That, I assume, is the floor slab of a demolished industrial building. It’s located near one of the remaining fragments of the Morris Canal in Jersey City. Back in the day the Morris Canal delivered anthracite coal from Eastern Pennsylvania to New Jersey and New York City – the Hudson River is no more than half a mile to the right of this slab. Things have changed; the Morris Canal was abandoned in 1924. I don’t know just when guerilla skate boarders appropriated this slab for their sport, but I took the photo at 6AM on July 30, 2011. One feature in this do-it-yourself (DIY) skate park remains unfinished – that pile of dirt and rock to the right of center. Notice the Myspace URL at the bottom of the photo.

DIY parks have been an aspect of skate boarding for a long time. There aren’t enough purpose-built parks to meet the demand. People don’t like skate boarders using public sidewalks, plazas, parks, shopping centers, and streets, and skate boarders don’t like be harassed for doing what they love. What to do? Find an out-of-the-way spot and build your own park, that’s what.

I have no idea how many laws were broken in creating and using this park. The spot is a little out of the way, but only a little. It’s clearly visible from the light rail train that runs 100 yards away. But officials were content to look the other way and apparently the landowners didn’t care – perhaps the city owned the land.

It may be illegal, but the park existed – it is no more – for the public good. It kept skate boarders, and BMX bicycle riders, out of the way, and harmed no one. As long as no one is being harmed, the sensible thing to do is to look the other way.

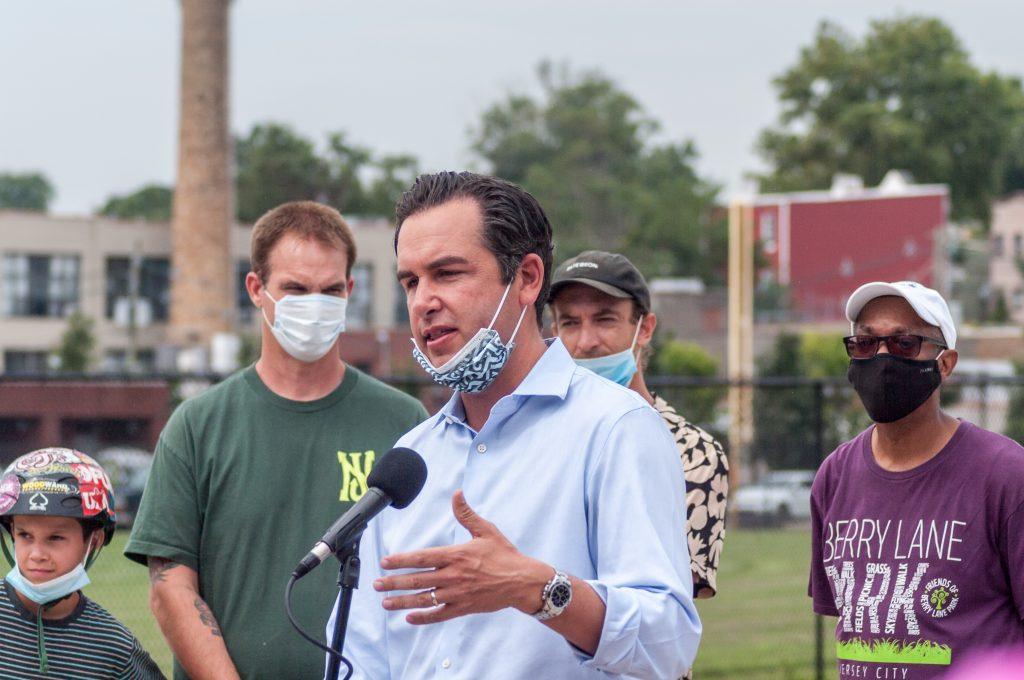

At the time I took that photo I had been about four years into an effort to create a public poured-in-the-ground skate park in Jersey City. That effort finally came to fruition last Thursday, on August 6, 2020. At the center of the photograph we see Jersey City’s mayor, Steve Fulop, speaking at the opening of the park. The man to the left is Steve Leonardo, who owns a local skate shop and who helped the city obtain a grant from the Tony Hawk Foundation to build the park. The man to the right – didn’t get his name, I wasn’t taking notes – represents the Friends of Berry Lane Park, a citizen’s group that keeps an eye on the larger park in which the skate park is located. You’ll see the man behind the mayor in one of the photos later in the article.

