by Brooks Riley

One of nature’s most endearing parlor tricks is the ripple effect. Drop a pebble into a lake and little waves will move out in concentric circles from the point of entry. It’s fun to watch, and lovely too, delivering a tiny aesthetic punch every time we see it. It’s also the well-worn metaphor for a certain kind of cause-and-effect, in which the effect part just keeps going and going. This metaphor is a perfect fit for one of the worst allisions in US maritime history, leading to the collapse of Baltimore’s Francis Scott Key Bridge after it was hit by the container ship MV Dali on the morning of March 26, 2024.

One of nature’s most endearing parlor tricks is the ripple effect. Drop a pebble into a lake and little waves will move out in concentric circles from the point of entry. It’s fun to watch, and lovely too, delivering a tiny aesthetic punch every time we see it. It’s also the well-worn metaphor for a certain kind of cause-and-effect, in which the effect part just keeps going and going. This metaphor is a perfect fit for one of the worst allisions in US maritime history, leading to the collapse of Baltimore’s Francis Scott Key Bridge after it was hit by the container ship MV Dali on the morning of March 26, 2024.

At that hour, long before dawn, it was too dark for the resulting ripple effect to be seen. But it was most certainly a hefty version of the pebble drop, with waves fanning out all the way to the harbor berth from which the Dali had just departed. At daybreak, when images of the disaster began to appear everywhere, the ripples were no longer visible. But given the catastrophic consequences of this event, and the tragic loss of life, they were, and still are, fanning out across the globe.

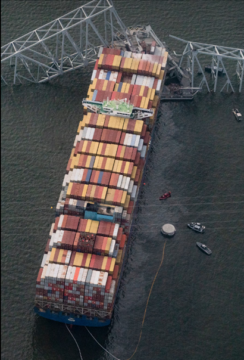

Am I the only one who can’t stop looking at images of this disaster? Am I the only one who sees an awful beauty in them? Or is it a beautiful awfulness? The frenzy of angles, the implosive intensity of the damage, the jolly Lego-like containers in Bauhaus colors still neatly stacked atop the ship in defiance of the tangled metal of the bridge’s cold steel mesh structure lying over the ship’s forecastle where it fell. Add to that the murky, shifting colors of the water, lending the disaster a visual context like a fluid frame—a calming contrast to the frozen pandemonium it encircles.

I can already imagine a photo series stretched out on the white walls of an art gallery somewhere—a catalog of contortions created by catastrophe. The eye is drawn to the obvious contrasts between ship and bridge. Colorful Maersk containers peek out from between twisted silver gray girders. The shape of the impact, its opposing trajectories, its freeze-frame immutability are all lovingly cradled in the amniotic fluid of the Patapsco River that surrounds them.

A ship and a bridge are conjoined—caught in a deadly embrace that will end only piece by piece as their union is dismantled. Until then, multiple versions of the image are repeated in every newspaper of the world.

The Dali was named after Salvador Dalí. Her sister ship is the Cezanne. Owned by a Japanese company, managed by a Singapore company, she was built by Hyundai in South Korea in 2015. In the world of globalized transportation, the use of a famous artist’s name may be practical—short, recognizable, easy to remember—with or without accents. Or it might reflect the whims of an art-loving shipowner.

In the case of the MV Dali, there’s a certain irony to its invocation of an artist. Nowhere in this pile-up are the icky curves of the painter’s notorious limp watches to be found. This is a clash of hard angles, challenging our notions of beauty with a chaotic version of its own. Still, the old surrealist might have appreciated the chaos and contrasts rendered by a turn of fate.

It’s not the first time that a catastrophic event has led to an unexpectedly aesthetic image. The once tasteless gothic arches at the base of the Twin Towers took on an eerie significance as they loomed over the rubble after 9/11—an image that went viral not only for its strange allure but also for its complicated commentary on worship. As Joseph Campbell once said, “You can tell what’s informing a society by what the tallest building is …” —in this case a cathedral of capitalism reduced to its ‘ecclesiastical’ foundations.

