by Thomas O’Dwyer

A statue of Canada’s first prime minister, Sir John MacDonald, has become the latest lump of kitsch concrete to hit the ground after protesters pulled it from a plinth in Montreal and cheered as the head broke off and bounced across the pavement. (MacDonald was linked to vicious policies that killed and displaced thousands of indigenous people in the late 19th century. His system forcibly removed at least 150,000 children from their homes and sent them to often abusive state boarding schools). That’s as good a reason as any to add this to the list of monuments being dethroned around the world.

Another good reason is that phrase “lump of kitsch.” Jonathan Jones recently lamented in The Guardian that the falling statues were being followed by a sterile conversation about who does and doesn’t “deserve” a statue. “This is because all statues are dumb. They cannot represent big or complex themes. All they can do is function as crude symbols. They reduce history to celebrity culture. So many Victorian statues survive in our cities because 19th-century historians believed ‘great men’ and their leadership created history,” Johnson wrote, adding that every dumbass general who ever won an obscure skirmish had a statue somewhere across the British empire. No heroic soldier ever did.

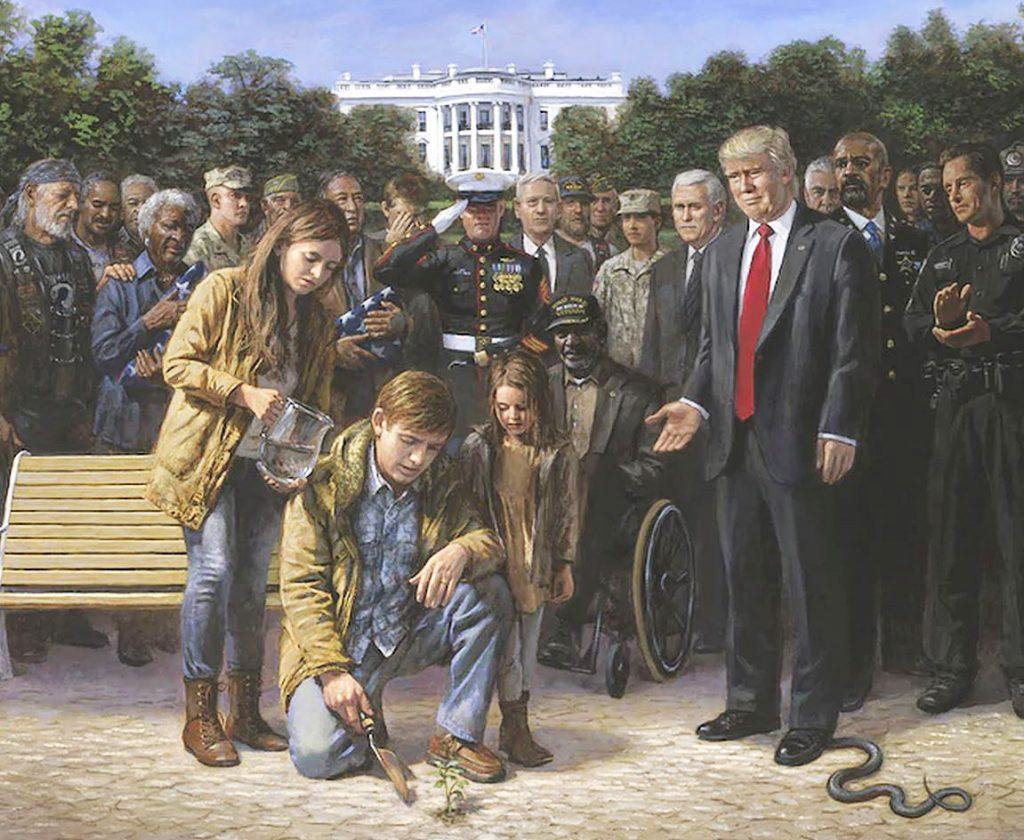

So, what a lineup of dumb statues one could craft from that display of Trump royalty at the recent Republican National Convention. The “great man” being honoured this time was “the bodyguard of Western civilization,” as Charlie Kirk, founder of the anti-liberal Turning Point USA, described the president. This, wrote The Washington Post, was “an image in keeping with painter John McNaughton’s kitsch paintings of Trump.”