Once upon a time…

Back in 2006, when I was living in the Hamilton Park neighborhood, I became interested in photographing graffiti in Jersey City. About a half-mile from my apartment I happened upon a site nestled up against the Jersey Palisades beneath Christ Hospital:

If you look closely at the wall you’ll see ramps for a skate park. There are other features on the slab itself.

One day, sometime in the middle of October, 2007, I went by the spot to see if there was any new graffiti and saw that the floor slab had been demolished.

The DIY skate park was no more. A couple weeks later I saw a hand-lettered sign on the fence inviting passers-by to a meeting at City Hall to discuss ideas for a new park. While I had no particular interest in skate boarding – don’t do it myself, don’t have any children – I was curious: “Who at City Hall gives a damn about these kids”? I put on my banker’s suit, dark blue flannel with white pin strips, and showed up.

As I suspected, the meeting had been called by Steve Fulop, the young reform-minded Councilman who represented my neighborhood. Only four skate boarders showed up. That’s not enough, but the councilman said that, if they’d get more people to show up, he’d schedule another meeting. They promised; he put it on the schedule: Nov. 11, 2019. I offered to donate an annotated set of site photos to the Councilman and to the public library, which I did.

I’d guess there were 30 to 40 people at the meeting: teens, young adults, some older skate boarders, and a few parents. Fulop agreed to push for a new park to be built by the city. Where should it go? After some deliberation – I forget just how this happened, but I kept in touch with a number of skater boarders through email and they suggested a site beneath the thruway.

That’s a classic site for skate parks; many DIY parks have been built beneath thruways. One of the best known, in the country if not the world, is FDR, at the foot of Franklin Delano Roosevelt Park on the southern edge of Philadelphia.

Fulop got in touch with the New Jersey Turnpike Authority and got a favorable response. Meanwhile I had been thinking, and thinking. The spot chosen for the park, at Seventh Street and Newark Avenue, was only a couple of blocks from the Sixth Street Embankment, an abandoned railway structure six blocks long running East-to-West in downtown Jersey City. A group of citizens had been working hard to acquire the embankment from a developer – a complicated story, heartache, messy details, too much to slip in here – and turn it into and above-ground linear park – a bit like Manhattan’s High Line, which didn’t exist at the time.

I figured that, if we’re going to turn the embankment into a park, it would be easy to extend it over to Bergen Hill, pick up the skate park, go along the hill a quarter mile and then through the Bergen Arches, a mile-long man-made canyon running through the city. The Arches had once carried passenger trains from the Jersey Meadowlands to the Hudson River; but the tracks had been abandoned years ago and the canyon had become overgrown with lush vegetation. Why not connect it all into a two and a half mile linear park extending through Jersey City from the Hudson River to the Meadowlands?

I spit-balled the cost of such a project – a quarter to a half billion dollars (big bucks for Jersey City) – and spit-balled potential tourist revenue – perhaps $90 million a year – and wrote a report: “Jersey City: From a Skate Park to the World” [1]. I showed the report around, gave a copy to Fulop, and put it online. While I certainly didn’t think it was something the city could or would act on, I didn’t do it as a mere academic exercise either. I did it, well, as a way of indicating potential: This is something that could happen, somehow, someday, in this world. If only.

Meanwhile Fulop’s negotiations with the Turnpike Authority had fallen through. The skate park was dead. It was now early in 2008. A couple of years later I moved to Hoboken, immediately north of Jersey City, for a year and a half. Then I moved back to Jersey City in the summer of 2011. This time I moved into the Bergen-Lafayette neighborhood, one of the oldest neighborhoods in the city.

