by John Hartley

How does Leonardo’s masterpiece, arguably representative of the fatal juncture of Western Art, provide the philosophical basis for pornography? And how does the lost work of an obscure German painter seek to correct what Pavel Florensky called ‘dis-integrated personality’?

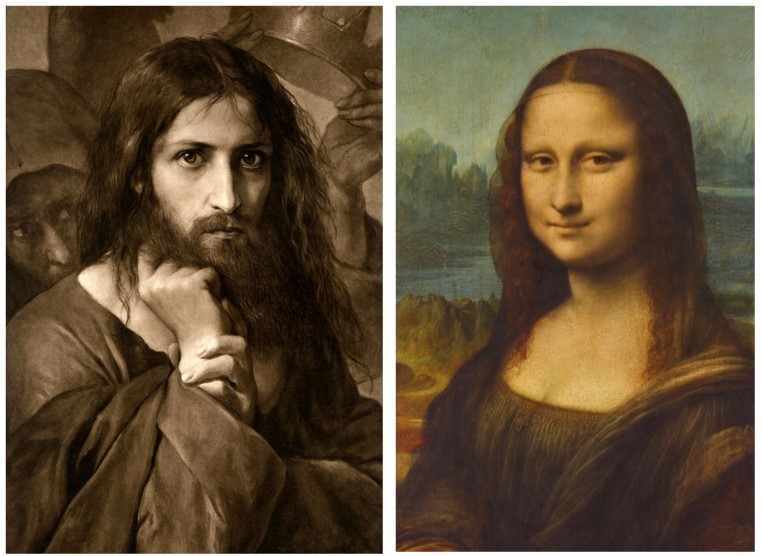

In 1888, Georg Cornicelius, a relatively obscure German artist known primarily for his landscapes, produced the portrait “Christ Tempted by Satan.” Cornicelius’ background in capturing vast vistas is brought to bear on Christ’s faculties of perception: the universal reality of nature is transposed upon the personal perspective of Christ.

In the third and final temptation in the wilderness, Satan offers Christ dominion over all the kingdoms of the earth if he will only bow down and worship him. The result of the interplay of proportions gives Christ’s eyes a striking depth—a metaphysical quality—that seems to penetrate the very essence of the beholder.

This temptation is profound, proposing a shortcut to salvation that bypasses the necessary suffering and sacrificial death Christ must endure for the sake of the world. According to St. James, temptation arises from concupiscence, the innate human proclivity towards moral evil. As Dostoevsky’s Grand Inquisitor accuses Christ of burdening humanity with the heavy responsibility of free will, and consequently responsible for the disordering of nature, Satan aims to arouse in Christ the concupiscence of the eyes—the desire for personal control over the visible world.

If evil arises as the will freely yielded to the one who seeks humanity’s eternal ruin, then all of temptation, it seems, is contained here within a single portrait. *Admittedly, there is a lack of critical opinion on this work (what would Morgan Meis make of this painting, one wonders?).

The Mona Lisa’s ‘Dis-Integrated’ Smile

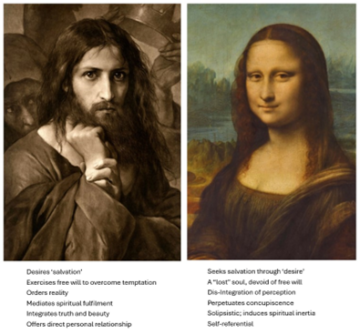

![]() In acute contrast, the desire for personal control over the visible world is most acutely manifest in Leonardo da Vinci’s “Mona Lisa.” Her elusive gaze is simultaneously inviting and distant, a temporal commitment betraying an integral duality. Her self-referential smile—which Freud famously described as possessing a “demoniac magic”—leads viewers into an abyss of their own insubstantiality, as the infinite regress of disintegrated perception.

In acute contrast, the desire for personal control over the visible world is most acutely manifest in Leonardo da Vinci’s “Mona Lisa.” Her elusive gaze is simultaneously inviting and distant, a temporal commitment betraying an integral duality. Her self-referential smile—which Freud famously described as possessing a “demoniac magic”—leads viewers into an abyss of their own insubstantiality, as the infinite regress of disintegrated perception.