McNaughton, a former hawker of treacly landscapes, is now America’s most famous pro-Trump, mass-market painter of this century. And once again, apropos the Trump era, we come across the K word: “The first night of the GOP convention was, inevitably, a cocktail of kitsch spiked with dystopian fiction, an outsize slice of American cheese served up to a president in desperate need of comfort food,” wrote Post columnist Alyssa Rosenberg. Yes, it was all there in a tableau of Disney Americana, forests of flags, waving feminine hair, buttoned-down ole boys, Nikki Haley’s shocking-pink suit. Shiny artistic conservatism will put to flight the dreary grey and darker colours of those uppity Biden Marxist socialists and anarchists.

Kitsch is a shifty term, slippery as a cute ceramic kitten, with more definitions than Merriam-Webster. Most people avoid defining it, preferring to adapt Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart’s comment about pornography – “I know it when I see it.” I see you, pale white Jesus with the flowing girl-hair, blue eyes, red cape and botched open-heart surgery. The Catholic church may have sponsored some soaring great art over its long history, but the kitsch, my god, the kitsch! Allen Ginsberg wrote that Andy Warhol’s “entire private moral reference was to the supreme kitsch of the Catholic church.” The holy tackiness, the provincial tastelessness, the velvet virgin Barbies, all packed into rows of Campbell’s soup cans. A luminous Thomas Kinkade landscape is almost a blessing by comparison, even if it lacks a glowing Jesus standing on a rustic river bridge.

We could just laugh at it all but that takes kitsch too seriously. Besides, we also have camp, kitsch’s less-evil twin. Kitsch is dumb like a showy computer; camp is self-aware, artificial art. Camp can be golden, kitsch is merely gilded. Kitsch is the opposite of simplicity, the antithesis of minimalism. The world seems as awash with kitsch objects as the oceans are with other human junk, and indeed the invention of cheap plastics has been responsible for both. Knick-knacks, tchotchkes, rustic doodahs, tourist souvenirs, lava lamps, African masks, ceramic owls:

All things counter, original, spare, strange;

Whatever is fickle, freckled, who knows how?” [Gerard Manley Hopkins]

The literary equivalent of kitsch would be an essay riddled with corporate cliches. In the 1930s, the art critic Clement Greenberg wrote in an influential essay, Avant-Garde and Kitsch, that “the main trouble with avant-garde art and literature, from the point of view of fascists and Stalinists, is not that they are too critical, but that they are too ‘innocent,’ that it is too difficult to inject effective propaganda. Therefore kitsch is more pliable.” Greenberg underlined his point by adding the example of a peasant who has no time or possibility to “condition” himself into liking Picasso. The peasant will go back to kitsch because he can “enjoy kitsch without effort.” I once overheard an English tourist couple in Pakistan discussing why the local trucks and buses were decorated so colourfully and elaborately inside and out. “It’s because they are unsophisticated, like children,” the husband mansplained to his wife. “They like bright colours and shiny things and garish displays.”

It was an eerie echo of the Greenberg essay about peasants hating Picasso, and yet the sneering English couple were so typical in their lowbrow middle-class snobbery that I was prepared to bet they had a print of the supreme kitsch Chinese Girl, by Russian emigree Vladimir Tretchikoff, hanging in their London flat in a gold frame. However, although art lovers have always derided it as the epitome of kitsch, this painting, popularly known as The Green Lady, fetched $1.2 million in auction in 2013. Be careful what you call kitsch – it can come back to haunt you as true art. A piece of kitsch can be like a drawing which contains a deliberate optical illusion that suddenly reverses its meaning as you look at it – a tall cat becomes a woman brushing her hair or a vase of flowers. Did that ridiculous Marcel Duchamp inverted urinal just flip into a classic work of art called Fountain?