The skate park idea is rekindled

That’s when I discovered the DIY park that opened this piece. A bit later I discovered June Jones and the Morris Canal Community Development Corporation. June Jones had been born and raised in Jersey City and seemed to know everyone in Bergen-Lafayette. She founded Morris Canal CDC in 1999 and has run it ever since.

And in April of 2012 she decided to start a community garden; I volunteered to help: hauling dirt, pulling weeds, planting seedlings, and so forth – but also taking photographs, lots of them. At some point I learned that June had played a major role in convincing the city to turn a local brown-fields site into a city-wide park, Berry Lane Park. I suggested that they add a skate park to the plan. She was a bit skeptical, but took it under advisement.

Later in the year, on October 13, a local dance company, the Shua Group, staged performance at that DIY skate park.

If you look closely you’ll notice that the dresses seem kind of ‘frilly’. That’s because they’re made of latex gloves. The performance was called “Environmental Investigation”. To the left rear you can see a tower constructed of discarded plastic water bottles. Perhaps 30, 40, 50 people attended the performance along with a handful of skate-boarders and BMX bikers.

At about the same time one of the people involved in the community garden, a local contractor named Musaddiq, introduced me to Greg Edgell, who curated graffiti in a 15,000 square foot loft a quarter of a mile down Pacific Avenue from the community garden. He also ran late night dance parties in the loft and had established a boutique record label. I showed him that Skate Park report I’d written years ago – one aspect of it was that graffiti be made legal in the park. He thought it was a crazy idea, attractive, but it’ll never happen. I told him, you know, the world changes. We decided to work together.

By this time June Jones had decided that, yes, a skate park in Berry Lane would be a fine thing. She got our Councilwoman, Diane Coleman interested. We were all set.

I got in touch with Nick Orso, a skate park activist in Philadelphia, and Greg, Musaddiq, and I traveled to Philadelphia to meet with him on January 19, 2013. He took us to see the Mecca, FDR. It’s large, the length of a football field or more, though not nearly as wide, with dozens of features and, as you saw in the photograph above, covered with graffiti [3]. I’ve returned there year after year (my sister lives in South Philly, not far from FDR), and it is always under construction with new features being added.

Nick also showed us a smaller park, Pop’s Skatepark, in a different part of town. Pop’s was built with donated labor, as are many ‘legit’ skate parks.

Four months later Greg, Massaddiq, and I attended a meeting with Mike Yanetta, an active local skate boarder, Steve Leonardo, of NJ Skate Shops, Ben Delisle and Heather Kumer, of the Jersey City Redevelopment Agency (responsible for building the park), and Mark Vizini, a local contractor. We had a casual discussion about the specific needs, requirements, and capabilities of various potential vendors. Things seemed to be moving forward.

About two weeks after that meeting Councilman Steve Fulop was elected mayor over Jerramiah Healy. Fulop ran as a reform candidate while Healy ran with the Democratic establishment. In New Jersey politics tends to be Democratic machine politics. Very Old School.

Meanwhile, the local skate boarders were not waiting for the City to construct this park, the one that didn’t happen back in 2007-2008. Here you see two of them constructing a new bump at the Morris Canal DIY park. That’s Mike Yanetta on the right.

A year later, in April 2104, Site Design held a design charrett in the basement of the Fountain of Salvation Church on Communipaw Ave., a few blocks from the site of the Berry Lane Park. I’d estimate that there were thirty people seated around a half dozen tables: skate boarders (Yanetta and Leonardo among them), neighborhood organizers (e.g. June Jones and associates), and others from the neighborhood. Each table was asked to design their ideal park.

