by Andrea Scrima

Part I of this is here.

#4: OWWW

Pain is a private experience that happens within an individual body; it is internal and essentially invisible. As much as we might commiserate, we cannot “share” another’s pain; we can merely witness the behavior it induces, inquire into the nature of the pain, and try to help alleviate it.

A medical diagnosis depends on a precise description. Is the pain aching, searing, shooting? Does it prick, stab, sting, or throb—or does it gnaw, tingle, cramp, burn? Is it sharp or dull? Asked to evaluate the intensity of their pain on a scale of one to ten, patients often find themselves at a loss. It hurts, they say. It’s unbearable. Pain is one of the least communicable human experiences.

Pain is also a weapon: power is asserted through violence, in other words, through causing pain. War’s objective is to shoot, burn, blast, and otherwise annihilate human flesh and to damage or destroy objects human beings regard as extensions of themselves: their homes, their possessions, photographs of loved ones, the buildings they live in, their religious and cultural institutions—and often entire cities, along with the history preserved in their architecture, in their libraries, museums, archives. War aims to not merely seize territory and take control, but to induce pain—and to make that pain visible to demoralize its victims, rob them of their voice, their individuality, their humanity.

Foucault described the process whereby the public execution—historically staged as entertainment for the masses—gradually became obsolete. In the practice of extrajudicial torture, however, the spectacle lives on. While the interrogation-induced confession is presented as torture’s justification, incriminating information obtained under duress is generally deemed unreliable or worthless. The infliction of pain serves a different purpose: torture becomes a ceremony, a form of clandestine theater where coercion and admission of guilt merge in a ritual whose power is rooted in secrecy.

For the victim, pain is multiplied until it leaks out of the tortured body and transforms the world into an externalized map of the individual’s suffering. Elaine Scarry writes that “intense pain is also language-destroying: as the content of one’s world disintegrates, so the content of one’s language disintegrates; as the self disintegrates, so that which would express and project the self is robbed of its source and its subject.” To witness the infliction of pain is often psychologically unbearable—yet overexposure inevitably leads to desensitization, indifference, or even a detached curiosity.

#5: EWWW

Disgust is a visceral sensation; when something makes us nauseous—spoiled food, bodily fluids or excrement, an unexpected act of violence—we feel sick, compelled to vomit, to prophylactically expel the offending substance from our bodies. In evolutionary terms, disgust is thought to have developed as a physiological reflex to protect the organism against the dangers of disease and contamination. We gag at the sight of things that disgust us, are overcome with revulsion; we recoil from them, physically distance ourselves, take care not to touch the odious, rotten, infectious thing.

The word “disgust” is also used in reference to people or situations considered morally unclean or mendacious. But is this the same thing? When a person is suspected of deception, disloyalty, or hypocrisy, it’s said that something about them “smells fishy,” something “stinks.” Yet a feeling of repugnance can also occur when an imagined purity of some kind—whether racial, sexual, or ideological—is perceived as having been violated. Moral disgust, then—unlike the universally human bodily response—is a socially conditioned emotion, and as such, unreliable. It operates on instinct and is thus its own tautological justification; it passes judgment on and condemns the other.

An attribute of moral disgust is that it induces us to pull back from the offending situation or person; as opposed to anger, which triggers an aggressive reaction, disgust sets off a pattern of withdrawal and avoidance. When we’re disgusted, we recoil, turn up our noses as though at an offensive odor; we frown, avert our eyes, edge away. Situated on a continuum with disgust is contempt, which is felt when someone or something is perceived as immoral or unethical or fails to conform to an interpersonal standard we adhere to. Although a cultural construct, contempt also functions as a reflex; when translated into social or political agitation, it can be dangerous.

Jean-Paul Sartre’s Nausea chronicled a state of malaise, a disgust with the self and the world, an existential descent into nihilism. What inspires nausea today, elicits our disgust? And what do we do when the sources of disgust multiply—how do we interact with the world when disgust overwhelms us, when it transforms into moral horror? There is a point of oversaturation when boundaries blur and the self is indistinguishable from the things that cause it revulsion: when disgust and contempt turn inward and become internalized, when the self absorbs and transforms them into shame and guilt; when it understands, with unmistakable clarity, that it is capable of the very things it so reviles.

