by Barbara Fischkin

Since its debut in 2013, I have been a fan of “By the Book,” a “Q and A” feature, in The New York Times Book Review. Google AI describes it as a look into “select authors’ reading habits and favorite books.” I’d always been so eager to read the text, that it was only recently I noticed the pun in the title. A word play on a phrase I had used umpteenth times to push sales, after the first of my three books was published in 1997. Duh.

Late last year one of those “select, authors did a slight stumble over the often-posed question about who to invite to a literary dinner party. He said he had been reading the feature for years—which I took as a big hint that he had long hoped to be a subject one day. I don’t know any writers who wouldn’t jump at the chance, myself included.

For me, one major problem: My last book was published in 2006, seven years before this feature appeared. Like many writers, my heart and soul are joyous about my successes yet tainted with bitterness and blame. In regard to my lack of a fourth book, I blame the editor—and supposed friend—who refused to acquire an in-depth look at the children of the autism surge growing into adulthood, as was my elder son. A similar tome, written by Washington insiders, was a Pulitzer prize finalist. With a little less bite, I blame the handful of non-writers with great stories, who chickened out when it came to partnering with me to write their books. To be fair they did this after editing, book proposals and early chapters were written—and after they paid me for my work. But when it came to publicly telling their stories, they got cold feet.

Most of all, though, I blame my current obscurity on myself and on a manuscript-creature titled The Digger Resistance. My yet unborn historical novel. Read more »

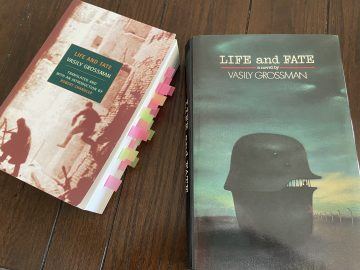

On June 22, 1941, Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union in a typhoon of steel and firepower without precedent in history. In spite of telltale signs and repeated warnings, Joseph Stalin who had indulged in wishful thinking was caught completely off guard. He was so stunned that he became almost catatonic, shutting himself in his dacha, not even coming out to make a formal announcement. It was days later that he regained his composure and spoke to the nation from the heart, awakening a decrepit albeit enormous war machine that would change the fate of tens of millions forever. By this time, the German juggernaut had advanced almost to the doors of Moscow, and the Soviet Union threw everything that it had to stop Hitler from breaking down the door and bringing the whole rotten structure on the Russian people’s heads, as the Führer had boasted of doing.

On June 22, 1941, Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union in a typhoon of steel and firepower without precedent in history. In spite of telltale signs and repeated warnings, Joseph Stalin who had indulged in wishful thinking was caught completely off guard. He was so stunned that he became almost catatonic, shutting himself in his dacha, not even coming out to make a formal announcement. It was days later that he regained his composure and spoke to the nation from the heart, awakening a decrepit albeit enormous war machine that would change the fate of tens of millions forever. By this time, the German juggernaut had advanced almost to the doors of Moscow, and the Soviet Union threw everything that it had to stop Hitler from breaking down the door and bringing the whole rotten structure on the Russian people’s heads, as the Führer had boasted of doing.

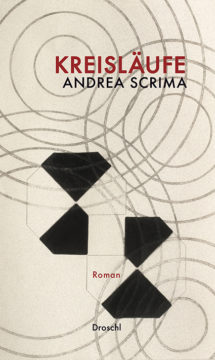

Novels set in New York and Berlin of the 1980s and 1990s, in other words, just as subculture was at its apogee and the first major gentrification waves in various neighborhoods of the two cities were underway—particularly when they also try to tell the coming-of-age story of a young art student maturing into an artist—these novels run the risk of digressing into art scene cameos and excursions on drug excess. In her novel A Lesser Day (Spuyten Duyvil, second edition 2018), Andrea Scrima purposely avoids effects of this kind. Instead, she concentrates on quietly capturing moments that illuminate her narrator’s ties to the locations she’s lived in and the lives she’s lived there.

Novels set in New York and Berlin of the 1980s and 1990s, in other words, just as subculture was at its apogee and the first major gentrification waves in various neighborhoods of the two cities were underway—particularly when they also try to tell the coming-of-age story of a young art student maturing into an artist—these novels run the risk of digressing into art scene cameos and excursions on drug excess. In her novel A Lesser Day (Spuyten Duyvil, second edition 2018), Andrea Scrima purposely avoids effects of this kind. Instead, she concentrates on quietly capturing moments that illuminate her narrator’s ties to the locations she’s lived in and the lives she’s lived there.