by Barbara Fischkin

Moving forward, I plan to use this space to experiment with chapters of a memoir. Please join me on this journey. Another potential title: “Barbara in Free-Range.” I realize this might be stepping on the toes of Lenore Skenazy, the celebrated former New York News columnist, although I don’t think she’d mind. Lenore was also born a Fishkin, albeit without a “c” but close enough. We share a birthday and the same sensibilities about childhood. These days Lenore uses the phrase “free-range,” typically applied to eggs, to fight for the rights of children to explore on their own as opposed to being over-supervised and scheduled.

I feel free-range, myself. I don’t like rules, particularly the unnecessary and ridiculous ones. My friend Dena Bunis, who recently died suddenly and too soon, once got a ticket for jaywalking on a traffic-free bucolic street in Orange County, California. She never got a jaywalking ticket in other far more congested places like New York City and Washington, D.C.

As a kid, I was often free-range, thanks to my parents, old timers blessed with substantial optimism. I have been a free-range adult. I was a relatively well-behaved teen but did not become a schoolteacher as recommended as a good job for a future wife and mother. I wanted a riskier existence as a newspaper reporter. I did not marry the doctor or lawyer envisioned as the perfect husband for me by ancillary relatives and a couple of rabbis. Instead, I married Jim Mulvaney, now my Irish Catholic spouse of almost forty years, because I knew he would lead, join or follow me into adventures.

I left newspapering as my career was blooming to write books, none of which made me a literary icon or even a little famous. I am glad I wrote them.

As for my children, I raised them by consulting my gut, my parents’ example—“they’ll be okay”—and my intellect. Not Parenting magazine.

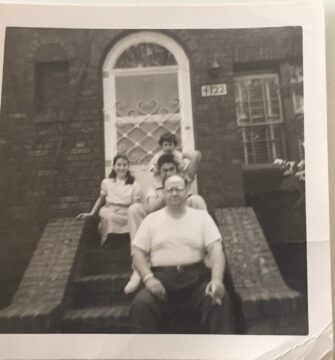

I write this as spring approaches. Spring brings out memories. It inspire writers to write memoirs. My first recollection of spring is smelling it when I walked home from Public School 203 in Brooklyn, New York. Eight years old and unfettered by a parent. My mother was at home where she would greet me with a hug and a kiss, a glass of milk and a Hostess cupcake. As far as I know, it never occurred to her that as a fourth grader I couldn’t get home on my own. Home was a semi-attached two-story red brick house with a front stoop, a shared driveway, a garage and a back porch and garden. Our home was 4722 Avenue I in the Midwood section of Brooklyn. To get home from school I took a New York City bus from Avenue M down Utica Avenue to the Avenue I stop. For my fare, I flashed a discounted pink bus pass. Lots of kids did this, including my best friend who got off at Avenue J, the stop before mine, as we made plans to see each other later or the next day.

One spring afternoon I crossed Utica Avenue—maybe with the light, maybe running against it. I walked past a commercial section into the residential area and was hit with a new, beautiful smell. Spring. That aroma had been there every spring of my young life. But I remember the day when I first understood how the smell registered with the season and within my soul. I felt as if I had discovered this smell on my own, like the explorers I learned about in school. This was the beauty of being a fourth grader and walking home from the bus, alone.

Now, when I dig deep into my memory and recreate that smell, I know that it was a mixture of lavender and berries, or more specifically the fragrance of newly blooming lilacs. That there were lilacs on Avenue I and in its vicinity does not surprise me. For a historical novel I am now deep into writing, I have researched the flora of Eastern Europe and learned that lilacs grew there in abundance, on bushes and on trees. There were many former Eastern European refugees—and many children of those refugees—in Midwood.

Lilacs grew throughout the Ukrainian shtetl where my mother was born and flowed into the surrounding countryside. My mother’s sister, Aunt Doris, once told me she also remembered sunflowers, which today we recognize as an emblematic symbol of Ukraine, that mighty country—war-torn yet again. If there were any sunflowers on Avenue I, I missed them. My strongest floral memory is of lilacs, particularly on bushes. They are smaller than sunflowers in stature, perhaps easier to grow.

