by Mark Harvey

Geography has made us neighbors. History has made us friends. Economics has made us partners, and necessity has made us allies. Those whom God has so joined together, let no man put asunder. —John F. Kennedy addressing the Canadian Parliament, 1961

If you had to design the perfect neighbor to the United States, it would be hard to do better than Canada. Canadians speak the same language, subscribe to the ideals of democracy and human rights, have been good trading partners, and almost always support us on the international stage. Watching our foolish president try to destroy that relationship has been embarrassing and maddening. In case you’ve entirely tuned out the news—and I wouldn’t blame you if you have—Trump has threatened to make Canada the 51st state and took to calling Prime Minister Trudeau, Governor Trudeau.

If you had to design the perfect neighbor to the United States, it would be hard to do better than Canada. Canadians speak the same language, subscribe to the ideals of democracy and human rights, have been good trading partners, and almost always support us on the international stage. Watching our foolish president try to destroy that relationship has been embarrassing and maddening. In case you’ve entirely tuned out the news—and I wouldn’t blame you if you have—Trump has threatened to make Canada the 51st state and took to calling Prime Minister Trudeau, Governor Trudeau.

I’ve always loved Canada. My first visit there was as an eleven-year old when my mother sent me up to Vancouver to live with a friend’s family for the summer. Vancouver is such a jewel of a city and Canadians are such nice people that even at that age I was appreciative of our northern neighbor.

Getting your arms around the Canadian character is not easy. There are a few stereotypes, one of them being that Canadians are polite. Guess what: in general, they are polite. But I have a sense that Canadians have two very different sides to their character, one being the pleasant law-abiding citizen, and the other represented by their raging hockey fans or their certifiably crazy world cup ski racers, once called The Crazy Canucks. To their credit, Canadians keep these two parts of their personalities in separate vaults and usually don’t mix the two. But have no doubt: behind the good manners and friendly dispositions, Canadians have a fierce side and iron will not to be trifled with.

To understand the Canadian psyche, you could start with ski racing. For years, the Europeans—Swiss, Italians, Austrians, and French—dominated the speed events on the world cup circuit. Very few racers outside of those nations ever got on the podium of the big downhill races such as Kitzbühel, Wengen, and Garmisch-Partenkirchen. Then in the late 1970s and extending into the mid 1980s, five Canadian ski racers, Ken Read, Steve Podborski, Dave Irwin, Todd Brooker, and Dave Murray blew the traditional European dominance to bits.

I won’t go into great detail about their scores of wins over the years, but perhaps the most injurious to the European aristocracy was when the Canucks won the most prestigious of all the downhill events, the Hahnenkamm, four straight years. Beginning in 1980 when Ken Read won, followed by two Podborski wins, and culminating with Todd Brooker’s win in 1983, the Canadians did it their way. They were all superb athletes, but they won the moniker of Crazy Canucks by taking horrendous risks on their lines at 85 mph. It was a glorious thing to watch and sent Austria into a few years of clinical depression.

I was a ski racer myself and raced against these guys a few times, though nowhere near at their level. I rode the chairlift with Read and Brooker at some event and if you didn’t have clear evidence of their prowess on the slopes, you’d never guess they were Austrian-slayers. They had none of the arrogance that often accompanies world-class athletes. Both were boyishly enthusiastic and, here we go, polite. I was too in awe of being in the presence of my heroes to remember much of the conversations.

Trump has managed to rattle the Canadians with his infantile threats of making Canada the 51st state. He’s good at getting under people’s skin, even those with studied forbearance. Even the leader of the Conservative Party, Pierre Poilievre, sometimes called Trump-lite for his populist instincts and emphasis on smaller government, got riled by Trump’s jabs and made a defiant speech about how Canada will never succumb to the United States. Justin Trudeau and various premieres have made similar speeches.

There’s an intensity to their broadsides, where you can see the fierce part of their character—the ferocity seen on hockey rinks and ski slopes— bleeding into their disciplined civility. If nothing else, Trump has stirred up Canadian patriotism and while Canadians are less likely to drive around in big pickup trucks waving a flag, there’s no doubt of the strong allegiance to the Maple Leaf, or l’Unifolié as it’s called in Quebec.

After watching one premiere make a speech on YouTube vowing not to become a 51st state, an unbidden thought popped into my head: I wonder if Canada can help us negotiate the vandalism being wrought on the United States by Donald Trump and Elon Musk. It was a funny thought because militarily I’ve always thought of the United States as being Canada’s protector if they were ever truly attacked. And God knows we have the military. But in a time when any decent values of the United States are being mortally challenged, I wonder if our truly decent neighbor to the north can help guide us back to some semblance of democracy.

Years ago, I had the good fortune to float the Tatshenshini River with a small group of people including Pierre Trudeau and Justin Trudeau, who was still a teenager at the time. The night before the trip, we circled up as a group and went around the room introducing ourselves and saying a little about our background. One American woman babbled on for several minutes about all her accomplishments in the world of conservation. It was a lengthy list of near everything she’d done and quite tiresome. Pierre Trudeau was next. He said, “My name is Pierre Trudeau and I used to be a Canadian politician.” That was it. His brevity next to the American woman’s jabbering was celebrated around the room by a dozen quiet smiles and secret glances.

