by Brooks Riley

Something odd happens when I look at the elder Pieter Bruegel’s paintings: I experience a jolt of vertigo, as though I’d stepped out on a ledge somewhere—not too high up, but high enough to initiate a physical reaction more like titillation than terror. I didn’t notice this right away: For a long time, I was too busy taking in all the business going on in those paintings: the crowds, the tussles and bustle of the marketplace, the hawkers, the wagons, the houses, the animals, and in some of his works a topography rather alien to his own very flat province of North Brabant in the Netherlands. A master of ‘everything everywhere all at once,’ Bruegel knew how to crowd a wooden panel.

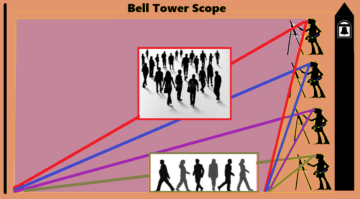

In The Fight between Carnival and Lent, faced with a multitude of finely-rendered characters alive with attitude, it’s easy to be distracted from the shot itself—its acute angle, its distance from the action, its extended scope and high horizon achieved through elevation. This is a classic content-over-form dialectic that faces every viewer looking at a painting. What am I seeing? What am I supposed to see? Where am I seeing from?

In this case ‘where am I seeing from’ has everything to do with ‘what am I seeing’’: It’s the high oblique angle that enables the viewer to take in all those individuals spread out over the market square. (An AI command to make each character look up at the painter, might force the viewer to think about where Bruegel is situated as he paints, even if he’s up there only in his imagination. It’s like the fourth wall: you’re unaware of it until a character turns and speaks to you directly.)

A cinematographer would recognize this as a crane shot, or its replacement, the drone shot. This crane or drone doesn’t move. It defines the POV (point of view) of the painter, and shows how far his perspective can reach and how much he can cram into the in-between, that 2D surface which expands vertically with every higher angle of his POV, as in this crane shot from Gone with the Wind.

A cinematographer would recognize this as a crane shot, or its replacement, the drone shot. This crane or drone doesn’t move. It defines the POV (point of view) of the painter, and shows how far his perspective can reach and how much he can cram into the in-between, that 2D surface which expands vertically with every higher angle of his POV, as in this crane shot from Gone with the Wind.

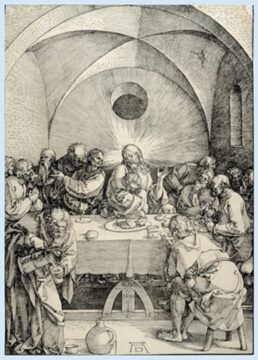

The issue of POV has been around a long time. Dürer faced it too: How can I depict the Last Supper in such a way that all 12 apostles sitting at the table are visible? Leonardo da Vinci’s theatrical solution had been to put everyone on one side of a table elongated to stretch-limousine length: Jesus and the 12 disciples all in a row, at eye level. All that’s missing are footlights.

In a woodcut from 1510, Dürer arrived at a different solution by elevating his point of view to that of the fly on the wall, high up enough that every guest at the table gets his 15 square millimeters of fame. As if to prove his point, Dürer crowds Jesus and the twelve apostles around a tiny table, replacing the solemnity of the occasion with informality and what looks like horseplay, considering Jesus’s chokehold on one of them. Even that iconic AD signature, ‘embedded’ on the floor, would only be visible from his chosen elevation.

In a woodcut from 1510, Dürer arrived at a different solution by elevating his point of view to that of the fly on the wall, high up enough that every guest at the table gets his 15 square millimeters of fame. As if to prove his point, Dürer crowds Jesus and the twelve apostles around a tiny table, replacing the solemnity of the occasion with informality and what looks like horseplay, considering Jesus’s chokehold on one of them. Even that iconic AD signature, ‘embedded’ on the floor, would only be visible from his chosen elevation.

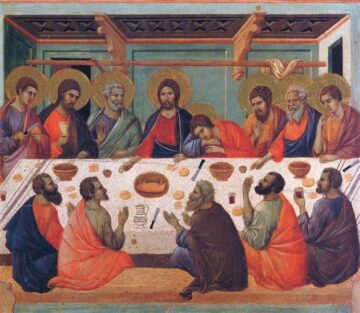

Dürer wasn’t the first painter to try to solve the Last Supper problem: In 1311 Duccio chose to tilt the table, with half the guests standing behind it and the other half sitting in the foreground. Suspension of gravity, a side-effect of this arrangement, allowed the food and drink to cling to the surface way beyond their tipping point. Duccio didn’t know that raising his own point of view would have solved everything.