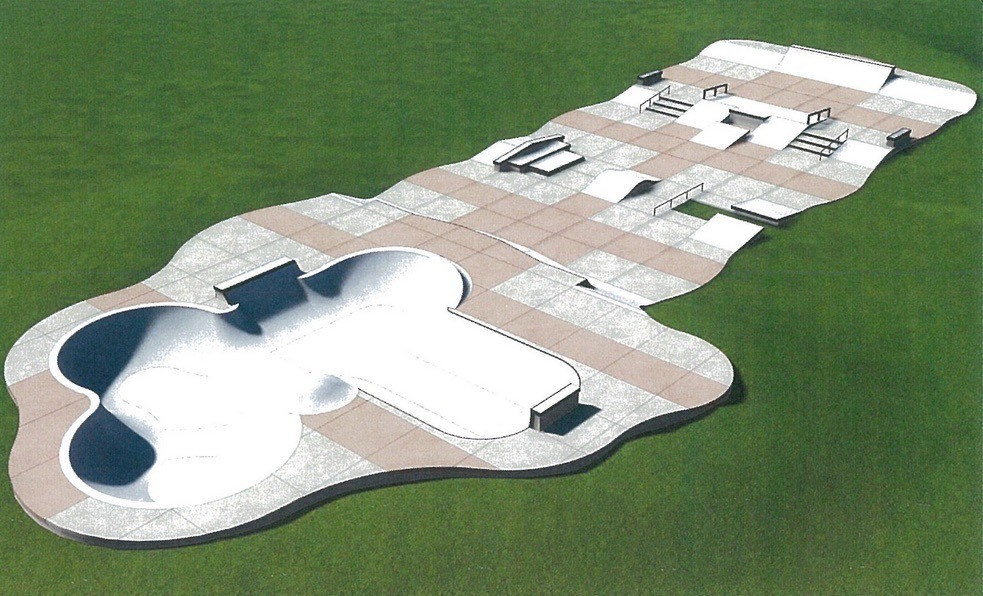

Site Design took those suggestions and came up with this design:

The design incorporates two distinct styles of skate boarding. The bowl at the left descends from 1970s skating in California, which sometimes took place in drained swimming pools, while the area at the right is based on street skating. Free-style street skating had been around since the beginning in the 1940s and 50s but had picked up in the 1980s and then became dominant in the 1990s.

Here’s the location where the skate park was to be built, roughly at the pile of dirt in front of the silos.

Early in 2015 the City applied to the Tony Hawk Foundation for a grant toward the construction of the skate park. Hawk is a legendary skate boarder; the purpose of his foundation is to fund underserved communities. And, with a population over a quarter of a million and only one skate park, a small one using portable wooden features (plus, of course, those don’t look don’t tell DIY parks), Jersey City was certainly underserved.

On March 4, 2015, the Tony Hawk Foundation announced that it had awarded Jersey City a $25,000 grant. Hooray for the good guys! But it’s better than that. For the grant came with a time limit. If the City didn’t build the park, it would loose the grant. And that would be embarrassing for the back room boys and gals.

Berry Lane Park is opened, then the skate park

On June 6, 2016, Berry Lane Park had its grand opening. Without a skate park. The money had yet to be scrounged up.

Sometime later in 2016, I don’t know just when, we had another meeting with city officials, a meeting Greg and I refer to as the “bake sale meeting”. The City had come within an inch, one little inch, of funding the construction of the park when, wham! something else assumed priority and the funding disappeared. Did we have any ideas? Well none of us were millionaires, nor did we know any, so no, we don’t have any ideas. Surely you don’t think we’re going to fund this half-million dollar park with a thousand bake sales, do you?

That’s a bit unfair I suppose. It wasn’t their fault – the officials in the room. It certainly wasn’t our fault. Nor do I recall just what was said. I’m only giving a flavor. It wasn’t anyone’s fault. It never is.

Politicians.

Kismet.

But four years and who knows how many smoke-filled back-room meetings later, Kismet came through. Tsivikos Construction broke ground in October, 2019, started pouring concrete in March, 2020, and the park was opened on August 6, 2020.

