by Jochen Szangolies

I have once again been thinking about power, and once again I feel ill at ease with it. Yet while I do consider myself somewhat badly equipped for this pursuit, I nevertheless feel, “in these trying times”, a certain responsibility to not cozy up with pursuits closer to my heart and talents, but invest some portion of my time and ability into examining the mechanisms of control as they are exerted in the world. After all, as before, one may hope that slow and steady going may substitute for knack and knowledge, and perhaps even help those otherwise sidelined to enter the conversation.

The prompt for the present swerve out of my lane was provided by a colleague’s lunchtime question, after the conversation had inevitably landed on the topic of what flavor of future dystopia awaits. “But how,” he started (or nearly enough so), “are the billionaires in their bunkers going to keep themselves in charge?” After all, what’s to stop the armies of servants they depend upon to uphold their lavish lifestyles from just, well, murdering them and taking their shit?

The question invites an immediate followup: what’s stopping us now? Not murdering, as such—but even just applying equal standards to the wealthy stands to free up resources capable of addressing a great many injustices in the world. According to a recent estimate by the US Department of the Treasury, the top 1% of earners dodge about $163 billion in annual taxes. (If you, like virtually everyone, have trouble conceptualizing these sorts of numbers, I find it helps to convert them to time scales: if a dollar is a second, then a million dollars are about eleven and a half days, while a billion dollars are roughly 31.7 years; the avoided sum of taxes then takes us back 5165 years, back to when the first phases of Stonehenge started construction. By contrast, the median US income for a full-time worker is about $63,000, or roughly 17.5 hours.)

Clearly, there is much good that could be done with that sort of money. As a semi-random example, according to estimates it would take from 10 to 30 billion dollars annually to end homelessness in the US, essentially eradicating a major source of suffering. And nobody would have to get murdered—or even unduly inconvenienced: this is money that is already legally owed, simply by having the 1% pay their fair share. Studies project an added revenue of up to $12 dollars per dollar invested in audits of high income individuals. So why aren’t we out there demanding equal treatment for the wealthy? Read more »

Consider again the wooden desk. It was once part of a tree, like the ones outside your window. It became a bit of furniture though a long process of growth, cutting, shaping buying and selling until it got to you. You sit before it as it has a use – a use value – but it was made, not to give you a platform for your coffee or laptop, but in order to make a profit: it has an exchange value, and so had a price. It is a commodity, the product of an entire economic system, capitalism, that got it to you. Someone laboured to make it and someone else, probably, profited by its sale. It has a history, a backstory.

Consider again the wooden desk. It was once part of a tree, like the ones outside your window. It became a bit of furniture though a long process of growth, cutting, shaping buying and selling until it got to you. You sit before it as it has a use – a use value – but it was made, not to give you a platform for your coffee or laptop, but in order to make a profit: it has an exchange value, and so had a price. It is a commodity, the product of an entire economic system, capitalism, that got it to you. Someone laboured to make it and someone else, probably, profited by its sale. It has a history, a backstory. All of this is the case, but none of it simply appears to the senses. Capitalism itself isn’t a thing, but that doesn’t make it less real. The idea that all that there really is amounts to things you can bump into or drop on your foot is the ‘common sense’ that operates as the ideology of everyday life: “this is your world and these are the facts”. But really, nothing is like that: there are no isolated facts, but rather a complex, twisted web of mediations: connections and negations that transform over time.

All of this is the case, but none of it simply appears to the senses. Capitalism itself isn’t a thing, but that doesn’t make it less real. The idea that all that there really is amounts to things you can bump into or drop on your foot is the ‘common sense’ that operates as the ideology of everyday life: “this is your world and these are the facts”. But really, nothing is like that: there are no isolated facts, but rather a complex, twisted web of mediations: connections and negations that transform over time.

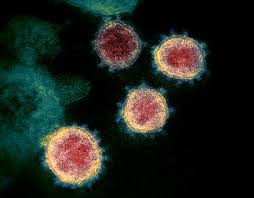

The current Covid 19 pandemic is undoubtedly a disaster for millions of people: for those who die, who grieve for the dead, who suffer through a traumatic illness, or who, suddenly lacking work and income, face the prospect of dire poverty as the inevitable recession kicks in. And there are other bad consequences that one might not describe as ‘disastrous” but which are certainly significant: the stress experienced by all those providing care for the sick; the interruption in the education of students; the strain put on families holed up together perhaps for months on end; the loneliness suffered by those who are truly isolated; and the blighted career prospects of new graduates in both the public and the private sectors.

The current Covid 19 pandemic is undoubtedly a disaster for millions of people: for those who die, who grieve for the dead, who suffer through a traumatic illness, or who, suddenly lacking work and income, face the prospect of dire poverty as the inevitable recession kicks in. And there are other bad consequences that one might not describe as ‘disastrous” but which are certainly significant: the stress experienced by all those providing care for the sick; the interruption in the education of students; the strain put on families holed up together perhaps for months on end; the loneliness suffered by those who are truly isolated; and the blighted career prospects of new graduates in both the public and the private sectors.