by Ed Simon

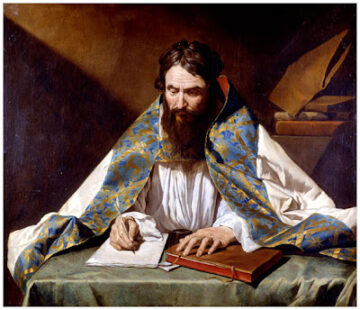

As an émigré from the dusty, sun-scorched Carthaginian provinces, there are innumerable sites and experiences in Milan that could have impressed themselves upon the young Augustine – the regal marble columned facade of the Colone di San Lorenzo or the handsome red-brick of the Basilica of San Simpliciano – yet in Confessions, the fourth-century theologian makes much of an unlikely moment in which he witnesses his mentor Ambrose reading silently, without moving his lips. Author of Confessions and City of God, father of the doctrines of predestination and original sin, and arguably the second most important figure in Latin Christianity after Christ himself, Augustine nonetheless was flummoxed by what was apparently an impressive act. “When Ambrose read, his eyes ran over the columns of writing and his heart searched out for meaning, but his voice and his tongue were at rest,” remembered Augustine. “I have seen him reading silently, never in fact otherwise.”

As an émigré from the dusty, sun-scorched Carthaginian provinces, there are innumerable sites and experiences in Milan that could have impressed themselves upon the young Augustine – the regal marble columned facade of the Colone di San Lorenzo or the handsome red-brick of the Basilica of San Simpliciano – yet in Confessions, the fourth-century theologian makes much of an unlikely moment in which he witnesses his mentor Ambrose reading silently, without moving his lips. Author of Confessions and City of God, father of the doctrines of predestination and original sin, and arguably the second most important figure in Latin Christianity after Christ himself, Augustine nonetheless was flummoxed by what was apparently an impressive act. “When Ambrose read, his eyes ran over the columns of writing and his heart searched out for meaning, but his voice and his tongue were at rest,” remembered Augustine. “I have seen him reading silently, never in fact otherwise.”

Such surprise, such wonderment would suggest that something as prosaic as being able to read silently, free of whispering lips and finger following the line, was a remarkable feat in fourth-century Rome, so much so that Augustine sees fit to devote an entire paragraph to his astonishment. Both men were exemplary theologians, Church Fathers, and eventually saints, but only Ambrose was able to accomplish this simple task which you’re most likely doing right now. For Ambrose – as for you and me and billions of other literate people the world over – literacy allows for a cordoned off portion of the self, a still mind as if an enclosed garden from which words may be privately considered, debated, ,or enjoyed, while for Augustine, by contrast, all of those millions of arguments he constructed could only be uttered aloud by their author, and by the vast majority of his readers. Read more »