I like to think that the smell of lilacs brought back good memories for those former Eastern European refugees who, like my mother, had escaped a violent twentieth century outbreak of anti-Semitism. I like to think these former refugees told their children about lilacs. It was my impression that most were like my mother who left Ukraine as a child, herself, after a 1919 pogrom. They spoke unaccented English and fast, clipped Yiddish. There were a few others, though, who carried heavy accents and, as I learned at an early age, the horrors of the Holocaust. A local tailor whose shop was on Avenue J, had Auschwitz prisoner numbers tattooed on his arm. As a child, I often stared at the numbers when my mother sent me to pick up dry cleaning. The tailor saw me stare and said nothing. I’d like to think he felt it might be better for my parents to explain. I asked my mother about the numbers on the tailor’s arm and she said he had not removed them because he needed to remind people about hatred and how humans survived hatred. It was a lot for a little girl to hear. But her words stuck with me.

——-

It is impossible for me to start a memoir anywhere else but on Avenue I. My parents and grandparents bought that house for $4,000 with an $800 down payment in 1939. My grandparents died in that house and my parents lived there until their own deaths in 1987. My earliest memories all take place on Avenue I. These memories are built from an understanding of both history and the value of community. Children who live within a community—although not one with random or ridiculous rules—have more leeway to range free. Everyone knows them.

There is one Avenue I photograph of myself and my older cousin Shelli, which I look at often. It was taken inside Congregation B’nai Israel of Midwood, a synagogue my grandparents helped to build. “The shul,” as we called it, stood diagonally across the street from our house and was still there when I last visited in 2021. In the photograph I am not quite two years old, yet I remember the day it was taken. It was the Saturday of the bar mitzvah of my older brother, Ted, or Teddy, as he was then known. He was 12 years older and my only sibling. The religious part of the bar mitzvah, when Teddy read his Haftorah, his assigned portion of the Torah, took place that morning at the shul, with many neighbors in attendance. The photograph was taken that evening at a reception, also at the shul, after sunset when Shabbos was over. Murray Levenstein, a well known Brooklyn kosher caterer, supplied the food. In the photo I am marching into the reception, holding hands with Shelli, who was my first babysitter. Shelli was all dolled up in a chiffon dress with puffy white sleeves and a skirt embroidered with pink flowers, not lilacs but beautiful all the same. I am in a white toddler dressy-dress. We are holding hands. This is what I remember best: Holding Shelli’s hand and stopping to have our picture taken.

Not long after I turned two something much sadder happened on Avenue I, inside of our house.

Each morning my mother would send me upstairs to my widowed grandmother’s bedroom with a small plate that held an orange cut into quarters. The orange was for my grandmother to eat either before or after she injected herself with insulin for her diabetes. I remember watching the injection and her eating of the oranges. Sometimes, she offered a bite.

One morning, from upstairs I called down: “Mommy, grandma won’t wake up.” I will never forget my mother’s reply: “Give her a shake,” she said. I did. “Mommy,” I called down. “I shook her. Grandma won’t wake up.”

My mother ran upstairs, looked at her own mother and screamed “Mama.” She screamed “Mama,” again and again, louder each time. Almost immediately the house filled with our women neighbors. It was a weekday morning. They left their breakfast dishes in the sink and came to help. The men were at work.

The women keened. I was scared. Eunice Lazarus, our next-door neighbor, on the corner house attached to ours, scooted me outside. The next thing I remember is being with her in the bedroom she shared with her husband, who I knew only as Dr. Lazarus. He was the neighborhood dentist, with an office in his house. I remember Mrs. Lazarus teaching me that very morning how to make a bed. A perfect distraction. She let me hold a section of a sheet all by myself.

By the time I was 4, I had been inside almost every house on our side of Avenue I, one block that ran from East 48th Street to Schenectady Avenue. I can still tell you something about everyone who lived on Avenue I during my childhood years. As this memoir expands I hope to tell more. For now, I’ll stick to the good. Certainly there were a few arguments, a few mean things said. I remember a few directed at me, a few I shouted out as a snotty little girl. Just some normal, everyday arguments. No long grudges, as far as I know.

The block lineup began with the Lazaruses, next we Fischkin then the Weiners. The Weiners were older, Orthodox people. From a distance they seemed gruff. But one weekend when my parents went away, I stayed overnight with Mr. and Mrs. Weiner. I was invited to sit in Mr. Weiner’s comfortable television chair and to watch whatever program I chose. The Weiners watched with me, Mr. Weiner from a stiff dining room chair.

