by Lisa Lieberman

“Trauma's never overcome,” Melvin Jules Bukiet asserted in The American Scholar. Redemptive works of literary fiction—or “Brooklyn Books of Wonder” (most of the authors he excoriated in the essay, including Alice Sebold, Jonathan Safran Foer, Myla Goldberg, Nicole Krauss, and Dave Eggers, hailed from the borough)—provide mock encounters with enormity. Wooly mysticism blunts the force of death and violence, expunging cruelty and indifference. Legitimate feelings of grief and rage are muffled in sentimentality. But the comfort these healing narratives offer is not only superficial. It is a travesty:

Your father is dead, or your mother, and so are most of the Jews of Europe, and the World Trade Center's gone, and racism prevails, and sex murders occur. What is, is. The real is the true, and anything that suggests otherwise, no matter how artfully constructed, is a violation of human experience.

Bukiet, the son of Holocaust survivors, preferred the open wound. He and other members of the so-called second generation were marked by their parents' ordeal. The ghetto, the lager, the devastating losses of an older generation who could not communicate their experiences: no matter how hard survivors's children tried to imagine life on the other side of the barbed wire, their efforts fell short of the truth. Their reconstructions, in the telling phrase of another second generation author, Henri Raczymow, were shot through with holes. Why bring closure to suffering that has no end?

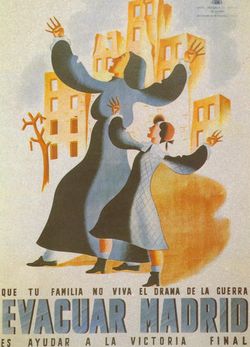

Other twentieth-century catastrophes have marked the descendants of those who lived through them, the Spanish Civil War (1936-39) especially.  Outside of Spain, idealized treatments are abundant, Hemingway's For Whom the Bell Tolls and Malraux's L'Espoir upstaging Orwell's hard-nosed account, Homage to Catalonia. But within Spain itself, artistic renderings of the event have been more nuanced, resisting the trivializing sentimentality of the Brooklyn-Books-of-Wonder approach until fairy recently (Belle Epoque, which won the Oscar for best foreign language film in 1994, comes to mind).

Outside of Spain, idealized treatments are abundant, Hemingway's For Whom the Bell Tolls and Malraux's L'Espoir upstaging Orwell's hard-nosed account, Homage to Catalonia. But within Spain itself, artistic renderings of the event have been more nuanced, resisting the trivializing sentimentality of the Brooklyn-Books-of-Wonder approach until fairy recently (Belle Epoque, which won the Oscar for best foreign language film in 1994, comes to mind).

The Spirit of the Beehive (1973) was the first film to address the trauma of the Spanish Civil War, which it presented obliquely, through the eyes of a child. In part this was necessary to evade the censors; the dictator Francisco Franco still ruled Spain when Victor Erice made the film. But the story, which Erice wrote as well as directed, was intensely personal. “Erice and co-screenwriter Ángel Fernández Santos based the script on their own memories,” Paul Julian Smith revealed in his Criterion essay on the film, “recreating school anatomy lessons, the discovery of poisonous mushrooms, and the ghoulish games of childhood. It is no accident that the film is set in 1940, the year of Erice's own birth.”

Read more »

I moved to Berlin in 1984, but have rarely written about my experiences living in a foreign country; now that I think about it, it occurs to me that I lived here as though in exile those first few years, or rather as though I’d been banished, as though it hadn’t been my own free will to leave New York. It’s difficult to speak of the time before the Wall fell without falling into cliché—difficult to talk about the perception non-Germans had of the city, for decades, because in spite of the fascination Berlin inspired, it was steeped in the memory of industrialized murder and lingering fear and provoked a loathing that was, for some, quite visceral. Most of my earliest friends were foreigners, like myself; our fathers had served in World War II and were uncomfortable that their children had wound up in former enemy territory, but my Israeli and other Jewish friends had done the unthinkable: they’d moved to the land that had nearly extinguished them, learned to speak in the harsh consonants of the dreaded language, and betrayed their family and its unspeakable sufferings, or so their parents claimed. We were drawn to the stark reality of a walled-in, heavily guarded political enclave, long before the reunited German capital became an international magnet for start-ups and so-called creatives. We were the generation that had to justify itself for being here. It was hard not to be haunted by the city’s past, not to wonder how much of the human insanity that had taken place here was somehow imbedded in the soil—or if place is a thing entirely indifferent to us, the Earth entirely indifferent to the blood spilled on its battlegrounds.

I moved to Berlin in 1984, but have rarely written about my experiences living in a foreign country; now that I think about it, it occurs to me that I lived here as though in exile those first few years, or rather as though I’d been banished, as though it hadn’t been my own free will to leave New York. It’s difficult to speak of the time before the Wall fell without falling into cliché—difficult to talk about the perception non-Germans had of the city, for decades, because in spite of the fascination Berlin inspired, it was steeped in the memory of industrialized murder and lingering fear and provoked a loathing that was, for some, quite visceral. Most of my earliest friends were foreigners, like myself; our fathers had served in World War II and were uncomfortable that their children had wound up in former enemy territory, but my Israeli and other Jewish friends had done the unthinkable: they’d moved to the land that had nearly extinguished them, learned to speak in the harsh consonants of the dreaded language, and betrayed their family and its unspeakable sufferings, or so their parents claimed. We were drawn to the stark reality of a walled-in, heavily guarded political enclave, long before the reunited German capital became an international magnet for start-ups and so-called creatives. We were the generation that had to justify itself for being here. It was hard not to be haunted by the city’s past, not to wonder how much of the human insanity that had taken place here was somehow imbedded in the soil—or if place is a thing entirely indifferent to us, the Earth entirely indifferent to the blood spilled on its battlegrounds.