MORE LOOPY LOONIES BY ANDREA SCRIMA

For the past ten years, Andrea Scrima has been working on a group of drawings entitled LOOPY LOONIES. The result is a visual vocabulary of splats, speech bubbles, animated letters, and other anthropomorphized figures that take contemporary comic and cartoon images and the violence imbedded in them as their point of departure. Against the backdrop of world political events of the past several years—war, pandemic, the ever-widening divisions in society—the drawings spell out words such as NO (an expression of dissent), EWWW (an expression of disgust), OWWW (an expression of pain), or EEEK (an expression of fear). The morally critical aspects of Scrima’s literary work take a new turn in her art and vice versa: a loss of words is countered first with visual and then with linguistic means. Out of this encounter, a series of texts ensue that explore topics such as the abuse of language, the difference between compassion and empathy, and the nature of moral contempt and disgust.

Part I of this project can be seen and read HERE

Part II of this project can be seen and read HERE

Images from the exhibition LOOPY LOONIES at Kunsthaus Graz, Austria, can be seen HERE

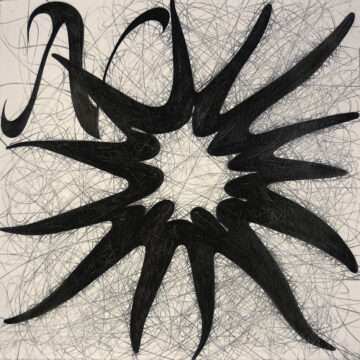

7. EEEK

Michel de Montaigne’s famous statement—“The thing I fear most is fear”—remains, nearly five hundred years later, thoroughly modern. We think of fear as an illusion, a mental trap of some kind, and believe that conquering it is essential to our personal well-being. Yet in evolutionary terms, fear is an instinctive response grounded in empirical observation and experience. Like pain, its function is self-preservation: it alerts us to the threat of very real dangers, whether immediate or imminent.

Fear can also be experienced as an indistinct existential malaise, deriving from the knowledge that misfortune inevitably happens, that we will one day die, and that prior to our death we may enter a state so weak and vulnerable that we can no longer ward off pain and misery. We think of this more generalized fear as anxiety: we can’t shake the sense that bad things—the vagueness of which render them all the more frightening—are about to befall us. The world is an inherently insecure and precarious place; according to Thomas Hobbes, “there is no such thing as perpetual Tranquillity of mind, while we live here; because life it selfe is but Motion, and can never be without Desire, nor without Fear” (Leviathan, VI). Day by day, we are confronted with circumstances that justify a response involving some degree of entirely realistic and reasonable dread and apprehension, yet anxiety is classified as a psychological disorder requiring professional therapeutic treatment.

Because fear can paralyze us, it is an effective political tool, instrumentalized to ensure that one group retains its power at the expense of another. It lurks quietly in the divide between the two; its invisibility makes it all the more effective. The powerless are left to imagine what harm can come to them, and often, in the hopes of obtaining security and protection, will submit to their own repression, rendering overt coercion unnecessary. As Alexis de Tocqueville observed: “not only will they let their freedom be taken from them, but often they actually hand it over themselves.”

Far more specific than fear and anxiety is terror—which is defined by its randomness and arbitrariness. Terrified, we invoke vivid images in our mind’s eye as we anticipate the terrible things that can happen to us. Yet while the powerful seek to hide it, they are also afraid; shielded from the more immediate threats to their person or property, they are terrified of what their privilege can neither protect them from nor prevent. Paradoxically, they feel more fear than those accustomed to far less safety—including the fear that the powerless will one day rise up and depose them.

8. HOPE

When we say that things will somehow work out and that we possess the necessary resources to face whatever comes our way, we sometimes tack on the word “hopefully.” We believe we can cope with what life throws at us, but invoke hope as a measure of caution or superstition. We do not like to be too presumptuous: lest we give in to the dangerous illusion that we are ever fully in control, we say, eyes gazing upwards, “hopefully;” “God willing.”

On a secular level, hope is linked to our ability to project past experience onto the future; it understands that things change, that no set of circumstances stays the same for long, and that our actions can and do influence the outcome of events. Even pessimists quietly hope for the best, harbor the secret belief that things might unexpectedly improve. Situated on a continuum with wishful thinking at one end and unfounded expectation at the other, hope is a positive attitude directed at an unknown future. We gaze upwards in anticipation, a vestige, for some, of the benevolent parent bending over the bed or crib, whose care and attention once taught us to trust.

Courageous people who fight against all odds do so because they trust; their hope for improvement is based on experience. The knowledge that their action inevitably changes a given outcome is a prerequisite of their agency; it gives them the strength to lay the ground for creating a new reality. Hope belongs to the courageous, yet it also makes us vulnerable, strips us down to our naked humanity. This is why it is used as a method of torture: prisoners are led to believe in their imminent release or some impending amelioration of the harsh treatment they’ve been subjected to, only to have these promises cruelly withdrawn at the last moment. They are taught that hope can be dangerous, and unless they find a place to hide their hope and keep it safe, they eventually lose it.

