by Barbara Fischkin

I remember the day I realized that my cousin Bernard Moskowitz—my father’s nephew—was nothing like my other relatives.

The realization came in a flash as I spotted a newly arrived letter on the dining room table at our home at 4722 Avenue I in the Midwood section of Brooklyn. Two pages. Typewritten. It remains in my mind’s eye. I recognized the scratchy signature: It was my “Cousin Bernie.” I went back to the first page because that seemed like it was from somebody else It was embossed with these words:

Moorhead, Minnesota.

Professor B.B. Morris.

My mother, her eagle eyes in play, gazed through the opening from the kitchen and walked up behind me.

“Is this…,” I said

“Yes,” she replied, smiling. “Cousin Bernie got a good job. Daddy is so proud.” She paused. A worried look took over her face. “He changed his name. Maybe they don’t like Jews there.” Another pause. More worry. “It must be very cold.”

I imagined my mother sending Cousin Bernie a sweater. Or two. Or ten.

What else? A Star of David tie clip? A Hebrew prayer book? The possibilities were endless.

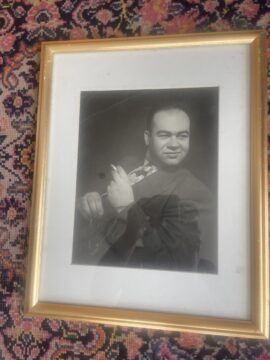

I was an adolescent on the day that letter arrived. All I really knew about Cousin Bernie was that my father adored him. For the life of me I couldn’t figure out why. Bernie was closer in age to the uncles on my mother’s side of the family—we were much closer to that side— than to any of my cousins. He visited infrequently and displayed none of the bon vivant nature of my maternal uncles—Al, Eli and Sammy. A wickedly handsome trio. Cousin Bernie was prematurely balding, bespeckled and a bit stout. People said he was the spitting image of my father—and this was true. Maybe that was why my father liked him so much.

As far as I was concerned, Cousin Bernie’s only claim to fame was that he was the only son of my father’s only sister. Boring. My parents told me Cousin Bernie’s mother was dead. This was somewhat more interesting. I was little the first time I asked what killed her. In response, my mother gave me a pail and a shovel and told me to go to the backyard and dig to China. I asked again when I was older and she ordered me to do my homework. For a family that thrived on stories and their accompanying minutiae, this silence was nearly unprecedented.

Then, during my adolescent years, that letter from the wilds of Minnesota arrived and my view of Cousin Bernie, even without any details about his dead mother, took over my imagination. Cousin Bernie had suddenly become very interesting, all on his own.

I had been to the Midwest, to Omaha with my mother to visit more of her relatives. I didn’t like it much. But a place named Moorhead, sounded distant, exotic, imbued with magic. Moorhead had changed Cousin Bernie into someone else. He was now B.B. Morris. Professor B. B. Morris. I considered that he might not be Jewish anymore. Just like Jesus, which was the only comparable example I knew. That Cousin Bernie looked more like Buddha, did not matter.

For me it was also significant that we had had no other professors in our family.

My father was a public accountant, not a CPA. I suspect he did not pass the test. Or didn’t want to try. He often told me that what he had really wanted to be—please keep Cousin Bernie in mind here—was a college history professor. But there was no money for a graduate degree. His assets as a civil servant were already over-pledged. And, perhaps more significant, he heard no encouragement from family, friends or teachers.

As for the rest of the family: My mother was a housewife, as were her sisters. Her sister-in-law was a notable exception. Aunt Sarah was the executive secretary to the head of a large linen company. She was also the only childless aunt, which was viewed as the secret to her success. My uncles would have loved to be Jay Gatsby. But they weren’t. For a bit, Sarah’s husband, Uncle Sammy had the most interesting job. He sold girls’ dresses, frilly ones. He gave me the samples he said no one would miss. Maybe he shouldn’t have done this. After a while the samples stopped and Sammy moved on to sell something else with no more luck. My mother said he spent too much time at Aqueduct Racetrack. Had I known what spending the day at a racetrack entailed I might have found Uncle Sammy as interesting as Cousin Bernie.

