by Mark Harvey

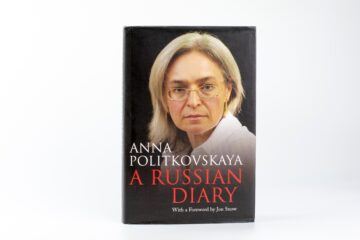

On September 1, 2004, a middle-aged Russian journalist named Anna Politkovskaya boarded a plane in Moscow on her way to Ossetia to cover a hostage crisis in the town of Beslan. During the flight, she drank a cup of tea that almost killed her. After she drank the tea, she became disoriented, began to vomit, and ultimately lost consciousness. She was taken to a hospital in Rostov-on-Don, where doctors concluded she had been poisoned.

Politkovskaya had been reporting on the human rights abuses in Russia and Chechnya for some time and was a harsh critic of Vladimir Putin. In one of her books she had written, “If you live in Russia, you cannot help but notice that Putin’s Russia is a world of violence, lies, and injustice.”

Throughout her career, Politkovskaya received death threats and was heavily surveilled by the Russian government. But the intimidation didn’t stop her, and she wrote hundreds of articles for the independent newspaper Novaya Gazeta and several books highly critical of Putin. In her 2004 book, Putin’s Russia, she bravely wrote about the corruption, human rights abuses, and oligarchy in Russia with an unflinching style.

In short, she was a daring, hardworking investigative journalist who risked her life to write about the cruel and criminal aspects of Russia. She was assassinated in the elevator of her apartment building on October 7, 2006—Vladimir Putin’s birthday. Read more »