I know that Pierre Trudeau was a controversial prime minister and even a firebrand, but in person on that river trip, he was as kind and unassuming as a person could be. There was none of the almighty affectation that a leader of a great country might assume.

I haven’t read too many Canadian authors, but I have read some works of Robertson Davies, Alistair Macleod, and Margaret Atwood. Different writers all, but I’d say one commonality is their precision with language and their economy with words. Davies is perhaps the most ornate of the three, but none of them swim around in a shamble of pell-mell prose. When I think of their writing, I think of carefully built dories or sailboats: every word used efficiently to move the story along and move the reader.

MacLeod was most famous for his short stories (he only wrote one novel) and if you haven’t read his work, you might want to start with The Boat. It’s an achingly melancholic story of a fisherman’s family in Nova Scotia told from the point of view of a man looking back on his childhood. The story is filled with tension between the husband and the wife, traditional seafaring and a creeping modernity, and sacrificing personal dreams to provide for a family.

In one passage describing the conflict between the son pursuing his studies or following in his father’s footsteps and going to sea, Macleod writes,

And I knew then that I could never leave him alone to suffer the iron-tipped harpoons which my mother would forever hurl into his soul because he was a failure as a husband and a father who had retained none of his own. And I felt that I had been very small in a little secret place within me and that even the completion of high school was for me a silly shallow selfish dream.

Macleod’s stories are built out of the land and sea, farms, fishing villages, and mines. His characters suffer the cold briny winds in wooden boats, the coal mines, and the heartbreak of lost traditions. The few other Canadian authors I’ve read tell stories of introspection, isolation, and interior conflict, often with a vast natural landscape filling in for what a character can’t or won’t say. Sometimes the writing is restrained but overwhelming in its emotional force. Iron-tipped harpoons and freezing squalls.

In my travels through Canada, I’ve stopped at a few art museums in Toronto and Vancouver and what I noticed about the featured Canadian artists when I visited was that the central character of their paintings was usually the landscape. Even when humans were featured, they were dominated by vast forests, rivers and mountains.

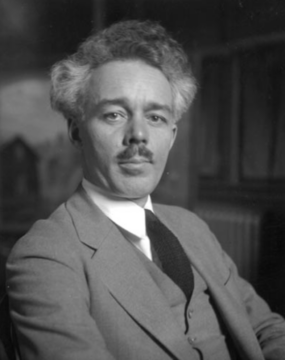

It was only later that I learned about The Group of Seven—seven Canadian painters most prominent in the 1920s who focused on landscapes. The leader of the Group of Seven was Lawrence Harris, who came from the tractor fortune, Massey-Harris (later to become Massey-Ferguson). Harris helped finance the painters and they traveled as a group around Canada to sketch and paint landscapes. Their efforts were considered to be the first major Canadian art movement.

Each of the seven painters had a distinctive approach, but the landscapes I’ve seen were painted in a lush, impressionistic style. Looking at the work of the seven artists (and the ones subsequently influenced by the movement) I get the sense that the land spoke to them and reached the depths of their souls. The mountains, icebergs, lakes and trees portrayed fairly quiver and bend with emotion.

I’m not sure what defines a culture but I have to believe that so few people living in such a vast and rugged landscape helps define Canadians. In an ever more crowded world, it’s boreal reaches are a still wild land.

A few years ago, I took the train from Banff to Vancouver, a two-day journey and one of the most spectacular trips I’ve ever done. The stewards were a young energetic lot that didn’t let up with parlor games, stories about scenery we had passed, serving us copious amounts of food and pouring booze by the liter. One of the games was to write a poem about the train trip. They gave us 20 minutes and I wrote the following, which I am disproportionately proud of.

If you cross Canada on the rails

Over hill and over dales

O the scenery your trip entails

Ev’n Swiss alps by comparison pales

Have your fork and grab your cup

Drink hard you will, bottoms up

Food aplenty, and wine a’pourin’

Charming stewards, never borin’

O Canada, your land us did smitten

Not even captured by poems here written

Entertaining despite 20 hours sittin’

From Banff west to the mighty Pacific

The pioneers, your forebears, most prolific

Every mile a brand-new story

Of buildings, bridges, all things of glory

In the morning, mountains shear

At midday, the skies are clear

Afternoons of endless river

All this booze, o my liver

Tell your ma, this trip would behoove ‘er

Thick pines outside, next stop Vancouver

As our train nears its destination

We marvel at this earth’s creation

From a loud neighbor to the south

And despite this poor poetry, o my mouth

I say to my Canadian brethren–and this may not rhyme

Your train, your land is most sublime

The stewards gave me a beautiful silver salmon pin for my poem. When I showed it to my girlfriend with overweening pride, she said, “I think they gave that pin to all the children.”

Like many Americans, I feel a deep embarrassment and regret for how Trump has insulted our great northern neighbor. It’s the sort of thing one might feel after a drunk relative has trashed someone’s house and gravely insulted its owner. All we can hope is that a people known for their forbearance can forgive us sometime down the road.