Behind thick glasses, Cousin Bernie, carried a trace of mystery. I could sense it but my mother continued to deflect my questions with directions to China, homework or silence. The first clue was revealed on one of Bernie’s trips back to Brooklyn.

I overheard my mother ask: “So, this time, Bernie, are you actually going to visit your mother?” Her voice was calm but tinged with a scolding.

This was strange. Did she mean Bernie’s mother’s gravesite? I did not know where she was buried and had never cared. She was a dead woman I had never met. The voices in the living room, voices I could hear from the kitchen, became more intense.

“I can’t visit her again,” Cousin Bernie said. “She screamed when she saw me. Gertie visits her. That is enough.” Gertie was Bernie’s sister, his only sibling. Like us she lived in Brooklyn.

Holy cow, I said to myself. Holy shit, would have been more to the point. But I had not yet progressed to cursing.

I had no patience to wait to get to the bottom of this story. I marched into the living room. My mother and Bernie looked at me, startled.

I came right out with it: “I thought you said Cousin Bernie’s mother was dead?”

Bernie looked at my mother. My mother looked at Bernie. Bernie nodded.

“Barbara,” my mother said, “Bernie’s mother is a very sick woman.”

“Then how come she’s not dead yet?” I asked. I saw Bernie grin through his sadness.

“Yes, she is sick,” my mother said. “But in the head.”

“So where is she,” I asked.

“In a mental institution,” my mother replied, with a look on her face I recognized. It meant I had exceeded my quota of questions.

I persisted. “You’ve never said her name,” I noted. “What is her name?”

My mother sighed. “Ida,” she said. “Ida Fischkin.

“What?” I cried out.

This was getting weirder. My dead-not-dead aunt, my father’s sister, had the same name as my mother. I hoped this was what the comedians on television called a “coinkydink.”

Over the years I would learn more about Bernie’s mother, whom nobody ever called by her name, as if she had ceased to exist. I was grateful. One Ida in the family was enough. My aunt died, for real, in the 1980s and I did not think much about her until about a decade later. I was a mother by then and my elder son, at three and a half, had stopped speaking. He was diagnosed with Childhood Disintegrative Disorder, a serious and irreversible disability on the autism spectrum. I called Cousin Bernie, by then a well-respected and beloved professor of Psychology (interesting choice) and Mathematics at University College at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, inelegantly known as IUPUI. Cousin Bernie told me that his mother had “full-blown schizophrenia,” and that her symptoms were nothing like those of my son.

I did not tell Bernie that I had doubts about his mother’s diagnosis. My father had once mentioned to me that his sister was a staunch union organizer. He said she would often gather her International Ladies Garment Workers Union banner and go to marches. My father once said he wondered if his sister had been “put away,” because she was causing too much trouble. I have come to understand this was not true. My father added that after their mother’s commitment, Bernie and Gertie had a dreadful childhood. Their father, Louis Moskowitz, a house painter, sent them to live with his mother, a harsh woman who made them follow Orthodox Jewish rules, to which they were unaccustomed. “I always urged Bernie to get out of here,” my father told me. “Told him to go far away. To make something of his life. Not to follow in his father’s footsteps. He was a very smart kid. I told him he could be a professor, as I had wanted to be.”

When Cousin Bernie’s mother died, she was buried after a graveside cemetery in a Long Island cemetery, not far from where I was working as a reporter for Newsday. My father called me at work. “Bernie just flew in,” he said. “Your mother is coming. Can you come?” I could and I did.

The first glimpse I had of my Aunt Ida— a woman who, if mentally healthy, might have risen to be someone important in the labor movement—was in an open casket. According to Jewish law, relatives must identify the dead before they are buried. By then Aunt Ida had a thick old-woman’s beard. Not that it mattered. For her there was nowhere to show her face, outside of institutions. At the cemetery, my father held on to Bernie, stood over the casket and spoke these words. “Dear sister Ida, you have had a horrible life. I am sorry I did not do more for you.”

