by Herbert Harris

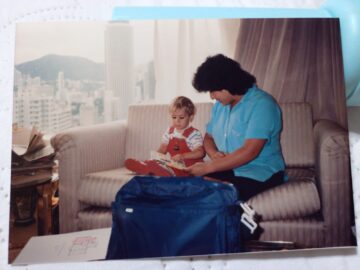

The greatest privilege of my childhood was growing up in a house where books had their own room.

My father’s library occupied the second floor, the only room without a window air-conditioning unit. On summer afternoons in Washington, DC, when the heat and humidity pressed down like a weight, the rest of the house hummed and rattled with machines straining to keep up. The air in the library stayed stubbornly still. It was the early 1970s, and I was on summer break after tenth grade, retreating there to find the peculiar solitude this room alone offered. Each book I opened sent up a cloud of dust that glittered in the angled sunlight. Shutting the door turned the room into a sauna, but in that quiet stillness, I didn’t mind. It felt like the price of admission to a different world.

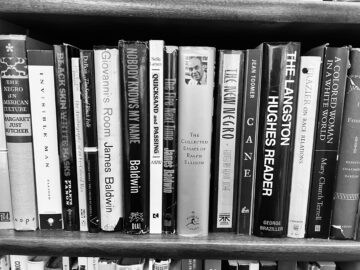

The previous summer had unfolded differently. I had just finished ninth grade, where we surveyed the classics of English literature and retraced the decisive moments of Western civilization, reliving the deeds of its great men and women. I spent long afternoons in the library, sinking into those books as the heat pooled around me. I melted into a reclining chair and wandered through the past. That immersion had felt complete, even sufficient. But this summer, I arrived with a different appetite. I was growing skeptical of the Eurocentric narratives threaded through everything I was learning. I sensed there were other stories and vantage points, and I came looking for them.

I picked up the book I had been reading a few days earlier and turned to the page marked with an index card. I searched for the sentence I remembered, but at first the words slipped past me. James Baldwin was writing about a Swiss village, about children shouting “Neger” as he walked through the snow. Seeing the word on the page registered instantly, not as surprise but as recognition. I had learned early what it meant to be called that name in its American form. That knowledge had settled into my body long before I could articulate it. Read more »

This is the first in a series of three articles on literature consider as affective technology, affective because it can transform how we feel, technology because it is an art (tekhnē) and, as such, has a logos. In this first article I present the problem, followed by some informal examples, a poem by Coleridge, a passage from Tom Sawyer that echoes passages from my childhood, and some informal comments about underlying mechanism. In the second article I’ll take a close look at a famous Shakespeare sonnet (129) in terms of a model of the reticular activity system first advanced by Warren McCulloch. I’ll take up the problem of coherence of oneself in the third article.

This is the first in a series of three articles on literature consider as affective technology, affective because it can transform how we feel, technology because it is an art (tekhnē) and, as such, has a logos. In this first article I present the problem, followed by some informal examples, a poem by Coleridge, a passage from Tom Sawyer that echoes passages from my childhood, and some informal comments about underlying mechanism. In the second article I’ll take a close look at a famous Shakespeare sonnet (129) in terms of a model of the reticular activity system first advanced by Warren McCulloch. I’ll take up the problem of coherence of oneself in the third article.

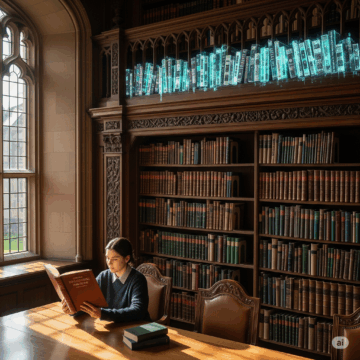

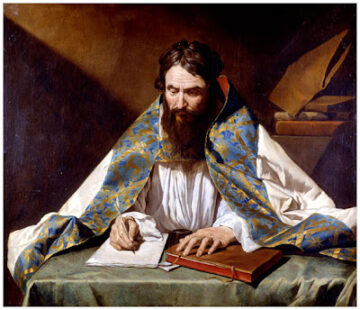

As an émigré from the dusty, sun-scorched Carthaginian provinces, there are innumerable sites and experiences in Milan that could have impressed themselves upon the young Augustine – the regal marble columned facade of the Colone di San Lorenzo or the handsome red-brick of the Basilica of San Simpliciano – yet in Confessions, the fourth-century theologian makes much of an unlikely moment in which he witnesses his mentor Ambrose reading silently, without moving his lips. Author of Confessions and City of God, father of the doctrines of predestination and original sin, and arguably the second most important figure in Latin Christianity after Christ himself, Augustine nonetheless was flummoxed by what was apparently an impressive act. “When Ambrose read, his eyes ran over the columns of writing and his heart searched out for meaning, but his voice and his tongue were at rest,” remembered Augustine. “I have seen him reading silently, never in fact otherwise.”

As an émigré from the dusty, sun-scorched Carthaginian provinces, there are innumerable sites and experiences in Milan that could have impressed themselves upon the young Augustine – the regal marble columned facade of the Colone di San Lorenzo or the handsome red-brick of the Basilica of San Simpliciano – yet in Confessions, the fourth-century theologian makes much of an unlikely moment in which he witnesses his mentor Ambrose reading silently, without moving his lips. Author of Confessions and City of God, father of the doctrines of predestination and original sin, and arguably the second most important figure in Latin Christianity after Christ himself, Augustine nonetheless was flummoxed by what was apparently an impressive act. “When Ambrose read, his eyes ran over the columns of writing and his heart searched out for meaning, but his voice and his tongue were at rest,” remembered Augustine. “I have seen him reading silently, never in fact otherwise.” About a third of the way through a first-year humanities honors course, one of my more engaged and talkative students pulled me aside after class for a private chat. She waited, clearly anxious, while the rest of her classmates filed out and then turned to me with her eyes already filling up with tears.

About a third of the way through a first-year humanities honors course, one of my more engaged and talkative students pulled me aside after class for a private chat. She waited, clearly anxious, while the rest of her classmates filed out and then turned to me with her eyes already filling up with tears.

Last night I (Danielle Spencer) went to the New York Film Festival screening of Memoria (dir. Apichatpong Weerasethakul) in Alice Tully hall at Lincoln Center. I last joined a large gathering 19 months ago, in March of 2020.

Last night I (Danielle Spencer) went to the New York Film Festival screening of Memoria (dir. Apichatpong Weerasethakul) in Alice Tully hall at Lincoln Center. I last joined a large gathering 19 months ago, in March of 2020.

Irish-Canadian author

Irish-Canadian author