by Herbert Harris

The greatest privilege of my childhood was growing up in a house where books had their own room.

My father’s library occupied the second floor, the only room without a window air-conditioning unit. On summer afternoons in Washington, DC, when the heat and humidity pressed down like a weight, the rest of the house hummed and rattled with machines straining to keep up. The air in the library stayed stubbornly still. It was the early 1970s, and I was on summer break after tenth grade, retreating there to find the peculiar solitude this room alone offered. Each book I opened sent up a cloud of dust that glittered in the angled sunlight. Shutting the door turned the room into a sauna, but in that quiet stillness, I didn’t mind. It felt like the price of admission to a different world.

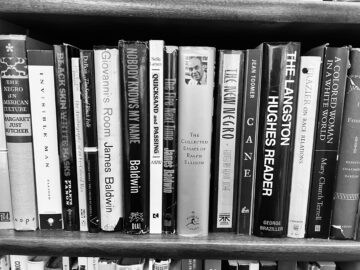

The previous summer had unfolded differently. I had just finished ninth grade, where we surveyed the classics of English literature and retraced the decisive moments of Western civilization, reliving the deeds of its great men and women. I spent long afternoons in the library, sinking into those books as the heat pooled around me. I melted into a reclining chair and wandered through the past. That immersion had felt complete, even sufficient. But this summer, I arrived with a different appetite. I was growing skeptical of the Eurocentric narratives threaded through everything I was learning. I sensed there were other stories and vantage points, and I came looking for them.

I picked up the book I had been reading a few days earlier and turned to the page marked with an index card. I searched for the sentence I remembered, but at first the words slipped past me. James Baldwin was writing about a Swiss village, about children shouting “Neger” as he walked through the snow. Seeing the word on the page registered instantly, not as surprise but as recognition. I had learned early what it meant to be called that name in its American form. That knowledge had settled into my body long before I could articulate it. Read more »

Orwell has surely been safe for ages – through just two famous books, neither of which is Keep the Aspidistra Flying. His essays seem alive too. Ideology plays a role here: he was saying things in Animal Farm and 1984 that influential people wanted disseminated. You couldn’t get through school in Britain without being made to read him. I persist in thinking him overrated. Will he fade without the Cold War? There’s no sign of it yet.

Orwell has surely been safe for ages – through just two famous books, neither of which is Keep the Aspidistra Flying. His essays seem alive too. Ideology plays a role here: he was saying things in Animal Farm and 1984 that influential people wanted disseminated. You couldn’t get through school in Britain without being made to read him. I persist in thinking him overrated. Will he fade without the Cold War? There’s no sign of it yet.

About a third of the way through a first-year humanities honors course, one of my more engaged and talkative students pulled me aside after class for a private chat. She waited, clearly anxious, while the rest of her classmates filed out and then turned to me with her eyes already filling up with tears.

About a third of the way through a first-year humanities honors course, one of my more engaged and talkative students pulled me aside after class for a private chat. She waited, clearly anxious, while the rest of her classmates filed out and then turned to me with her eyes already filling up with tears. Now there is a

Now there is a

And then I started trying to warn people about the dangers of algorithms when we trust them blindly. I wrote a book called Weapons of Math Destruction, and in doing so I interviewed a series of teachers and principals who were being tested by this new-fangled algorithm called the value-added model for teachers. And it was high stakes. They were being denied tenure or even fired based on low scores, but nobody could explain their scores. Or shall I say, when I asked them, “Did you ask for an explanation of the score you got?” They often said, “Well, I asked, but they told me it was math and I wouldn’t understand it.”

And then I started trying to warn people about the dangers of algorithms when we trust them blindly. I wrote a book called Weapons of Math Destruction, and in doing so I interviewed a series of teachers and principals who were being tested by this new-fangled algorithm called the value-added model for teachers. And it was high stakes. They were being denied tenure or even fired based on low scores, but nobody could explain their scores. Or shall I say, when I asked them, “Did you ask for an explanation of the score you got?” They often said, “Well, I asked, but they told me it was math and I wouldn’t understand it.”

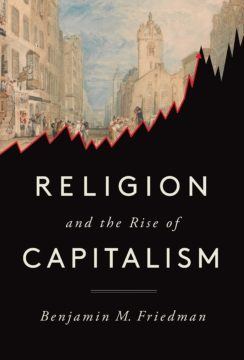

Religion has always had an uneasy relationship with money-making. A lot of religions, at least in principle, are about charity and self-improvement. Money does not directly figure in seeking either of these goals. Yet one has to contend with the stark fact that over the last 500 years or so, Europe and the United States in particular acquired wealth and enabled a rise in people’s standard of living to an extent that was unprecedented in human history. And during the same period, while religiosity in these countries varied there is no doubt, especially in Europe, that religion played a role in people’s everyday lives whose centrality would be hard to imagine today. Could the rise of religion in first Europe and then the United States somehow be connected with the rise of money and especially the free-market system that has brought not just prosperity but freedom to so many of these nations’ citizens? Benjamin Friedman who is a professor of political economy at Harvard explores this fascinating connection in his book “Religion and the Rise of Capitalism”. The book is a masterclass on understanding the improbable links between the most secular country in the world and the most economically developed one.

