by Andrea Scrima

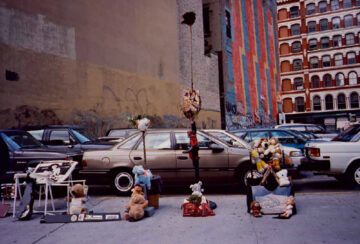

I recognized the corner immediately: it was right next to Cooper Union, on Lafayette Street in downtown Manhattan. There used to be a large parking lot on the other side of the street, where passers-by occasionally happened upon a colorful bricolage cobbled together from stuffed animals and clothes, discarded household items, deformed umbrellas, and battered car parts. These strange and playful conglomerations looked as though the bric-a-brac and refuse had been plucked together by some invisible furious force to house a spirit or daemon. They were, of course, carefully composed works by the late African-American artist Curtis Cuffie, one of the many ephemeral assemblages he created in the streets of downtown New York in the 1980s and 1990s.

Cuffie installed his improvised ensembles of found objects on fences, window grilles, sidewalks, and traffic signs in Cooper Square, the Bowery, and elsewhere; they were always temporary, and only a few of his works have survived. Cuffie periodically lived on the streets around Cooper Square and his homelessness must have made his emotional tie to the treasures he found and wheeled around in shopping carts all the more urgent. Most of the works he created from this repertoire of materials were abstract, shrines that seemed to grow out of the flotsam and jetsam of a city in constant transformation; seen from a passing car, they flashed in the sideview mirror like otherworldly apparitions. But there were also figurative sculptures: ragged garments strung on wire and string and adorned with hats or wigs became animated spirits on a secret mission. Today, the few remaining works by Cuffie that were not taken down and destroyed by the police or street cleaners are shown and sold in the pristine white spaces of uptown Manhattan galleries, stripped of their context and also, perhaps, a good deal of their meaning.

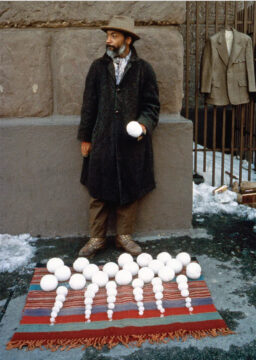

Back then, many artists responded to the grim streets of downtown New York with temporary interventions and sculptures improvised from found materials. Some of them, most famously David Hammons, also staged performances. One freezing February afternoon, Hammons stood on the southeast corner of Cooper Square and Astor Place, where other street vendors were selling LPs and used paperbacks, and presented a battery of snowballs arranged according to size. That was in 1983, a year before I moved to Berlin as a young art school graduate. Like many of Hammons’s ironic actions, it was a canny commentary on the commercial art world. Initially well beneath the radar of the art establishment and later as a celebrated conceptual artist, Hammons camouflaged himself in the urban clichés about African Americans prevailing at the time—street hustler, drug dealer, criminal, homeless person—and in doing so underscored their precarious situation on the fringes of white society. I lived a few avenues east of Cooper Union and remember the day I happened upon Hammons’s snowballs. The scramble for success was well underway in the East Village art scene, and I was already feeling a resistance growing inside me against the gallery system and art’s commodification. I stopped, baffled, but was still too naïve to fully understand the full dimensions of Hammons’s brilliant gesture. His protégé Cuffie began his installations a few years after I left New York, and I missed out on them entirely. Four decades later, in the spring of 2024, the Grazer Kunstverein darkened its space to present an exhibition of over 700 projected slides of these elegant, humorous, spare, extravagantly sad ensembles, and I discovered his work for the first time. It was like a puzzle piece that had long been missing.

It goes without saying that Curtis Cuffie’s works were created outside the art system and quite likely from inner necessity. On the streets, in the throes of the New York rat race, Cuffie conjured up unexpected oases that invited people to stop in their tracks and marvel at the beauty and absurdity of it all. Dented trumpets and snake-like plastic tubes framed the occasional gem—a clock, a doll, a painting, an African mask—and offered a kind of freedom, a protective space to think and breathe. Born in South Carolina, Cuffie moved to New York at the age of fifteen. He was only 47 when he died. Even if the alternative world his works promised never really came to fruition for him, they continue to propose a different kind of being in the world—a blueprint for how to home in on our perception of ourselves in space and time and experience the present moment, the startling fact of existence.

~

Can art make the world a better place? I don’t know, I replied. I was preparing an exhibition for the Kunsthaus Graz—and so of course I believe in art, and of course it’s essential to my own and the world’s survival—but I hesitated. I’d been asked to meet with an international group of students visiting Graz, and they’d come to the Rose Garden atop the Schlossberg to ask the city’s writer-in-residence (me) questions about art’s importance to society. Evidently, they were expecting a more hopeful answer. I don’t know anymore, I continued, if art can change anything in the face of the catastrophes coming our way. I’ve come to take a modest position on whether or not art can wield any real social or political power—particularly now, in our media-driven cultural economy. We stood for a few moments in silence as the students absorbed my response.

