by Barbara Fischkin

Part One: Before Mari Saved Us

This is the back story: Maria Angeles Garcia, known to us as “Mari,” was a godsend to our family. In part two, which I plan to publish in May, readers will find out more about how this young, single mother from a small village in northern Mexico moved with us to, of all places, Hong Kong.

That move was in 1989. A few years earlier Mari had left her children with relatives with plans to earn money as a domestic worker in la capital, Mexico City—and then return home to give her family a better life. Eventually she came to work for us. Within a year, my husband was notified he would be transferred to Hong Kong. We asked Mari if she would come with us for a short while. We never expected her to say yes. But she did.

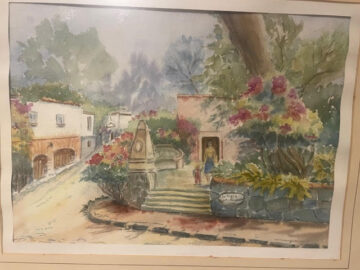

Mari grew up hearing both Spanish and an indigenous language. In Hong Kong, most people speak English and Cantonese. Regardless of geography, the underlying job wouldn’t change. When I was working as a journalist, from a home office or out doing interviews, I needed a nanny to take my first-born toddler son on small excursions. I didn’t want him locked behind the walls of our palatial home. I wanted him out and about, playing with neighborhood kids and savoring the bright colored flowers. I wanted him to suck oranges Mari picked right off the tree and to enjoy the aroma of elote— corn—roasting on sidewalk barbeques.

Mari knew that in Hong Kong, things would change. She mustered the courage, the fortitude and a free-range sensibility to spend a few months with us in Asia. She could have easily found another position in Mexico City. But she was intent on doing her job and frankly wanted to make sure our family, especially the child, transitioned safely.

After watching Mari in action, I knew so much more about assessing and hiring good household help. Typically, I did a good job. This chapter, though, is about the ones who came before Mari. Some had their moments of glory. Most get lost in her shadow.

Before my husband and I moved to Mexico City in 1987, I’d had little experience with household help and child care. In regard to other experiences, I’d had plenty. My husband and I had, as New York State-based newspaper reporters, covered the “war at home” such that it was among politicians and others on Long Island. Then we moved on to a real war in Northern Ireland, with stops to write stories in Latin America, ranging from immigration (mine) to Iran-Contra (his). We didn’t have regular or live-in household help, because we didn’t have much that would qualify as a house in need of help. We also didn’t have children back then, although both of us as young adults could have used a nanny or two. We rented on the north and south shores of Long Island. Before we married my husband bought a small bungalow, in what was then the slightly tawdry City of Long Beach. (I was his tenant, as well as his girlfriend. I paid the rent on time, although he never actually asked for it). In Dublin we rented, again. In Belfast we crashed with a family of Irish Nationalists, whom we met through connections with, well…let’s call them “idealistic rebels.” The Trainors of Belfast cleared out parts of their modest redbrick house on the Andersonstown Road so we felt at home. They cleaned that house themselves.

On Long Island and in Dublin I had what my mother used to call “cleaning ladies.” Or worse: “girls.” They came on-or-off schedule, every two weeks or so, worked quickly and left without much conversation. Only Gerri, who cleaned our Long Beach bungalow, brought her personal problems to work. I gave her extra money one day, and told her not to pay me back. She told me that no one in Long Beach had ever been so nice to her. Knowing the people of Long Beach, I didn’t believe this.

As for my mother, she had those “girls,” an ever-revolving coterie of women of color, who came when she tired of cleaning our own redbrick house on Avenue I in the Midwood section of Brooklyn. It was about the same size as the Trainor abode in Belfast. I think these “girls,” were sent by an agency. My mother often measured their abilities in comparison to her friends’ “girls,” as in “the girl I had today was even better than Mona Wolkoff’s.” (My mother idolized Mona Wolkoff.)

My mother would make each “girl” lunch, setting her pink and gray Formica kitchen table for the occasion. She typically served Campbell’s soup, tuna fish sandwiches on Wonder Bread and whatever cookies were around. I have the impression that serving lunch to “the girl” was customary back then.