Next were the Friedmans. Al Friedman taught me to ride a two-wheel bicycle, after my father’s patience with my klutziness dwindled. Mrs. Friedman always invited me in to chat with her and her parakeet. Next door was Mrs. Fenichel, a schoolteacher who became one for all the right reasons. In her basement, she allowed me to help build a miniature model city for her students. It was Mrs. Fenichel who talked my worried mother into letting me skip third grade with my closest pals.

Mrs. Haut lived next door to Mrs. Fenichel. She once took me on an expedition. She drove me miles away from Brooklyn to my first shopping mall—Green Acres on Long Island. She had heard me whining to my mother that I was the only one in my class who did not have a stylish mohair sweater. Mrs. Haut made sure I came home from the mall with a white one. Mr. Haut was an affable kosher butcher who often brought home orders for the neighborhood. I can’t remember the exact name of the people who lived next door to the Hauts. The Yosanas? They kept to themselves and I don’t think I ever went inside. Maybe they were shy . I think of the last two houses on the block as my “babysitter” houses. I babysat the Levines’ grandson, a good-looking kid whose name I do not remember. The Bergs lived on the corner and their daughter babysat for me. I still find the Bergs’ son on Facebook.

In those years everyone on our side of Avenue I was Jewish, although only the Weiners were religious. The complete Jewishness changed when the Espositos moved in, although the sense of community stayed the same for years. When Mr. Esposito died—I was grown by then—my father Dave, the perennial president of Congregation B’nai Israel of Midwood, went to church to get a Mass card and pray for his neighbor’s soul. Around the same time, there was a generally successful attempt to redline the neighborhood and scare white people into selling cheap. Realtors warned that black people were moving in. My parents did not move but many other people did. Now, when I drive by the old neighborhood I imagine the African and Afro-Caribbean Americans who live there, building their own sense of community. I can’t imagine it any other way. The need to do this comes from the sidewalks and the flowers of the neighborhood. If it is any other way, I do not want to know.

——–

Some memoir background: My childhood happened on Avenue I. My history, as far back as I can trace it, starts in what eventually became part of western Ukraine, in that shtetl of my mother’s, which was once called Felshtin. Now, as I approach my seventieth birthday my thoughts bounce back and forth between the Felshtin of my heritage and the Avenue I of my childhood. I was once asked to write a memoir. I was in my early forties and thought this was silly. I had not lived enough. But movie people wanted this memoir—what they actually wanted was a wife writing a memoir about living with a real-life character of a husband. The movie people tantalized me. Write the book and we will make it into a film, they said. My brother loved the idea and suggested Sandra Bullock play me, even though he had absolutely no way to contact her. Okay, I said, thinking this was dumb. “I will write a memoir. But I will make up some of it.” Their reply: “No big deal. Who says a memoir has to be true?” I had spent years as a journalist. “Okay,” I replied. “But if this is going to be a partially made-up memoir, I am going to call it a novel, as in fiction.” The movie people loved this idea. They deployed a literary agent who got me a deal for not one made-up memoir but two—and an advance I could not refuse. The movie never got made. The books were well reviewed but not well purchased. Yet people still read them and tell me they are very funny. One reader recently anointed me a “comic genius,” a hyperbole I cherish. The books were also misunderstood, mostly by relatives apart from my brother, who were confused about the confluence of fact and fiction. Today this is called “auto-fiction.” Then there was no name for it, which also made it a hard sell.

Now, though, I feel old enough to begin to write a real memoir. To try to remember with as much accuracy as I can. And to make this memoir not merely a piece of family history but a book that reminds readers about the freedom children once had. For those who say the times were different then, I reply that there is some truth to this. But Midwood was not without danger or fear. There were nightime house burglaries and gamblers in the “candy store” on Avenue J. There were boys who seemed to belong to gangs or the era’s moral equivalent. There were also people in the neighborhood who had survived far worse dangers. The tailor, for one. To those neighbors, Midwood looked like heaven on earth. So, can free-range be replicated today? In some form, I think it can. I urge you to look at what Lenore Skenazy has to say about this. She says it better than I can. There is also a new book that urges parents to take away their children’s phones and give them more freedom to play. Some find this book too extreme. I wonder if a middle ground might be useful. We have gone too far into the depths of helicopter-ing and screen time. We need to try to crawl out a bit. Slowly, perhaps. Or as my mother often said when chatting with her friends on Avenue I: “Everything in moderation.

Endnote: Please see Michael Dobie’s recent column in Newday, which also inspired me to write this. It begins with the words: “When we were kids, it seemed like we were always outdoors.” Here’s to the outdoors. Here’s to spring.