We are mortal beings in time; even in less extreme circumstances, we despair when our hopes fail to materialize. We’re made to feel silly or naïve for indulging in hope, or we fear we’ve betrayed our better judgment, given in to foolishness. We lose belief in our abilities, the very thing necessary to bring about change. Yet it’s not despair that is the opposite of hope, but rather dread: the state of mind in which one is paralyzed, unable to shake the sense of bad things coming. And so we struggle to maintain the conviction that good things can prevail or are at least possible—because even if we know that hope is based, in part, on illusion, and that the world is not necessarily made up of largely benevolent forces, we also know that we need to believe in this illusion to survive.

9. SLEEPWALKING

The child, pillow in hand, slips out of bed and unlatches the door to the outside. In a state of deep sleep, it will curl up somewhere in a corner and only wake up the next morning, with no memory of its nocturnal wanderings. Modern psychology views sleepwalking in children as a symptom of trauma or abuse; Sigmund Freud postulated that the adult sleepwalker is trying to find his or her way back home, to the original bed of childhood. But how much of his theory applies when we diagnose an entire society as somnambulant: are we searching for the innocence we have lost—or are we sleepwalking toward our own demise?

Like Lady Macbeth, whose troubled conscience despaired over her crimes and the ineradicable odor of blood on her hands and who finally confessed to murder while sleepwalking, it appears that certain realities can only be experienced in a fugue state. For we, too, have blood on our hands; we find ways to rationalize our culpability in a political order that has done and continues to do extraordinary violence, but our reasoning doesn’t hold and we are never fully convinced of our blamelessness. “Out, damned spot!” we cry when our psyche can no longer bear the stain of its own contradictions. Even when power protects us and we need not fear being called to account, guilt seeks its inevitable outlet.

Yet some are immune; they have managed to suspend their conscience in the name of some higher cause. To inflict pain with impunity and feel no remorse in doing so requires a logic in which the meanings of things have become inverted. The victim is presented as aggressor; perpetrators transpose the peril they themselves embody onto those they persecute. On the surface, this seems to work very well: reasoning is turned upside-down, black becomes white, language is drained of all sense, and the assailant believes his or her own version of reality. One remains in the right, and when doubt and common sense threaten to unravel the narrative, fervency gives way to fanaticism.

We are never fully aware of what we do, never fully unaware; our behavior consists in percentages of each. We are nearly, but never entirely awake, nearly, but never entirely asleep. The somnambulist, ignorant of his or her nocturnal confession, offers proof that our crimes eventually gravitate toward retribution. Although we may never experience true remorse, we are nonetheless compelled to betray ourselves in a subconscious drive to seek out the punishment a part of us knows we deserve. As with Lady Macbeth, “unnatural deeds do breed unnatural troubles: infected minds to their deaf pillows will discharge their secrets.”

10. HYPOCRISY

Diplomacy generally calls for compromise; occasionally, a sacrifice of values previously deemed non-negotiable can seem crucial. But where does compromise cross the line to self-betrayal? If we assume that the diplomat’s motive is sincere, a willingness to sacrifice extends to a critical point beyond which compromise amounts to unacceptable capitulation. Yet to achieve its goals, diplomacy necessarily entails a degree of dissimulation. Moral arguments are often presented as a façade behind which another, more pragmatic agenda is at work. If we agree with this agenda, we consider the façade necessary both as a convention and a means of protecting our interests; if we don’t agree, we accuse the offending party of hypocrisy. Collaborating in this façade makes us all, to a degree, complicit; ingenuous or not, we protest when high-minded values are revealed to be no more than a mask, even if we were prepared to accept this mask as long as it suited our purposes.

Hypocrisy can be defined as the incongruence between proclaimed standards of moral virtue and what a person or body of individuals actually does; often based on asymmetrical power, hypocrisy creates a veneer of honor and uprightness to cloak its coercion of a weaker party in moral imperative. We engage in playacting to hide our ulterior motives and to masquerade our own ethical contradictions; we hurl slander to deflect attention from our own bad behavior. Conversely, we use flattery to ingratiate ourselves with people more powerful than ourselves. The curious thing is that we believe our own lies, particularly about our culpability. The child caught stealing will, in a flood of tears, protest its innocence; it cries out in wounded pride, insists it has done nothing wrong, and in the end feels truly outraged, wronged, the victim of false accusation. The child derives its sense of moral rectitude from its own individual needs; being caught in the act of wrongdoing, for instance, pales in significance when compared to what it perceives to be the larger crime of having been unjustly deprived of something it feels it has earned and deserved.

And so hypocrisy automatically delivers its own justification: in an unfair world, a rhetorical performance of a set of moral and ethical values one has no intention of adhering to is regarded as a legitimate means of maintaining the status quo or averting conflict, and as such, is widely practiced. Yet hypocrisy is also, simultaneously, the language of willful amnesia and self-deception. I tell you the story you are capable of believing or are willing to subscribe to on the surface in order to make it easier for you to agree with me. The false pretenses I use to achieve my aims may be internalized; in any case, they retreat to the background, shadowed by the higher goals I feel compelled, as my moral right, to defend by any means necessary.