It was Greenberg who brought the word kitsch into common usage. He wrote that kitsch is a “semblance of genuine culture … mechanical and operating by formulas, the epitome of all that is spurious in the life of our times.” It was a symptom of a bourgeoisie trying to form an “instant cultural identity” while avoiding any difficulty. It inevitably was linked to capitalism in an attempt to purchase aesthetic experience, commodifying art with no regard for quality or discernment. Greenberg noted that kitsch emerged from the Industrial Revolution in a capitalist commodity market where profit demolishes aesthetics. He cited as an example the magnificent 18th-century French Hôtel de Varengeville. The mansion had ostentatious furniture, excessive gilding, and ridiculous displays of wealth. This suggests kitsch, said Greenberg, but it isn’t. The hotel was a product of 18th-century aristocratic culture, not industrial capitalism, hence it was not kitsch. But if someone reproduced a room from Hôtel de Varengeville in their suburban modern home, that would be kitsch.

Critics scoffed at Neuschwanstein Castle in Germany as the “king of architectural kitsch” when it was completed in 1892. Now 1.5 million tourists a year flock to bask in its faux Wagnerian Gothic grandeur and to marvel how it looks like a modern monument of kitsch, the Cinderella Castle in Disney World, which indeed is based on it. The late American painter Andrew Wyeth generated the kitsch-art illusion par excellence. As craft, Wyeth’s landscapes were technically excellent, but his work was mostly dismissed as sentimental, formulaic, illustrative, tired or “sweet.” Yet it is telling that when the art historian Robert Rosenblum was asked to name “the most overrated and underrated” artists of the 20th century, he offered only one name for both categories – Andrew Wyeth.

In Europe, an important Norwegian painter, Odd Nerdrum, has confronted the dilemma head-on. (If a novelist chose the name Odd Nerdrum for a dissident art character, would that be too kitschy?) Nerdrum not only declared himself to be a kitsch-painter who identifies with kitsch rather than with the contemporary art scene but in 1998 he also founded the Kitsch Movement, an international grouping of classical painters. Since Nerdrum is a serious and talented painter, critics at first thought his declaration was a joke or PR tactic. But as he published more articles and books on the subject, Nerdrum’s position became an implied criticism of contemporary art. He has argued that western art is scarcely 250 years old and that kitsch is a valid opposite, representing the values that modern art has thrown away. Within ten years the Kitsch Movement had become so seriously regarded that it collaborated with the Florence Academy in 2009 to organise a biennale travelling exhibition, “Immortal Works,” that included painters from around the world.

Nerdrum’s movement promotes the techniques of Europe’s Old Masters including narrative, romanticism, and exotic imagery, aligning itself with the arts of ancient Greece and Rome. For its members, kitsch is a positive concept, not at all opposed to the evolution of modern art, but with its own independent craft structure. The painters say theirs is not an art movement, but a philosophical one, separate from art. In Nerdrum’s interpretation, Kitsch is a contemporary descendant of Gothic, Rococo and Baroque. He is not excusing what most of us call kitsch – artistically worthless, tasteless, manipulative garbage pretending to be significant. By that definition, “art-as-theory-as-art” is also kitschy and perpetuated by a cabal of self-selected pretentious snobs who are often too cowardly to call out a pretentious can of shit for the artistic crap it is.

Art ideologists and their academic enablers are invariably little-talented themselves and cast their nets of “not-art” too indiscriminately, fooling art lovers into thinking that all modern figurative art is now kitsch. Nerdrum himself is a technically talented and highly regarded popular artist and rejects the idea that figurative-abstract concepts have anything to do with a painting’s modernity or antiquity. Whatever faddish theorists say, Kitsch Movement artists assert that while history will be the final judge, “the public will always value a Tiepolo or a Titian over a Warhol, or a Hirst in the long run.” Delacroix also thought so when he asserted that art is about “greatness of resonance and wonderment,” about drawing the viewer to admire and marvel.

