by Mark Harvey

The biggest hazard on my one trip to Minneapolis was being invited to too many family picnics and possibly dying from an overdose of mayonnaise. You have to go to Minnesota to really experience what’s known in the vernacular as Minnesota Nice. The term springs from the sincere desire those northern people have that you’ll take a second helping of bratwurst and potato salad, then get home safely, and call your host or your family when you do. It’s kind of wonderful and kind of smothering, akin to having one too many comforters on your bed.

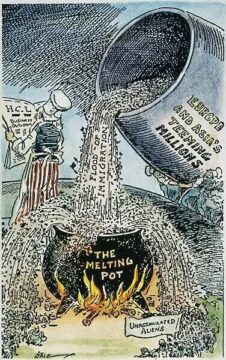

So I don’t think too many of us were expecting Minnesota to be our modern-day Gettysburg, when all those nice people came out onto the streets to fight Trump’s reviled brand of fascism. Minnesota was largely out of my news feed until these past few weeks when the jackbooted thugs from ICE began to tear apart the famously neighborly city of Minneapolis. Occasionally I’d hear about a brutal cold front coming down from the arctic or an exceptional year for the Vikings, but there just weren’t that many sensational stories coming down from the Land-O-Lakes.

Before Trump and Kristi Noem sent their band of thugs up to Minnesota, the people there were busy carrying on what appeared to be, on the whole, enviable lives. Statistics never tell the whole story, but when it comes to quality of life, Minnesota consistently ranks in the top five US States based on metrics like poverty levels, health care, safety, education, and fiscal stability. Its consistently high safety ranking—factors like crime rates, quality of hospitals, quality of roads, and speed of emergency medical services—certainly took a blow when the masked goons dispatched to “make cities safe again,” showed up and wiped their boots on the Constitution.

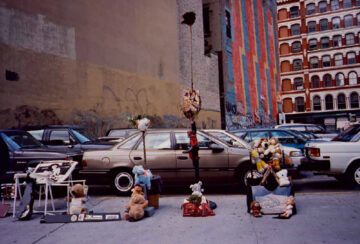

We all saw the grotesque murders of Renee Good, a young mother, and Alex Pretti, a young ICU nurse, by trigger-happy ICE agents just weeks apart from each other. Even with all the other violence going on in the world—Ukraine, Gaza, and the rest—those murders were hard to watch. Whether it was the stuffed animals in Good’s car or the mournful version of Taps played as co-workers wheeled Pretti’s coffin down the hall of the Vets’ Hospital where he worked, there were poignant emblems and imagery reminding us that those two never should have been shot dead. Read more »

3QD: The old cliché about a guest needing no introduction never seemed more apt. So instead of me introducing you to our readers, maybe you could begin by telling us a little bit about yourself, perhaps something not so well known, a little more revealing.

3QD: The old cliché about a guest needing no introduction never seemed more apt. So instead of me introducing you to our readers, maybe you could begin by telling us a little bit about yourself, perhaps something not so well known, a little more revealing.

Last spring, American documentary film maker Ken Burns gave a commencement address at Brandeis University in Boston. Burns is a talented speaker, adept at spinning uplifting yarns, and

Last spring, American documentary film maker Ken Burns gave a commencement address at Brandeis University in Boston. Burns is a talented speaker, adept at spinning uplifting yarns, and

In daily life we get along okay without what we call thinking. Indeed, most of the time we do our daily round without anything coming to our conscious mind – muscle memory and routines get us through the morning rituals of washing and making coffee. And when we do need to bring something to mind, to think about it, it’s often not felt to cause a lot of friction: where did I put my glasses? When does the train leave? and so on.

In daily life we get along okay without what we call thinking. Indeed, most of the time we do our daily round without anything coming to our conscious mind – muscle memory and routines get us through the morning rituals of washing and making coffee. And when we do need to bring something to mind, to think about it, it’s often not felt to cause a lot of friction: where did I put my glasses? When does the train leave? and so on. In the game of chess, some of the greats will concede their most valuable pieces for a superior position on the board. In a 1994 game against the grandmaster Vladimir Kramnik, Gary Kasparov sacrificed his queen early in the game with a move that made no sense to a middling chess player like me. But a few moves later Kasparov won control of the center board and marched his pieces into an unstoppable array. Despite some desperate work to evade Kasparov’s scheme, Kramnik’s king was isolated and then trapped into checkmate by a rook and a knight.

In the game of chess, some of the greats will concede their most valuable pieces for a superior position on the board. In a 1994 game against the grandmaster Vladimir Kramnik, Gary Kasparov sacrificed his queen early in the game with a move that made no sense to a middling chess player like me. But a few moves later Kasparov won control of the center board and marched his pieces into an unstoppable array. Despite some desperate work to evade Kasparov’s scheme, Kramnik’s king was isolated and then trapped into checkmate by a rook and a knight.

What do we know about vampires?

What do we know about vampires?