It’s not the first time that a catastrophic event has led to an unexpectedly aesthetic image. The once tasteless gothic arches at the base of the Twin Towers took on an eerie significance as they loomed over the rubble after 9/11—an image that went viral not only for its strange allure but also for its complicated commentary on worship. As Joseph Campbell once said, “You can tell what’s informing a society by what the tallest building is …” —in this case a cathedral of capitalism reduced to its ‘ecclesiastical’ foundations.

I first thought of the Baltimore images as emblematic: Globalization meets its weakest link. Globalization trounces localization. Clash of the conduits. Superstructure meets Infrastructure. There’s more than one tabloid headline lurking in that pile of contrasts. It seems too pat to sound the alarm we’ve heard so many times before: ‘Globalization leads to catastrophe.’ Were it only that simple. Globalization also provides a livelihood for millions if not billions of people. And while these images can serve up a variety of homegrown caveats, they lose their magic in minutes.

What remains is the violent visual impact of a singular event—one that seemed to unfold in slow motion. It was the first thing I saw when I went online on the morning of March 26 CET, not long after the crash. A video starting at 1:23:13 a.m. EDT shows the dark outline of a bridge with the headlights of a few vehicles crossing it. A dark shape is moving slowly toward the center shipping lane between the pylons, backlit by the harbor lights. Its own lights suddenly turn off, then on again, and then off, followed by impact at 1:28:44. Seconds later the bridge collapses with the ease of a Jenga miscalculation.

The illusion of slow motion is what makes this video so compelling. Moving at only 8 knots (9 mph) when an electrical failure killed its engines, the massive container carrier soon began to drift inexorably closer to a bridge pylon. The lights came back on after a minute and the engines managed a massive reverse thrust (which sent black smoke billowing into the sky) before a second blackout killed both its engine and presumably also its bow thruster, that modern miracle maneuverer whose propellers might have saved the day by pushing the bow away from the pylon. The two harbor pilots still on board tried in vain to drop anchor to minimize the impact. Even in a long shot, the path of inevitability is obvious and terrifying. There was just enough time to close the bridge to traffic, but six of the men working on its roadbed tragically fell to their deaths.

***

Any encounter with an artistic image sets up an equation: One half is the work itself. The other half is the backstory of its beholder. In this case, I may indeed be the only one who can’t stop looking at these images, because of a maritime history of my own that rises to the surface when I look at them. Not only was my childhood peppered with transatlantic crossings on big ships, I continued to nurse a passion for them well into adulthood. I even skipped classes to sneak on board ocean liners docked on Manhattan’s west side. I spent a day on a Moran tugboat as it maneuvered freighters from their docks in Brooklyn and Manhattan, interviewing the crew and seeing the ships up close from under their bows, filming with a borrowed 16mm camera.

I cannot see an image of an ocean-going vessel without a pang of the intense love I once felt for them, even years after I turned my attention elsewhere. Ocean-going vessels were the carriers and nurturers of a grand solitude that I found irresistible. Losing oneself on a sea of no context persisted as an ideal that haunted me for years.

***

Container ships are not the ugliest vessels plying the oceans. Highly functional, their lines are sleek and simple, adhering to basic nautical design—unlike the bathtub obesity of floating playgrounds like the Icon of the Seas. Container ships stick to their mandate, carrying as many 20-foot containers as possible to ports all over the world. They are the conduits that keep the world’s goods flowing smoothly from producer to consumer—boring but necessary.

The MV Dali is a middle-sized container ship. She is as wide as a football field and nearly three times as long. She can carry 10,000 twenty-foot containers. The world’s largest container ship, the MSC Irina, is 200 feet wide, nearly four times the length of a football field and can carry 24,000 containers.

If early long shots of the accident offered an artistic junction of opposing forces in placid waters, close-ups of the damage expose the explosive fury of impact—a concrete pier piercing the starboard side of the bow (I catch myself clutching my right side), a gaping hole right next to it, both mercifully above the water line.

As photogenic as the first images of the collision were, few managed to capture the magnitude of the disaster. Now that the untangling process is underway, cameras have gotten closer and begun to chronicle the complicated task of severing the two protagonists, allowing us to experience its scale through some unexpected measuring devices—such as the four lanes of the bridge’s roadbed draped comfortably across the bow of the ship.