Cousin Bernie’s own sister Gertie was at the cemetery, too, as was her shy husband Arnie Ralph. Gertie was a large woman, larger than her brother. Her heart was even larger. She had a slight speech impediment and self-esteem that ranged from heartbreaking to inspiring. In one of those heartbreaking moments, she once told my mother that she could not come to a family event because she was ashamed that she had recently gained a lot of weight. She would show up again when she was thinner.

A few days after Aunt Ida’s funeral, I sat at my desk at Newsday and tried to work this story as a reporter. I wanted to find out more about my aunt. I called the communications director for the nearby Kings Park Psychiatric Center. He told me he was not permitted to give me any information but he would, anyway. He phoned back and told me that my Aunt Ida had been at Kings Park for years, less than a half an hour from where I sat in Melville. Then she was moved to Hudson Valley Psychiatric Center, reasons unknown. In total, she had spent 50 years institutionalized. And, yes, schizophrenia was the diagnosis. He said he had no more to tell me. Or perhaps he felt he had already told me too much.

Years after Aunt Ida died I visited Gertie and Arnie in their modest apartment. When Arnie stepped outside for a while, Gertie told me Arnie’s mother had warned her not to marry him because he was “stupid and retarded.” She told me she ignored this advice and gave her future mother-in-law a hearty tongue-lashing. She held her ground. She said Arnie was neither stupid nor “retarded,” but rather a kind and simple man who understood a great deal. For many years he worked cleaning up and doing other tasks for the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. Bernie died in 2001. Gertie a number of years earlier and then Arnie. I went to visit Gertie on her deathbed. Her diabetes and other ailments had finally gotten the best of her, Her last words to me: “Barbara, I never thought I would be this sick.” It occurred to me that “denial,” was the way Gertie had made it through her tough life.

And now some introductory words on a topic which could be a book in itself: The love-life of Cousin Bernie Moskowitz a.k.a. Professor B. B. Morris. (In his obituary he was also identified as Barnett B. Morris).

I was already in high school when the phone rang at Avenue I. Again, it was Bernie. He only wanted to talk to my father. There were no speaker phones in those days. I got on the upstairs extension. I remember every word Cousin Bernie spoke.

“Uncle Dave,” he said, “I have a beautiful woman sitting on my lap.”

Not possible, I thought. It was a lie or a miracle. Then I recalled Bernie did not lie.

“Go on,” my father said.

“Well she is also much younger than I am. And…She has agreed to marry me.”

Silence.

“And…” my father said. He could always sense when there was something else.

“She’s not Jewish,” Bernie said. “I’d like your permission.” My father was not particularly religious but he was very Jewish. For years, he was the president of Congregation B’nai Israel of Midwood, a Modern Orthodox shul across the street from us on Avenue I.

“Bernie,” my father said. “If she is young and beautiful and still wants to marry you I do not care what religion she is. She could be anything.”

Joan Hamilton, Cousin Bernie’s future wife, got on the phone and my father wished her “a lot of luck.” She laughed, as we all did.

Indianapolis sounded a lot less interesting to me than Moorhead Minnesota, Nevertheless, I was thrilled to be invited to the wedding. I was still only a teenager. They could have left me out. I don’t remember the actual wedding. What I do remember is Joan, who is now 85 and whom I often call Joanie. I looked at her in awe, a stunning, sophisticated woman, sitting on Cousin Bernie’s lap, sipping a martini, puffing on a cigarette and surrounded by a bevy of friends and admirers. She worked as a rare book librarian. Man, she was cool. Cool, yet married to Bernie.

I later understood that despite the fanfare and joy, this was a marriage of two troubled people who found one another and learned from one another. They surmounted—and failed to surmount—major challenges that had nothing to do with age or religious differences. And there was no denial. In short, for now, there was plenty of trouble in Indiana’s version of River City.

And yet, Joanie and Bernie had a long, loving, till-death-do-us-part marriage. Cousin Bernie died from congestive heart failure in 2001. Eventually Joanie connected with a new partner. Joanie recently told me to tell it all—with one exception. She was not trying to protect herself but rather to keep others safe. “Basically,” she said. “My life is an open book. Go for it.”

To be continued, next time…