It’s important to interject the fundamental fact that the educational value of art has been put to the test many times. When you encourage young people to take art seriously and to think about it, really think about it—and if you give them the freedom to be creative themselves—it trains their critical skills and sharpens their perception. Studies have demonstrated that engaging with art enhances the brain’s neuroplasticity and improves both psychological resilience and the ability to intuit abstract and cross-disciplinary connections, for instance in math and physics. Art makes us flexible, versatile, and tolerant; it turns us into observers well-versed in thinking outside the box. Schools that cut back on art, music, drama, and literature eventually grapple with lower grade-point averages—including in the natural sciences. Let that sink in for a moment. As Christopher Tyler, former director of the Smith-Kettlewell Brain Imaging Center, said: “art accesses some of the most advanced processes of human intuitive analysis and expressivity.”

So why has art lost its power, one of the students wanted to know. But has it? Dictators are terrified of art, I said; why else would they lock up their artists and writers, forbid them from speaking out? Why else would they imprison and kill them? They’re well aware that art gets at the heart of things, strikes a chord in people’s hearts, exerts a profound and mysterious effect. They understand the danger all too well: it connects people on a deeper level, gives them a common purpose, fosters courage. Maybe the more accurate question is why art has lost its power in the West—and how we can find our way back to an art that’s capable of expressing our most urgent truths. The question, in other words, is: How can art become dangerous again?

~

Biology determines human behavior—we’ve heard it again and again, the whole unsavory lot of it: the dog-eat-dog world and the subjugation of women; the inevitability of capitalism. That nature has designed it so that Earth’s creatures have little choice but to compete for resources, that human instincts and emotions primarily serve the purpose of reproduction. From Darwin to Dawkins, it’s about using violence to eliminate your rivals and secure the optimal breeding ground for your own genes. It’s a matter of eat or be eaten: because it’s not the pursuit of a just society, but biology that determines the political order, gender relations, and the economy. And biology is cruel, predatory, and entirely indifferent to moral values and even civilization itself.

The neoliberal market economy, based on the neo-Darwinist evolutionary model, ensures that the process of “natural” selection functions seamlessly: people are sifted out according to their productivity and profitability, while capitalism is justified as the paradigm closest not only to human nature, but to all life on Earth. The Cambrian period and its explosive spread of diverse life forms over 55.5 million years—from multicellular organisms to animals with spines, sharp teeth, and hard skeletons and shells—represents the primal conditions of life on Earth as a struggle for survival. But evolutionary theorists leave out the fact that life formed much earlier, in the Ediacaran period, named after the Ediacaran Hills in South Australia, where fossils several million years older than the Cambrian were found. The creatures of this era existed in an ecology of mutual interdependence; underwater organisms that were neither plant nor animal lived in peaceful symbiosis and nourished themselves through the non-predatory processes of photosynthesis, chemosymbiosis, and osmotrophy. 92 Million Years of Collectivism, a film by artist Jonas Staal featured in the exhibition “Other” on view earlier this year at Kunsthaus Graz, inspires viewers to think about the more cooperative and sustainable social systems of our evolutionary past. According to Staal, this era, which lasted 92 million years and thus almost twice as long as the Cambrian, should be considered the truer model for the origins of life on this planet—a life based on cooperation and coexistence. Yet it comes as no surprise that we’ve projected our own Western economic model onto nature: in a “geo-revisionism” that defines capitalism as a natural and even primordial state, we’ve declared the narrative of the predator-prey relationship to be life’s blueprint. Staal calls upon us to reconsider this myth in order to prepare the way for establishing an alternative model not as a paradisiacal “Garden of the Ediacaran” outside of time, but as a workable future perspective for an endangered planet.