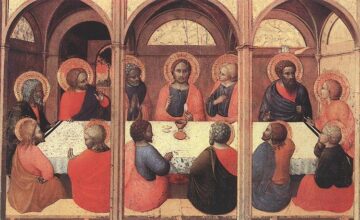

Il Sassetta almost got it right in 1423, but his figures on the far side of the table are too tall or on the near side, too short. (Bosch didn’t get it either.) There’s a lot of table-tilting and deathbed-tilting in the early Renaissance, as painters inched ever closer to the surprisingly elusive solution of an elevated POV.

Rogier van der Weyden seemed to get it in his Seven Sacraments Altarpiece, (1445-50). Each of the three panels offers a different elevation, as though he were experimenting to find the optimal angle for viewing multiple occurrences along a depth of field. Some of the perspective adjustments are off, but the overall effect is surprisingly dynamic and functional.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder was one of the first Western artists to intuitively understand POV, a few years after Dürer. I can imagine Bruegel as a boy, climbing the newly rebuilt bell tower of the Grote Kerk in Breda to watch the marketplace below. What better inspiration for an incipient painter than to see so many objects and people artfully spaced within the canvas of his downward gaze! Forget the sky. He often did.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder was one of the first Western artists to intuitively understand POV, a few years after Dürer. I can imagine Bruegel as a boy, climbing the newly rebuilt bell tower of the Grote Kerk in Breda to watch the marketplace below. What better inspiration for an incipient painter than to see so many objects and people artfully spaced within the canvas of his downward gaze! Forget the sky. He often did.

Being up there in the bell tower would also have given him ample opportunity to study perspective and distance, so problematic among Renaissance painters, even Da Vinci and Dürer, who tended to squeeze too many kilometers into their landscapes.

Bruegel seemed to know just how far the eye can see. The road in Hunters in the Snow is easy to follow as it meanders out of town and then turns left and continues on to its endpoint in the visual field. It’s completely natural, as authentic as a photo, its perspective perfectly in synch with the angle of his POV—not contrived, like some studio concepts of distance, as seen behind the Mona Lisa or behind Dürer in his Self-portrait at 26.

For someone from the Low Countries, the bat-in-the-belfry lure of altitude must have been irresistible. One of Bruegel’s most vertiginous paintings—based on the two existent copies—refers to the legendary fall of Icarus from a great height into the sea. But the painting’s vertigo is induced elsewhere, as we and Bruegel hover, with drone’s-eye vision, over a ploughman in the foreground working a downhill plot of land precariously near a precipice. He dominates the painting. It’s as if Bruegel wanted to say, mythology has its falls, we mortals might have ours. They are shorter but just as deadly. A shepherd with his back to the precipice looks up, presumably at Daedalus: Put a smartphone in his hand and he might have backed up far enough to join Icarus in a watery death.

The painting gives top billing to Ovid’s witnesses, the simple working men who may or may not have seen the wannabe birdman of myth splash down. All that’s seen of Icarus are two legs and a hand protruding from the water. But the witnesses pay no attention to him. For them, he’s just another casualty in a life full of them. Speaking of this painting, one Belgian curator referred to an old German saying: ‘No plough stops for the sake of a dying man.’

Bruegel’s genius was just beginning to emerge as he commandeered the vertigo view from the birds, the bats and the flies, to produce works that also included bucolic landscapes. Many of his paintings were small-town urban and densely populated. When he painted outside town walls, he brought the same folk to populate the landscapes. And he was always above it all, elevated to greater or lesser degrees. Even when he seems to have dropped down to ground level, there’s always a slight elevation that gives him the advantage of revealing subjects hidden in the background. (The Peasant Wedding, The Wedding Dance).

What raises Bruegel so far above his peers is his spatial aptitude, his innate understanding of perspective at any elevation, from any POV. Given the unimpressive vistas of his master Pieter Coecke van Aelst, Bruegel couldn’t have been taught these things; he must have arrived at them through observation—from that bell-tower in Breda or an Alpine road on his way to Italy. He then internalized what he learned, so that the laws of perspective came naturally to him. Bruegel’s access to an inner drone gave him wings to fly, like Icarus, without falling or failing or ever leaving his atelier.

Those same powers of observation gave him a remarkable grasp of human movement—at any distance. One casual miracle in Hunters in the Snow: the skaters on the lake, whose stances are immediately familiar, with only a few spare brush strokes. Bruegel understood the subtleties of body language and attitude from every angle and in every human endeavor, whether it was ice-skating, dancing, or gesturing, up close or far away.

Faced with a dearth of biographical information, scholars keep trying to pin Bruegel to a privileged class. He may have moved into those circles after he became famous (much like Dürer did), but his noteworthy familiarity with the kinesthetic vocabulary of the peasant class, suggests a milieu he knew from experience.