Notice the adult skater and the child in the next photograph. That’s how it is at skate parks. Skate boarding is an individual sport. People of all ages and all skill levels will be in a park at any one time. There’s no one there to schedule times or referee disputes. There are no rules – well there are at Berry Lane. They’re listed somewhere. They boil down to this: don’t be stupid, no drugs and alcohol, live and let live, don’t create a mess, be kind and courteous. Civilized rules for people of good will.

What Happened? Lessons Learned

First Lesson: No one planned it this way. But it happened. I don’t know what Councilman Fulop had in mind when he called the original meeting in November of 2007, but whatever it was, it didn’t happen. I know that when I came out of the second meeting I was excited about seeing local activism and democracy in action. What a good lesson for the kids, I thought. Whatever they took away from the experience, that lesson wasn’t it.

As for me, sure, I was disappointed. But the library had a record of that original DIY park. And I had that crazy-ass report, Jersey City: From a Skate Park to the World. That report gave me a stake in the city of a kind I hadn’t had before. That framed my subsequent experience in the city.

I took notes, kept a record, got people interested, and they did the rest.

Second Lesson: Trust and good will are necessary in the political process. This process revolved around three groups of people: 1) the anarcho-libertarian culture of skate boarding, 2) grass roots community activism and organization, and, 3) old school machine politics.

Those are very different modes of social interaction and organization. Skate board culture is fluid and can survive anywhere. But its capacity for scaling up is limited. You can’t pile water on water. It took grass roots organization to give the skate boarders a home and to build this desire and hope into something solid enough to attract the attention of professional politicians. And they, they came up with the money, in their own sweet time.

At each step of the way people had to trust one another, even if things didn’t work out. It is because trust was there that will was able to find a way.

Life moves on. Always.

References

[1] William Benzon, Jersey City: From a Skate Park to the World, Scribd, July 28, 2013, https://www.scribd.com/document/58300722/Jersey-City-From-a-Skate-Park-to-the-World. Here’s the report’s executive summary:

Jersey City has an unparalleled opportunity for developing park space and cultural amenities in a two-mile corridor running from the Powerhouse Arts District in the East, along the Sixth Street Embankment to the Palisades, then up the River Line to the Bergen Tunnel, and west through the Erie Cut-Bergen Arches to JFK Boulevard. What is unique about this strategy is that is builds on both abandoned railroad properties and on Jersey City’s status as a center for graffiti art of the highest caliber. By capitalizing on its graffiti heritage, Jersey City can attract tourists from around the world and establish itself as an international center of cutting-edge art.

This development strategy includes three park-garden areas: 1) Sixth Street Embankment, 2) River Line Walk, and 3) Erie Cut. A skate park is already being planned for the River Line Walk area. At full development the Erie Cut would have a series of small gardens in various national styles – Indian, Chinese, Spanish, etc. – and a conservatory linking the bottom of the cut to the street-level surface(Route 139). There would also be two modest museum complexes: 1) a graffiti museum at 12th and Monmouth, and 2) a railroad museum nearby at the Bergen Tunnel. These complexes would include restaurants and shops.

A thumbnail calculation indicates that these developments could bring new tourist revenue to the city in the amount $36 to $90 million (or more) annually. Other benefits include increased property values along the corridor and new businesses.

[2] Environmental Investigation: Shua Group, New Savanna blog, October 14, http://new-savanna.blogspot.com/2012/10/environmental-investigation-shua-group.html.

[3] On FDR, see Matthew Ward, Skate Parks and Skateboarders, Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia, https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/archive/skate-parks-and-skateboarders/.

See also, William Benzon, Is FDR the capital of the SK8board nation? 3 Quarks Daily, Jan. 7, 2019, https://3quarksdaily.com/3quarksdaily/2019/01/is-fdr-the-capital-of-the-sk8board-nation.html.