Musicians have suffered from confusion about art and kitsch as much, if not more than, painters, sculptors and architects. For the culturally nervous postmodern art buff, the standard warning signs that kitsch may be present are sentiment, simplicity, imitation and sweetness. “The objects or themes depicted by kitsch are instantly and effortlessly identifiable,” wrote the Czech author Tomáš Kulka. Never mind the foot-tapping infectious joy of Abba’s songs. Kitsch! But wait, there’s more – the symphonies of Gustav Mahler and Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky have also been said to bear these marks of Cain-kitsch. More than one critic has denounced Mahler’s 6th symphony as a monstrous work spawned in kitsch hell – not grand but grandiose, peppered with homages to other works, and dripping with teary emotions of hope, longing, tragedy, everything but musical furry kittens.

Composer Richard Strauss famously described his own work as kitsch: “Must one become seventy years old to recognize that one’s greatest strength lies in creating kitsch?” he wrote in a letter to a friend in 1934. Tchaikovsky was called a “kitsch of genius,” and the Finnish Jean Sibelius was so disturbed by accusations of using kitschy folk and nationalist themes that he made an ill-advised attempt to switch to modernist disharmony. Still, many believe that Strauss was being humorous about kitsch to taunt those who wanted to see romanticism dead. He knew his technical skills were so good that he would be recognized for the skills alone – and he knew his modernist detractors could not match his technical level. He could afford to play with kitsch; he had enough real currency in the artistic bank.

So, kitsch is annoying, unimportant, tawdry, sleazy and everywhere. So are cockroaches, and we identify and avoid them. But there is a dark side. In the Danish political drama series Borgen, coalition politicians are discussing visual themes for their election campaign. One turns to Svend Åge, leader of the extreme-right Freedom Party and says, “Well, it’s easy for you – same old theme, flying flags and waving fields of wheat.” Authoritarian kitsch – they love it on both ends of the spectrum. Flags, anthems, happy peasants in fields of corn, happy high-haired housewives in the kitchen. Milan Kundera made authoritarian kitsch a theme in his novel The Unbearable Lightness of Being. According to the narrator, kitsch is “the aesthetic ideal of all politicians and all political parties and movements.” However, where a society is dominated by a single political movement, the result is “totalitarian kitsch”:

“When I say ‘totalitarian,’ what I mean is that everything that infringes on kitsch must be banished for life: every display of individualism (because a deviation from the collective is a spit in the eye of the smiling brotherhood); every doubt (because anyone who starts doubting details will end by doubting life itself); all irony (because in the realm of kitsch everything must be taken quite seriously).”

The Nazi regime is usually pointed to as the ultimate rotten system build on totalitarian kitsch philosophies that led to unbridled mass slaughter. So, it is startling to find that on 19 May 1933, Nazi Propaganda Minister Josef Goebbels passed an anti-kitsch law, one of the first enactments of the new government, “A Law for the Protection of National Symbols.” It was immediately known universally as the Anti-Kitsch-Gesetz. It did not define kitsch, but the legislation listed in minute detail the “small household atrocities” to be avoided in using symbols of the state like swastikas, icons, images of Hitler and his ministers, in ways that would “damage civilization or the Volk (people).” National symbols were not to be used on toilet paper, cute plastic kittens or garden gnomes and the Führer’s head was not to be used to top pencils. Embroidered cushions showing Hitler feeding a deer were verboten. In other words, it became criminal to use the official kitsch produced by the Nazi regime in any kitschy ways, even if well-intentioned.

Nazism’s fascination with ritual and formulaic repetition underpinned its fetishism of beauty, purity, mythology, and its fantasy of a thousand-year Reich with Valkyries riding through the skies. The classical and national myths fuelled nostalgia for warriors of old, the glory of military victories, the sacrifices and genocides that underpinned the idea of the Aryan nation. Nazi kitsch hung like a painted curtain or stage-set across the nation to give the Volk a fake inspiring panorama. Its real purpose was to hide the reality of blood and atrocity that went on behind it. Kitsch is harmless until the authoritarians parade under it. Then it isn’t.