~

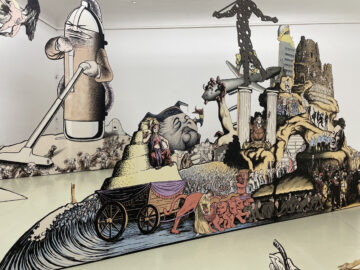

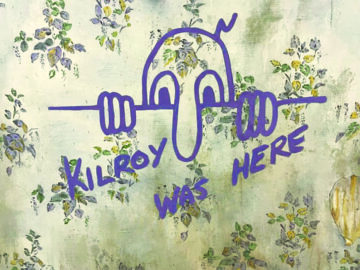

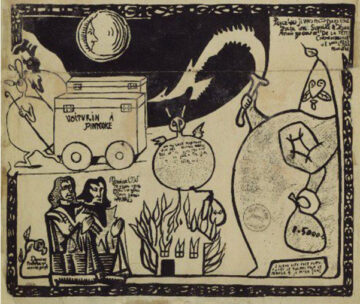

In the fall of 2023, hoping to distract myself from the terrible news, I visited a two-part exhibition at the Halle für Kunst and the Neue Galerie Graz to see the exhibition “Ridiculously Yours!” The show brought together a wide range of positions that employ exaggeration, silliness, camp, and mockery as artistic strategies. Satire is as old as art itself; absurdity and nonsense are excellent ways to stand up to power, while laughter remains a potent weapon for challenging political oppression and abuse. In a large-scale installation by the artist Jim Shaw, painted cut-outs filled the space in the form of nested backdrops depicting episodes in history in a cartoon-like style. The mood of the work is apocalyptic, as elements from Picasso’s Guernica and Salvador Dalí’s Soft Construction with Boiled Beans (Premonition of Civil War) merge with caricatures of more recent villains like Richard Nixon. In a cross between political allegory and private nightmare, an anthropomorphic vacuum cleaner sucks up rows of small, frightened businessmen, while a gigantic locust climbs a skyscraper like a King Kong about to announce a new plague. Below them, a procession moves silently through the centuries, a “Where’s Waldo”-like picture in which mercenaries from antiquity morph into medieval monks and finally into armies of soldiers wearing gas masks. I’ll admit, none of this sounds particularly funny—but as always, my attention was drawn to an inconspicuous detail: “Kilroy was here,” the famous graffito of a bald, big-nosed figure peeking over a wall that American soldiers drew everywhere during World War II to mark their presence and their survival on the war’s remotest fronts.

Shaw’s dark humor reminded me of the late opposition politician Alexei Navalny, whose political strategy was to poke fun at Putin and make him look small and paranoid. Dictators fear nothing more than being ridiculed—and indeed, Navalny’s messages and videos were subversively funny, and they spread like wildfire, just as the fictional underdog Kilroy once traveled across thousands of miles of Allied trenches. Some weeks after Navalny’s death in late February 2024, in a fit of self-pity, Donald Trump described the numerous court cases he was forced to endure as “a form of Navalny.” It left one incredulous, of course, but with each new absurdity, we hoped that his popularity would finally reach a saturation point and that even his most fanatical supporters would finally have no other choice but to laugh him off the stage. Trump as a baby in diapers, Trump as an emaciated prisoner in a Siberian camp—we waited for the perfect meme to trigger the downfall of this humorless clown—because we knew that the next U.S. presidential election wasn’t all that far off, and that it would decide the future of democracy, women’s rights, health care, the cost of living, the rule of law, and the system of checks and balances that had kept the country from the brink of autocratic despotism for two and a half centuries.

When Trump’s first term in office finally came to a close, we managed to forget him for a while. And then we were faced with the prospect of experiencing exactly the same thing all over again. I began thinking more and more about his clownish presidency: the foul language, the smug misogyny, the grotesque logic of white supremacy, the erosion of dignity in the highest office of the country; the abuse of language in the media, the Oval Office, and in both houses of Congress. During its first few miraculous weeks, the Harris campaign adopted a strategy of mockery to take the wind out of Trump’s sails: instead of painting him as the single greatest danger to democracy, he and his brethren were reduced to the word “weird.” It worked for a while, and it threw him entirely off-guard—but it wasn’t enough, of course, and he bounced back with renewed ferocity.

Yet this new strategy of mockery opened my eyes to the fact that we’d feared him, and in doing so, we’d invested him with power. We need to understand the workings of psychological warfare, I thought; we need new paradigms. In the exhibition “Ridiculously Yours!,” artist Saâdane Afif created a tribute to French writer Alfred Jarry’s absurd play Ubu Roi from 1896, which was so controversial that it caused a scandal at its premiere and was promptly shut down. The play’s fame—and the fascination it holds even now, almost 130 years later—lies in the fact that its slap in the face of power still feels entirely timeless, still feels radical. In a parody of Macbeth, a revolutionary kills the King of Poland, crowns himself king, and then performs a series of obscene acts. Fat, infantile, vulgar, greedy, and cruel: Ubu Roi is an antihero whose relevance remains so enduring that the adjective “ubuesque” is still used in French political debates to this day. As a despot, King Ubu represents the abuse of power and authority; at the same time, he mirrors our own complicity, our own political sloth. We have allowed ourselves to be distracted, to get wrapped up in nonsense as words were eroded and lost their meaning. But when language itself is weaponized, we have to look to different means to arm ourselves. The danger Hannah Arendt warned about has been brewing for some time—that if you deliberately distort the truth long enough, and people can no longer distinguish between fact and fiction, they will eventually no longer care. And then you can do as you like with them—a spectacle we’ll be forced to witness over the next four years.

Daumier and Chaucer, Rabelais and Swift: over and over again, history has shown us the disarming power of satire and parody, lampoon and spoof. Since time immemorial, laughter has been used as a means of exposing hypocrisy, of making the powerful look small and ludicrous. But now that the radical right has adopted art’s most effective methods of undermining authority—embarrassing taste, bad behavior, rudeness, and a lack of shame—new strategies are required. The tools we need to make art dangerous again are waiting to be invented—and they’ll have to be cleverer, more sophisticated, and far more subversive than ever before.