation in Washington, and the White Earth reservation in northern Minnesota for relocation. Throughout the report, his favorite word seems to be “remove.” Remove the Indians from Kansas, remove the Indians from Wyoming, remove the Indians from Nebraska, remove the Indians from Colorado, remove the Indians from New Mexico, remove the Indians from Utah, and remove the Indians from Arizona.

What’s interesting in reading the same report in which Smith so disparages Indians with a broad brush is that various of the white men under Smith’s authority and working directly with tribes in remote territories—Indian agents as they’re called—write about their experiences in an entirely different light. There is far less contempt and in many cases, admiration and empathy for the tribes undergoing removal or those having recently been placed on reservations.

In describing his experience with the Ute Indians, E.H. Danforth, the Indian agent in what is now Meeker, Colorado, wrote,

Of the conduct of the Indians away from the agency, when they meet with white settlers, I cannot, of course, judge so fully, and assert so confidently; but I am satisfied that it has been, almost without exception, good…. I find that generally the most complaint is made by persons who have the least cause for it; that stories of insolence and violence of these Indians, originate most frequently among those who have never experienced such, but who, on the contrary, have abused, and maltreated them;

The following year Danforth wrote a letter to Smith defending the boundaries of the Ute reservation from white settlers and prospectors intent on moving into what Danforth considered Ute territory. In the letter, Danforth notes that according to treaty, the northern boundary of the Ute reservation should be 15 miles north of the 40th parallel but that the surveyor had placed the boundary 2 ½ miles south of the 40th parallel, a 17 ½ mile mistake. He goes on to write, “I ask whether I will be supported if I endeavor to remove persons coming upon the reserve to settle or to “prospect”; and where I am to look for assistance to do so. This has to have been one of the very few times in the 19th century when the word “remove” was aimed at white men instead of Indians.

By 1877, Smith had been replaced as commissioner by Ezra Hayt. Hayt was just as intent on “civilizing” Indians as Smith and certainly considered them savages. In his 1877 annual report, he wrote,

The Indian, in his savage state, is the only born aristocrat on American soil. He despises labor and looks upon it as an indignity. He will hunt or make war at an immense expenditure of great strength, and in the prosecution of those pursuits he will exhibit great tenacity of purpose; but when he is talked to about the necessity of toil, as a means to earn his bread legitimately, he turns a deaf ear, and imposes on his squaw, the burden and drudgery of work.

There is great irony in Hayt’s consideration of how Indians lived on the land and his judgment of their character. For one of the tribes under the “authority” of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs was the Mojave, a people who had lived along the Colorado River in Arizona and California for what archaeologists estimate to be around 12,000 years. To survive 12,000 years in that harsh desert setting suggests that maybe our Native American forebears knew something of toil and labor and how to live in a particular geography.

At the time Hayt wrote his report with his scalding comments on Native Americans, American whites had barely set foot in Arizona and California. In the hundred-fifty or so years since our early settlements, the jury is out as to whether our particular style of “civilization” along the Colorado River will last even a thousand years. With the recent water wars among the seven states dependent on the Colorado River, one might be forgiven to think otherwise.

As was the case under Commissioner Smith’s reign, Indian agents working under Hayt expressed sentiments entirely counter to his. In the very first agent-entry in the 1877 annual report, W.E. Morford, head of the Colorado River Reservation in Arizona, writes, “In fact, more harm has been done to these poor Indians by the Government, within the past year and a half, than can be overcome in five years.”

It’s taken many years to acknowledge our brutal treatment of the millions of Indians who once roamed the nation from Maine to California and of course, Alaska. That repeated use of the word “removal” in the various annual reports from the Commissioners of Indian Affairs is such a sanitized word to describe a near eradication of a people.

The Bureau of Indian Affairs has evolved considerably since its days as essentially an Indian removal operation. For one thing, its leadership is now made of Indians. The Assistant Secretary, Bryan Newland, is Ojibwe, the Director, Darryl LaCounte, is of the Turtle Mountain Band from the Chippewa, and the other two directors are Native American as well. To its credit, the BIA website acknowledges its past and promises a new charter with the words, “The BIA has changed dramatically over the past 185 years, evolving as Federal policies designed to subjugate and assimilate American Indians and Alaska Natives have changed to policies that promote Indian self-determination.”

The website speaks of justice, safety, and sovereignty for Indians, along with climate resilience, economic programs, and fire management. A far cry from the words and actions of commissioners like John Quincy Smith or Ezra Hayt. But even today, the BIA does not always come down on the side of Indians and the agency sometimes appears to still have one foot in the 19th century. For instance, in 2006 when the City of Las Vegas attempted a huge water grab that would likely dry up the Swamp Cedars, a sacred ground to the Goshutes, Western Shoshone, and Paiute tribes, the BIA negotiated a backroom deal endorsing the City of Las Vegas plans without consulting any of the tribes. In a very recent case brought before the Supreme Court, Arizona v Navajo Nation, over Navajo water rights on the Colorado River, the BIA was on the side of Arizona. I still don’t get that one.

To be ripped from the homes and hunting grounds of hundreds or thousands of years, relocated to Oklahoma or Yakima, or Utah, Christianized and “civilized,” has to leave a cultural and spiritual wound that will need years and years to fully heal. But in the Indian journals I read, there is a healthy defiance in wanting to heal and never be considered broken. In The American Indian Quarterly, Ricki Ginsberg and Wendy J. Glenn write about how modern Choctaw women have re-walked The Trail of Tears as a way to “speak back and combat shame.” In the same article, they stress the importance of art and storytelling as “enduring weapons against colonial erasure, a reclamation, a revitalization.” This reclaiming of their history and sovereignty, people to people, tribe to tribe, nation to nation, is a continental movement that runs through their writing, their art, the federal courts, and the voting booths.

The spirit of Sitting Bull’s long, hard Sun Dance and immense vision continues.