#7: AWWW

I look at you and offer an encouraging smile: it’s an awkward moment. You tell me of your suffering and I feign compassion. I feel my face subtly shift as it transforms into its own mask: eyes slightly widened, brow furrowed, I gaze back at you in simulated empathy. Seated opposite me, you are stripped bare; you expose your weakness. Then something in you collects itself, grows cautious, alert suddenly to the spectacle of your unprotected state and your own vulnerable self and my detached vantage as I coolly view you. You excuse yourself, embarrassed; I assure you that there is no need for apologies.

We praise people for enduring their pain in silence; admiringly, we say that they never complain. But do we consider their loneliness as they spare us the obligation of expressing sympathy, of imagining ourselves in their place? Surely we wish no harm; surely our response is sincere: we would do anything to alleviate their suffering, or so we believe. We think of Schadenfreude as a despicable character trait. We wince at the sight of physical injury, wither inside at the display of the self unraveled, unable to maintain its composure, its dignity and pride. But we are also curious, absorbed by an almost scientific interest. Finally, we give in to our fascination—so these are the symptoms of a body as it breaks down; these are the utterances of a mind as it falls apart. Safe in our perch of good health, we observe the soul in all its nakedness as it watches its future shrink before it, dissolve into the vanishing point of an unknown horizon.

Pity has little to do with compassion; it derives from the superiority we feel in a secure position, and as such, it is a luxury. Pity masquerades—chiefly to ourselves—the power we feel towards those in a weakened state. We feel pity when viewing the poached body of a wild beast no longer able to tear us to shreds; we’re free now to marvel at its nobility, its beauty. Pity is an indulgence we allow ourselves once a threat has been neutralized. We pity the pretty and vain when their good looks abandon them; we shed tears for the competition when they lose: it is the gladiator’s magnanimity toward a conquered opponent. Pity, however, lacks true empathy; it is the cousin of sentimentality. The former predator is reconfigured, for instance, in the child’s stuffed animal—with a ribbon around its neck and an adorable shirt that doesn’t quite cover its belly, the cuddly toy is the exemplar of sentimental kitsch—and in spite of the very real tears we shed, sentimentality, as Oscar Wilde famously quipped, is the “bank holiday of cynicism.”

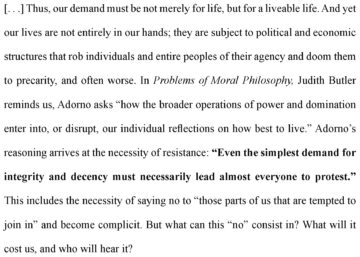

For the past ten years, Andrea Scrima has been working on a group of drawings entitled LOOPY LOONIES. The result is a visual vocabulary of splats, speech bubbles, animated letters, and other anthropomorphized figures that take contemporary comic and cartoon images and the violence imbedded in them as their point of departure.

Against the backdrop of world political events of the past several years—war, pandemic, the ever-widening divisions in society—the drawings spell out words such as NO (an expression of dissent), EWWW (an expression of disgust), OWWW (an expression of pain), or EEEK (an expression of fear). The morally critical aspects of Scrima’s literary work take a new turn in her art and vice versa: a loss of words is countered first with visual and then with linguistic means. Out of this encounter, a series of texts ensued that explore topics such as the abuse of language, the difference between compassion and empathy, and the nature of moral contempt and disgust.

From May to the end of August 2024, several work groups from the LOOPY LOONIES series are on view at Kunsthaus Graz, Museum Joanneum, Austria, accompanied by postcards containing excerpts from these texts. Scrima read from these texts in a lecture/performance on May 15, 2024.

The first part of this overview of the LOOPY LOONIES project was published June 3 here at 3 Quarks Daily.