The hilly terrain in Hunters in the Snow doesn’t exist in the Netherlands, but Bruegel needed those hills to broaden the scope of the painting—to lay bare the layers of activity going on at every point in the distance. He even needed to be elevated above the hunters—his foreground protagonists—in order to arrive at the full visibility of his imagined view. He stops short of showing us the area of descent the hunters are headed for: It could be a cliff or a gentle hillside, as is implied. Purity of scale mattered to Bruegel. He knew when to stop.

***

As earthbound creatures, we harbor an instinctive, subconscious envy of birds—their freedom of flight, their exclusive views of the world. Those views are now being replicated by drones for both cinematography and still photography, launching an aesthetic of its own that includes vertical drone photography, which uses a full 90-degree angle to record the beauty of abstract patterns on the earth’s surface, from crowded beaches to waterways, from pine forests to sand dunes.

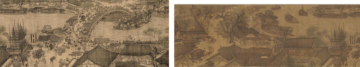

The Chinese were already imagining such an extreme angle a millennium ago, as seen in this bird’s eye view of a procession:

The angle isn’t quite vertical, allowing shapes to exist where mostly shadows would have been discernible. As drone photo, this procession would fall somewhere between this 90-degree angle. . .

. . . and this ca. 45-degree angle:

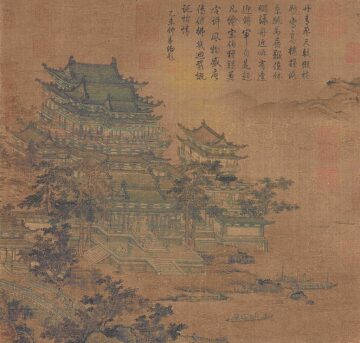

At a time when Western art was struggling with perspective and the elusive verisimilitude of alternative POVs, artists in China and Japan had long since mastered the many oblique angles with which to observe a scene, most of them above their subjects. The 8th-century artist Li Zhaodao precisely rendered the architecture of a building from a higher angle. A drone couldn’t have improved on what Li managed to reproduce from his imagination (or an elevation).

The 12th century Chinese artist Zhang Zeduan was right at home with an elevated POV, his perspective astonishingly accurate, without the ‘tilt’ effect so often seen in Renaissance paintings. And like Bruegel four centuries later, Zhang had no difficulty with crowds:

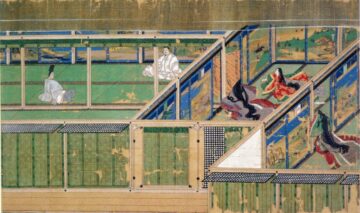

The drone aesthetic didn’t just apply to landscapes: The Genji Monogatari Emaki from the 12th century utilizes a form of composition known as fukinuki yatai (“blown-off roof”) that allows an overhead view of the interior and exterior of a building, a perfect device for a novel like Tale of the Genji.

Fukinuki yatai persisted for centuries, as a way of adding narrative intrigue and spatial diversity to a painting. The 14th century Japanese painter Takashina Takakane’s work bristles with drama on either side of the exposed walls:

What is it about the drone aesthetic that captures the artistic imagination? Beyond the urge to see the big picture, it may have been to get more information than could be grasped at ground level. (This is certainly true of Bruegel). It may also have been to gain some distance from the subjects. Some elevations in early Japanese art look like voyeurism, the artist capturing his subject at an extreme angle the way a hidden camera might.

The many oblique angles used by early Asian artists were proto-cinematic. Story-telling scrolls like Takashina Takakane’s Kasuga Gongen Genki E offer a variety of stagings, like individual camera shots, to add to the dramatic effect. All that’s missing is for the POV to move like a motion picture. A dormant, biological need for cinema could be inferred, many centuries before the movies finally satisfied that need. The scrolls themselves are proto-cinematic, with a story that keeps unfolding (unrolling) before a fixed point—like a reel of film.

In the West, perspective was treated as a straight-ahead issue, as we see in Da Vinci’s Last Supper or his Annunciation. But perspective changes with every variation of POV. Western artists didn’t adapt as well as their forerunners in the East because they didn’t often abandon the straight-on view. Their concerns lay elsewhere—in color, detail, composition and realism. Da Vinci’s bespoke realism might mean the sfumato that made his subjects look alive. Dürer’s eye for detail might mean the down of a hare, the window reflected in his iris, a stunning clump of weeds or a pillow.

The history of art is full of anomalies. Bruegel was lucky to thrive in a period when religious imagery was on the wane and genre painting was becoming popular, giving his simple folk pride of place in homes of the wealthy.

Bruegel may have been the first Western artist to treat art as a form of entertainment. His masterpieces celebrate not only the wit of the moment but also the various lives being lived simultaneously within one frame. That all-inclusive, humanistic view owes everything to the oblique angles he chose to make it all possible—the angles that gave everyone their moment without abandoning the incomparable beauty of the scene as a whole.

From somewhere over our heads, Bruegel gave us a new way to see, long before drones. Centuries later, it is a gift that keeps on giving.