11. PRIDE

How often do we take stock of our vocabulary? When my interlocutor uses words such as “shame,” or “guilt,” or “pride,” am I sure the words they’re using match my own experience? We assume that we’ve reached a consensus on the meaning of certain terms, but if people associate them with different emotions, there is little recourse for assessing the distance between them.

Pride, it would seem, is the inverse of shame; what sets the two apart from other emotions such as disgust or fear is their conspicuous connection to childhood. Being proud is more than a state of self-esteem. Observe a person bursting with pride: it’s hard not to notice the puffed-out chest, the unspoken “look at me!,” the sudden resemblance to the little boy or girl they once were, basking in the praise of a parent or teacher. Psychology teaches us that our mental and emotional growth are contingent on approval; we cannot exist, cannot realize our potential without the validation of others. Pride, then, is a factor in a social equation and a person’s biography: it requires the mirroring of others. We duck our heads in shame and try to hide, but a proud person wishes to be seen. Just as we rarely feel shame at our little hypocrisies and misdemeanors unless we’ve been caught in the act of committing them, we only truly experience pride when someone is there to applaud us.

For some, however, pride can get along entirely without attention and acclaim; it can simply mean the pleasure we experience at our achievements or the achievements of those we care about. Pride, then, can be a relatively quiet affair to be enjoyed in private. Yet it’s also the word we use to refer to the sense of autonomy or power we feel we are compromising or even relinquishing when we are forced to “swallow our pride” and ask for help. And what about dignity? Are they two distinct entities or merely different facets of the same thing? Dignity would seem to be an inherent trait, a manner of bearing in the world independent of fortune, while pride is dependent on context. We praise those who maintain their dignity in the face of poverty, slander, or persecution; we revere the stoic political prisoner and dissident, but pick at the pose of the proud. Pride comes before a fall, we are told; surely every language offers a similar proverb. It’s as though pride contained the possibility within itself that it is quite likely an exaggeration, a fabrication lacking much of the justification it lays claim to. We grow bored of the proud parent’s pictures and anecdotes, we disdain those who are proud of their allegiance to a political party or ideology we abhor. We tire quickly of the person who trumpets their achievements and have even, thanks to social media, invented a term for pride when it cloaks itself in false humility: humble-bragging. How much play-acting does pride entail, and does the power it confers upon us stand up to moral scrutiny?

12. CYNICISM

We tend to think of cynicism as a defense mechanism, a form of psychological armor against false hope and its predictable consequences. While it poses as intellectual sophistication, cynicism tends to be used as a pejorative term. The fact is, we don’t like cynics, even when we secretly worry that their suspicions might be justified. The cynic, we say, sees only ulterior motives, virtue signaling, power plays, and damage control and looks askance at genuine acts of kindness, generosity, a change in heart, or activities aimed at improving conditions for society’s most vulnerable.

Yet cynicism once meant something very different; the word derives from the ancient Greek school of thought (κυνισμός) that challenged convention and taught simplicity and asceticism as strategies for resisting the corrupting influences of ownership, social status, power, and wealth. How did a philosophical attitude aimed at living a truer life stray so far from its original meaning? While the ancient Cynics located the source of moral deformity in false values and the artificiality of social norms and strove for a radical authenticity, modern cynicism views humanity itself as inherently deformed. Cynicism exists on a continuum; at one end is nihilism, which denies the existence of anything inherently good in humans that might serve as a basis for a universal code of ethics; at the other end of the spectrum is skepticism, which is colored by doubt but allows for the possibility that a given claim may be substantiated by evidence. Situated somewhere between the two, cynicism describes the jaded attitude of an individual who has come to mistrust the sincerity and integrity of others and regards the possibility the skeptic holds open as naive.

Peter Sloterdijk interpreted modern cynicism as the product of the Enlightenment’s defeat, a degradation of principles that once offered dignity and agency to the powerless. Increasingly, cynicism came to mean strategic thinking, the abuse of language, tactical maneuvering, and a deceptive appropriation of moral values to justify what are essentially self-serving interests. Cynicism’s language is scorn. It scoffs at the very possibility of human decency, negates the existence of higher ethical sentiment, and derides what it can only see as hypocrisy. Cynicism is a cognitive bias that is blind to human motives based on anything but egotism and personal advantage. Cynics are often disappointed idealists who once felt betrayed by their own beliefs. We see their cynicism for what it is: a defeatist position that masks a lack of vision and fear of risk with an aura of critical thinking that fails to engage in a constructive, factual manner with the matter at hand—and succumbs to its own distorted perception.

***

Part I of this project can be seen and read HERE

Part II of this project can be seen and read HERE

Images from the exhibition LOOPY LOONIES at Kunsthaus Graz, Austria, can be seen HERE