A high-stakes blame game has begun with a salvo from the Port of Baltimore, holding the ship responsible for departing before its electrical problems had been thoroughly resolved.

But the theory that ‘if something can go wrong, it will’ should haunt all administrators of harbors in the world of supersized shipping. The Francis Scott Key Bridge, completed in 1977 before structural redundancy requirements, seems not to have been fortified even as the harbor welcomed bigger and bigger ships. No serious safeguards like riprap were placed around pylons as preventative measures for such an eventuality. The dolphins, buoy-like fenders randomly placed nearby, were not in the ship’s errant path. It may also be that nothing stationary could have prevented the bridge’s collapse.

If there was error that night, it was an outdated protocol. A complete blackout on a ship may be extremely rare, but engine failure from contaminated fuel is increasingly common. Given the narrowness of the bridge’s span over the shipping lane, to have allowed a ship the size of the Dali to clear the fracture critical bridge without at least one tugboat still on hand is inconceivable. In contrast, New York’s Verrazzano Narrows Bridge boasts a span three and a half times the length of the Baltimore bridge’s span. And according to Wikipedia, authorities are ‘confident that riprap, or piles of rocks, around the [suspension] towers’ bases would ground a stray ship before it could hit a tower.’ Even so, some weeks after the Baltimore bridge collapse, another container ship suffered engine failure as it was leaving New York harbor and was immediately escorted by three tugboats, who maneuvered it into circles, away from the Verrazzano bridge, until it could berth at Stapleton Anchorage for overnight repairs.

According to the Washington Post, ‘there is no single standard for the use of tugs to escort large ships in and out of ports in the United States’. This is shocking, given that tugboats would have been the Francis Scott Key’s best—and possibly only—line of defense.

***

There’s something profane, but at the same time exhilarating, about finding beauty in destruction. Artists like Anselm Kiefer, who grew up playing in the ruins of World War Two, have no problem attacking their own works as part of the process of completion—applying corrosive substances or blowtorching canvases like strokes of malevolent fate. Their beauty is paradoxical but intentional, achieved through highly controlled acts of destruction.

But when a catastrophic event—in this case a tragic one—enters the rarefied visual spectrum of artistic merit, it’s almost a sacrilege to dwell on the powerful aesthetics that may be associated with it. Beauty and terror often go hand in hand, but there’s a limit to our appreciation of something which has caused such devastating consequences, or so much pain and grief.

Loss of life is a major part of the story. But a damaged container full of cardboard boxes of various sizes also points to thousands of micro-narratives that have been redacted by the catastrophe—people waiting for that all-important package that never arrives, businesses waiting for essential materials or replacement parts. Add to this the many jobs lost, the loss of easy access across a city, the economic losses for the port, the city, the nation, and for the ship itself, and one begins to sense the extent of the reverberations. The ripple effect is no longer lovely and fun. It is sinister.

As Immanuel Kant once stated, “We see the world and things not as they are but as we are.” There may be no better explanation for the aesthetic experience than that. But his statement reaches far beyond the realm of personal perception. As the planet slowly drifts, like the powerless MV Dali, toward an apocalyptic future brought on by climate change, it might be better to acknowledge a darker vision of how things are—and shore up our bridges.

***

Notes: There has been massive coverage of this event. Here are a few recommendations:

The New York Times’ extensive coverage included an excellent analysis of the astounding physics behind such a devastating blow to the bridge

The Washington Post’s analysis of the bridge’s safety—and their first comprehensive reportage from the day of the accident

A cottage industry of investigative videos has materialized on YouTube. Here are a few of the better channels:

The YouTube channel Beyond Facts offers two detailed versions of what happened, both impressive in spite of some illustrative errors: Baltimore Bridge Disaster – What REALLY Happened and How One Error Caused The Baltimore Bridge Disaster

The YouTube channel Practical Engineering offers a professional overview: How Bridge Engineers Design Against Ship Collisions

On a personal note, this charming Encyclopedia Britannica Films documentary about a Moran tugboat captain was shot a short time before my Moran tugboat film (which was never finished). It offers a similar view of what it was like in New York Harbor at that time.

An official website monitors the clean-up operation and offers updates

And lastly, a closer look at my maritime history.