Religion has always had an uneasy relationship with money-making. A lot of religions, at least in principle, are about charity and self-improvement. Money does not directly figure in seeking either of these goals. Yet one has to contend with the stark fact that over the last 500 years or so, Europe and the United States in particular acquired wealth and enabled a rise in people’s standard of living to an extent that was unprecedented in human history. And during the same period, while religiosity in these countries varied there is no doubt, especially in Europe, that religion played a role in people’s everyday lives whose centrality would be hard to imagine today. Could the rise of religion in first Europe and then the United States somehow be connected with the rise of money and especially the free-market system that has brought not just prosperity but freedom to so many of these nations’ citizens? Benjamin Friedman who is a professor of political economy at Harvard explores this fascinating connection in his book “Religion and the Rise of Capitalism”. The book is a masterclass on understanding the improbable links between the most secular country in the world and the most economically developed one.

A few days ago I finished watching a new

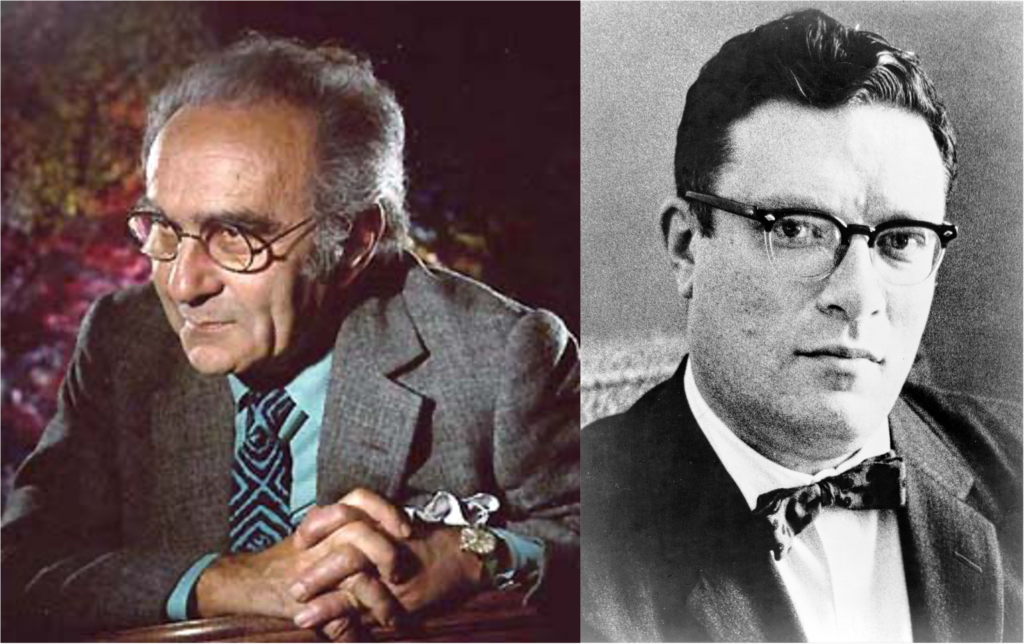

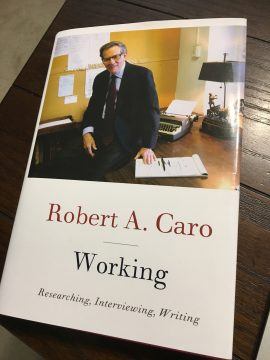

A few days ago I finished watching a new  Robert Caro might well go down in history as the greatest American biographer of all time. Through two monumental biographies, one of Robert Moses – perhaps the most powerful man in New York City’s history – and the other an epic multivolume treatment of the life and times of Lyndon Johnson – perhaps the president who wielded the greatest political power of any in American history – Caro has illuminated what power and especially political power is all about, and the lengths men will go to acquire and hold on to it. Part deep psychological profiles, part grand portraits of their times, Caro has made the men and the places and times indelible. His treatment of individuals, while as complete as any that can be found, is in some sense only a lens through which one understands the world at large, but because he is such an uncontested master of his trade, he makes the man indistinguishable from the time and place, so that understanding Robert Moses through “The Power Broker” effectively means understanding New York City in the first half of the 20th century, and understanding Lyndon Johnson through “The Years of Lyndon Johnson” effectively means understanding America in the mid 20th century.

Robert Caro might well go down in history as the greatest American biographer of all time. Through two monumental biographies, one of Robert Moses – perhaps the most powerful man in New York City’s history – and the other an epic multivolume treatment of the life and times of Lyndon Johnson – perhaps the president who wielded the greatest political power of any in American history – Caro has illuminated what power and especially political power is all about, and the lengths men will go to acquire and hold on to it. Part deep psychological profiles, part grand portraits of their times, Caro has made the men and the places and times indelible. His treatment of individuals, while as complete as any that can be found, is in some sense only a lens through which one understands the world at large, but because he is such an uncontested master of his trade, he makes the man indistinguishable from the time and place, so that understanding Robert Moses through “The Power Broker” effectively means understanding New York City in the first half of the 20th century, and understanding Lyndon Johnson through “The Years of Lyndon Johnson” effectively means understanding America in the mid 20th century. by Leanne Ogasawara

by Leanne Ogasawara