My favorite among the “girls,” was the one who refused to eat my mother’s lunch because it was not kosher enough. Yes, the woman was Black. My mother was the Caucasian Ukrainian-born Jewish wife of the perpetual president of Congregation B’nai Israel of Midwood, located diagonally across the street. The shul was more Orthodox than we were. But my mother took great pride in keeping a kosher home. At first, she was insulted by the “girl’s” critique. Then, in her trademark fashion, she began her interrogation. I am not sure why I was home from school at lunchtime that day. But as I listened in, I learned with my mother that this particular “girl,” belonged to one of several historic communities of Black Jewish people in New York City. And hers, downtown in the Crown Heights area of Brooklyn, was very Orthodox.

Years later, I arrived in Mexico City well into my first pregnancy. My husband and I moved into a literal mansion in the tony San Angel neighborhood, walking distance from a home Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo kind of shared—they lived in two separate but connected houses. Newsday, my husband’s employer—and my former employer— had rented it for us for $1,500 US dollars a month. It had balconies, beautifully tiled bathrooms for each of three bedrooms upstairs—and a den and two more bathrooms and a sprawling office downstairs. The garden, which included a swing set and a swimming pool, resembled a park, Typical of many of these houses the living quarters were plushy; the kitchen and the “maids’ quarters” were a mess. With the landlady’s permission, I hired day laborers to paint and fix the maid’s corners to mitigate some of my guilt.

Somewhere along the line, it belatedly occurred to me that my home life was going to change in major ways. One “girl,”—in Mexico they called them “muchachas”—would not be nearly enough for a house this size. And then there was the baby on the way, coming in tandem with work assignments. I would need something I never dreamed of having, a nanny.

And, duh, there were maids’ quarters because all the helpers expected to live with us, as was the case in most of Mexico. I quickly realized I wasn’t just hiring staff; I was hiring housemates. The going rate for their salaries was about 25 US dollars a month, plus good food and marginal boarding conditions, despite the recent renovations. I couldn’t stand it. I offered prospective applicants $35-a-month and wanted to go higher. But already I had pissed off our house-rich neighbors who were “suffering” from a devaluation of the Mexican peso. Their household budgets had tightened. And in our neighborhood, everyone knew what everyone else paid their muchachas.

Enter Lilia, our first muchacha who insisted on being viewed as a “housekeeper.” This is known in Mexico as an “ama de llaves,” loosely translated as the mistress of the keys. Lilia also anointed herself the nanny for the baby who would soon arrive and then took it upon herself to hire and house an ever-revolving team, including a 15-year-old niece who became pregnant. Lilia was less a mistress of the keys than a keeper of the keys. She was my keeper as well. An expert at identifying my weaknesses, she bossed me around and took full advantage of my American desire to convince her to like me. Shouldn’t it have been the other way around? Probably. But by then I was a tired new mother with work to do in a foreign country. Lilia often had her “brother” Carlos stop in for a range of handyman work. Eventually I realized he was in our kitchen for every meal – including breakfast. I suspected he wasn’t a “brother” but a boyfriend and possibly a husband. I dared not ask.

At one point Lilia announced she had to leave for her real home, in one of Mexico City’s slums, because “Mayra,” the little daughter she’d left behind with relatives, needed a brain operation. This broke my heart. Lilia asked for $100 dollars, which seemed like a bargain rate for a neurosurgeon. I gave her the money. She appointed an assistant ama de llaves, said she’d be back when her daughter recovered and left (along with Carlos). A week later she returned pronouncing the operation a success, as she showed off her new and stylish white go-go boots, not quite worthy of Courrèges but definitely available for a hundred American dollars in a nice Mexico City shop. Besides the boots, she also had Carlos.

For a while it was easier to keep Lilia—and Carlos—working for me than to replace her. Lilia was good with my baby and an excellent cook. She was the devil I knew.

Then she did the unthinkable. She stole from me. I had no proof, just a feeling in my gut that this had happened. Some “good luck” cash my late mother had left for me went missing from an envelope in a bureau drawer, along with my mother’s last letter to me.

I fired Lilia and hired Mari in her place.

She was honest. And she was unburdened by any “Carlos.”