To the Russian Orthodox polymath Pavel Florensky, her gaze embodies a corrupt inner turmoil devoid of repentance: a symbol of the soul’s lost state in self-idolatry. Her soul has become isolated, opaque, and disconnected from divine truth (and reality), insofar as it loses its capacity for genuine creativity and life, becoming a “lost” soul.

The refusal to disclose one’s true self leads to a fragmented existence, where the individual’s relation to God is distorted, leading to a disordered state characterized by a loss of spontaneous activity, freedom, and an integrated personality. The result is a passive existence where the surrounding world appears lifelike, but the individual remains detached and insensible.

In essence, Florensky uses the Mona Lisa’s mysterious smile as a metaphor for the human soul ensnared by sin—lost, isolated, and devoid of true repentance and connection to divine truth. The Mona Lisa’s refusal to reveal her secrets is a rejection of free will and the possibility of divine redemption.

The Decline of Western Art

The Mona Lisa remains a two-dimensional figure, forever out of reach, marking a departure in Western art from the medieval paradigm of presence to a modern passion of absence. In the past, religious sculpture and icons reminded viewers of God’s presence, engaging them in a direct, personal relationship. Icons were revered, seen as holy artifacts imbued with divine presence.

In contrast, the Mona Lisa exploits the surface’s sexual mystery, highlighting a lack of true connection between the viewer and the woman on the canvas. Leonardo’s masterful use of sfumato—the technique of blending colors and tones—underpins the enigmatic gaze that appears to follow the viewer, creating a pseudo intimacy that is (in contrast to Cornicelius’ Temptation of Christ) simultaneously obfuscating.

For Florensky, sin fundamentally involves a disruption of unity and a fragmentation of the holistic truth evident in the way individuals relate to each other and to the divine, resulting in a state of spiritual and moral disintegration: the distortion of truth and beauty. Sin is seen as a departure from this state of unity, leading to a form of existential isolation. This isolation is not only personal but also cultural, affecting how societies perceive and value truth, beauty, and goodness. Hence the decline of Western art.

Pornography as ‘Dis-Integrated’ Art

The modern phenomenon of pornography, in its essence, can be viewed as a manifestation of this spiritual and moral fragmentation. In reducing the human body to a mere object, it severs the holistic connection between physical beauty and spiritual truth. The unity of the human person is broken down into isolated parts meant to elicit a response from the viewer while simultaneously withholding oneself. Florensky would see it as a cultural and spiritual aberration that exemplifies the isolation and fragmentation inherent in sin.

For Florensky, the Western emphasis on rationality and logic often leads to a disintegration of holistic truth into fragmented, isolated facts. This approach, he suggests, is symptomatic of a deeper spiritual malaise where the interconnectedness of truth is lost. Pornography, with its focus on the disjointed and explicit portrayal of the human body, mirrors this rational fragmentation, stripping away the divinely ordained purpose and consequence of human sexuality. It can be therefore understood as an inversion of beauty, leading the soul away from divine truth.

Religious icons, in contrast, as windows to the divine, facilitate a connection between the viewer and the sacred. Yet pornography serves to distort and pervert this connection, turning the gaze inward towards selfish gratification rather than outward towards communion and spiritual ascent.

Both the icon and the pornographic image function as objects of direct personal relationship. They exist to elicit a response, lacking substance without it. They promise a form of fulfillment—whether libidinal or spiritual—both aim to transcend reality through their respective discourses: desire and salvation.

Concluding Remarks

Leonardo’s Mona Lisa, with her wayward ‘dis-integrated’ smile, encapsulates the shift from medieval icons’ passion of presence to modern art’s passion of absence.

Her mysterious allure reflects the viewer’s own passions and desires, leading them further into the self, ontological inertia, terminating in insanity (hence, arguably, the sharp increase of mental illness in the West). Leonardo, of course, presents his own alternative vision of art in his Salvador Mundi.

Cornicelius’ Christ serves as a corrective, calling us to renounce the concupiscence of the eyes—the desire for personal control over the visible world in favor of a divine communion and spiritual ascent.